Stabilizing Rural Safety Net Hospitals

This is the third edition of a Manatt Health series on safety net hospitals. To read the first issue on how safety net hospitals can benefit from the new Medicaid Access Rule, click here. For our second issue on innovative funding approaches, click here.

Key Points:

Rural communities face unique economic, population health and geographic needs that contribute to the numerous challenges that rural safety net providers face in delivering health care services sustainably.

Even though the rural population is continuing to grow, nearly a third of rural hospitals are vulnerable to closure.

Given the structural challenges and care shortages, it is increasingly important to develop programs, policies and resources to ensure Americans in rural communities have equitable access to care.

On November 20, Manatt Health will host a webinar on rural health strategies. Click here to register.

The Landscape of Providing Care in Rural Areas

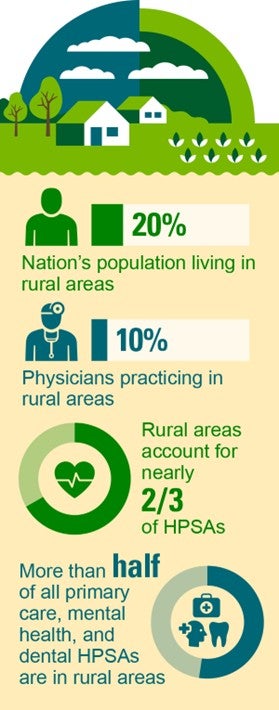

With more than 190 rural hospital closures and conversions between 2005 and 2023, access to care in rural communities is increasingly at risk. As of 2023, about 30% of all rural hospitals were vulnerable to closure.1, 2 Rural communities have unique economic, population health and geographic needs that contribute to the numerous challenges facing rural providers in delivering health care services sustainably.

Rural populations are both older and sicker than their urban counterparts and experience higher rates of chronic disease and behavioral health needs.3,4,5,6 The aging population in rural areas has resulted in an increased reliance on Medicare coverage, and economic conditions have yielded a disproportionate representation of Medicaid enrollees.7

Rural safety net hospitals are crucial for providing primary, urgent and specialty care in rural communities, where patients travel much farther for health services (23.9 miles versus 3.4 miles in urban areas), and specialty providers are scarce.8,9,10,11These hospitals operate on tight budgets, mainly funded by Medicare and Medicaid, which cover over half of their revenue but reimburse less than the cost of care.12 Given these structural challenges, it is increasingly important to develop programs, policies and resources to ensure Americans in rural communities have equitable access to quality care.

This brief considers new policy efforts aimed at mitigating both the causes and effects of these safety net hospital closures across rural America.

Existing State and Federal Policies to Support Rural Providers: Successes and Outstanding Challenges

Over the years, a patchwork of federal and state policies have been implemented to respond to the range of the challenges facing rural health care providers and the populations they serve.

Financial Supports. Federal efforts to address reimbursement levels have been somewhat successful in stemming the tide of rural hospital closures. The Critical Access Hospital (CAH) designation helped reduce financial vulnerability by providing a cost-based reimbursement system under Medicare, more flexible staffing requirements, access to resources (e.g., quality improvement programs, workforce training and technical assistance).13 The CAH reimbursement model coupled with the federal Rural Health Clinic (RHC) model for outpatient services is generally viewed as a sustainable reimbursement model.14 The Sole Community Hospital (SCH) also offers cost-based rate adjustments but has been less successful due to lack of updates in base rates.15 The Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) designation, created in 2020, provides an alternative designation to existing CAHs offering only emergency services, observation care and certain outpatient services at enhanced rates to recognize overhead costs.16 However, CAHs have shown limited interest in the REH opportunity due to inadequate financial incentives and 340B ineligibility.17

States have also dedicated resources to rural health facilities through various funding streams. California's legislature created a Distressed Hospital Loan Program, offering $150 million in zero-interest loans to eligible hospitals.18 New York provides supplemental Medicaid payments through its Vital Access Provider (VAP) and Vital Access Provider Assurance Program (VAPAP) to rural safety net hospitals.19 These programs target operating support for transformation initiatives that address financial viability, community service needs, quality of care and health equity.

