State Benchmarking Models: Promising Practices to Understand and Address Health Care Cost Growth

Editor’s Note: As states grow increasingly concerned with rising health care costs, establishing health care cost growth benchmarking programs can provide a structure and process for increasing health system transparency and developing strategies for containing costs. In a new white paper prepared for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Manatt Health explores the evolution of cost growth benchmarking programs across a growing list of states. The white paper, summarized below, presents the history of benchmarking programs, shares the five common features of benchmarking programs, provides emerging use cases and highlights opportunities for standardization. Click here to download the full white paper—and here to view our recent webinar with practical guidance, best practices and key lessons from state innovators on how to build an effective cost growth target program.

History of Cost Growth Benchmarking Programs

At least eight states have adopted health care cost growth benchmarking programs—five in the past two years—that bring stakeholders together to set cost growth targets for health care spending, collect data from payers to measure progress, and identify where policy or program action may be required. In 2012, Massachusetts became the first state to enact a cost growth benchmarking program, passing legislation that created a statewide infrastructure. The Massachusetts program remains the nation’s most expansive cost growth benchmarking program, with an annual reporting and hearing process that engages stakeholders across the state’s health care system to inform and shape potential policy interventions.

The next two states to adopt cost growth benchmarking programs were Delaware and Rhode Island, which adopted streamlined programs by executive orders (EOs) in 2018 and 2019, respectively. In 2019, Oregon, which had previously extended its long-standing Medicaid cost growth target to cover state employees and teachers, enacted SB 889 to create a cost growth benchmarking program to cover all state health care spending. In 2020 and 2021, four more states—Connecticut (2020), Washington (2020), New Jersey (2021) and Nevada1 (2021)—joined Oregon, taking initial steps to establish state cost growth benchmarking programs.2 While these five state programs are at varying stages of implementation, all have committed to an inclusive stakeholder process for providers, insurers, employers and consumer interests to set a cost growth target and allocate the resources necessary to address cost growth drivers and make health care costs more affordable and sustainable.

Common Features of Benchmarking Programs