Beyond dedicated state funding streams, several states have leveraged Medicaid supplemental payments for rural hospitals through disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments to cover uncompensated care costs and supplemental payments, which aim to fill the gap between fee-for-service Medicaid base payments and the (higher) amount that Medicare would have paid for those same services.20 For instance, Arizona's Rural Hospital Inpatient Fund, established in 2005, supplements rural inpatient payments.21 Arkansas used its Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration authority to create a “Rural Life360 HOME,” offering intense intervention and care coordination for rural residents, particularly those with serious mental illness or substance use disorder.22, 23

Efforts to Reform Reimbursement. While these policy solutions complement one another, siloed implementation results in piecemeal improvements failing to provide a path to long-term sustainability for resource-constrained hospitals. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has piloted projects to support rural providers and improve their finances. Notably, two state-specific models aim to help rural providers shift from volume- to value-driven payments:

Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, an all-payer global budget payment system; and

Vermont All-Payer ACO Model, which provides up-front funds for providers interested in participating in accountable care organizations.

CMMI is continuing to explore ways to support the rural safety net, including newly announced initiatives like:

The States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development model (the AHEAD model), including its methodology specifically targeting reimbursement for CAHs;24

The Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) model, which is targeted at improving maternal health for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees with particular focus on rural and other high-need areas;25 and

The Innovations in Behavioral Health (IBH) model, which—unlike several behavioral health‑focused payment models—permits Medicare participation, thereby promoting Medicare‑Medicaid alignment. This may be especially true in rural states in which public payers predominate.26, 27

Workforce Development. States play a crucial role in addressing workforce shortages through their control of licensure for medical professionals. Policy levers available to states include expanding the scopes of practice for advanced practice registered nurses and physician assistants and streamlining licensure processes.28 At the federal level, Congress added 1,000 new Medicare-supported graduate medical education (GME) slots, at least 10% of which are required to be located in a rural area.29

Despite these efforts, rural facilities' lower salaries and benefits, coupled with poorer working conditions, deter providers with significant debt from working in these areas. Some states use their public universities to address this challenge. For example, the University of California Programs in Medical Education (UC PRIME) aim to address provider shortages in underserved communities through specialized training and mentoring, focusing on specific underserved regions.30

Outstanding Challenges and What’s Next

Additional state and federal policymaking is essential to address the ongoing challenges for rural safety net providers. This would ideally entail a comprehensive assessment of the long-term sustainability of rural safety-net providers. Policy actions could include easing eligible hospitals’ ability to apply and be approved for CAH status and rebasing the calculation of payments for SCHs, Medicare-dependent hospitals and low-volume hospitals would allow a more up-to-date calculation (and associated reimbursement) of providing care in rural areas.31

The table below outlines some potential remedies that could be implemented at the federal and state levels to address urgently-needed reforms in the near-term. In addition, the table lifts up potentially scalable models and examples. Notably, community and provider support is essential to garnering momentum to enact these changes.

Policy | Potential Actor | |

|---|---|---|

Federal | State | |

Utilize Medicaid supplemental payments | Medicaid authority permits the use of state directed payments for targeted investments in rural hospitals. | Utilize supplemental payments that direct funding to rural hospitals and providers Examples: Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System’s Rural Hospital Inpatient Fund, a supplemental payment authorized by the legislature in 2005. New York directed payment program for CAHs32 and SCHs (Sole Community Hospitals)33 Texas’ inpatient hospital directed payment program that includes “rural hospitals” as qualifying for directed payments |

Provide support for dedicated GME and training funds for rural areas. | Additional dedicated GME slots for rural areas and/or a medical version of Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). | 1115 waivers for loan forgiveness and provider training Examples: Massachusetts is investing $43.24M in loan repayment for safety net providers. New York is investing $649M in programs like Career Pathways Training and loan forgiveness. |

Implement parity in telehealth reimbursement | Federal legislation based on the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) could require parity in reimbursement between services delivered in-person and via telehealth. | Waiver authority can be leveraged to enhance payment for telehealth, including through 1135 waivers, allowing Medicare to pay for office, hospital and other visits via telehealth (some of these changes are permanent and others are set to expire on December 31, 2024). |

Provide additional resources for infrastructure (e.g., brick and mortar, equipment, staff compensation) | The Rural Hospital Stabilization Act (H.R. 8245) would establish a Hospital Stabilization Pilot Program to provide $20 million annually in grant funding to hospitals, CAHs and REHs for minor renovations, staff training, equipment acquisition and recruiting or hiring new staff. This, or a comparable proposal, would ensure additional dedicated resources for expenses required to provide care but often not reimbursable. | State legislatures to take a similar approach to the federal proposal by dedicating additional resources. Examples: The Wisconsin launched the Healthcare Infrastructure Capital Grant Program in 2021 for over $100M in infrastructure investments. Texas implemented a Rural Hospital Broadband Infrastructure Program, to improve connectivity in rural health care settings. |

Reassess federal co-location policies | CMS could explore additional flexibilities to Medicare conditions of participation (CoPs) to enable co-location of services, including behavioral home health, mental health, hospice and emergency transportation. Example: Cannon Memorial Hospital in NC became the first CAH to co-locate with a behavioral health hospital after seeking an exemption from CMS to address unprecedented behavioral health needs | n/a |

Continued advocacy and policymaking at the federal and state level is critical to build on existing polices and models that have proven successful for rural providers and to address the ongoing equity challenges in rural health care. Further innovation to ensure equitable access to health care services in rural American communities and reverse the recent trend of rural hospital closures remains critically important.

1 Rural Hospital Closures. UNC Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. 2024. Available here. 2 The Crisis in Rural Health Care. Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform. Available here. 3 Medicaid and Rural Health. MACPAC. April 2021. Available here. 4 Advancing Rural Health Equity: Fiscal Year 2022 Year in Review. CMS. November 2022. Available here. 5 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. November 13, 2023. Available here. 6 Morales, D.A., Barksdale, C.L., and Beckel-Mitchener, A.C. A call to action to address rural mental health disparities. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. October 2020. Available here. 7 An estimated 18% of adults and 47% of children are covered by Medicaid in small towns and rural areas, compared to 15% and 40% in metro areas. MACPAC | Medicaid and Rural Health, 2021. 8 Why Health Care Is Harder to Access in Rural America. U.S. Government Accountability Office. May 16, 2023. Available here. 9 Rural Health Strategy. CMS. Available here. 10 Rural Health Snapshot (2017). NC Rural Health Research Program. May 2017. Available here. 11 Jaret, P. Attracting the next generation of physicians to rural medicine. AAMC. February 3, 2020. Available here. 12 AHA | Rural Report, 2019 13 In order to qualify for the CAH designation, hospitals must have 25 or fewer acute care inpatient beds, be located within 35 miles from another hospital, maintain an average length of stay of 96 hours or less for acute care patients, and provide 24/7 access to emergency care services. There are currently more than 1,300 CAHs across the country. For more on the CAH designation, see the CMS information page here. 14 Rural Health Clinic: Fact Sheet. CMS. June 2007. Available here. 15See 42 CFR § 412.92. 16 Rural Emergency Hospitals. CMS. September 2024. Available here. 17 Kacik, A. For many rural hospitals, new payment model doesn’t add up. Modern Healthcare. January 16, 2023. Available here. 18 Distressed Hospital Loan Program. California Department of Health Care Access and Information. Available here. 19 Hospital Vital Access Provider Assurance Program (Hospital VAPAP). New York State Department of Health. December 2023. Available here. 20 Rural Hospitals and Medicaid Payment Policy. MACPAC. August 2018. Available here. 21 Rural Hospital Inpatient Fund Payments. Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. 2024. Available here. 22 Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me (ARHOME). Medicaid.gov. Available here. 23 Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State. Kaiser Family Foundation. September 10, 2024. Available here. 24 Stowe, E.C., Yoder, R., and Karl, A.O. Understanding CMS’ AHEAD Model: Medicare Hospital Global Budget Design and Implications. Manatt Health Highlights. March 28, 2024. Available here. 25 Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) Model. CMS. 2024. Available here. 26 Innovation in Behavioral Health (IBH) Model. CMS. 2024. Available here. 27 Lipson, M., Johnson, T., and Barnard, Z. CMMI’s Innovation in Behavioral Health: Promoting Physical and Mental Well-being. Manatt Health Highlights. April 24, 2024. Available here. 28 Rural Healthcare Workforce. Rural Health Information Hub. August 15, 2024. Available here. 29 See Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, P.L. 116-120 (2020). 30 Programs in Medical Education (PRIME). University of California Health. Available here. 30 See, for example, the Rural Hospital Support Act (S. 1110). Available here. 32 Approved State Directed Payment Preprints. ID:155636. Medicaid.gov. Available here. 33 Id.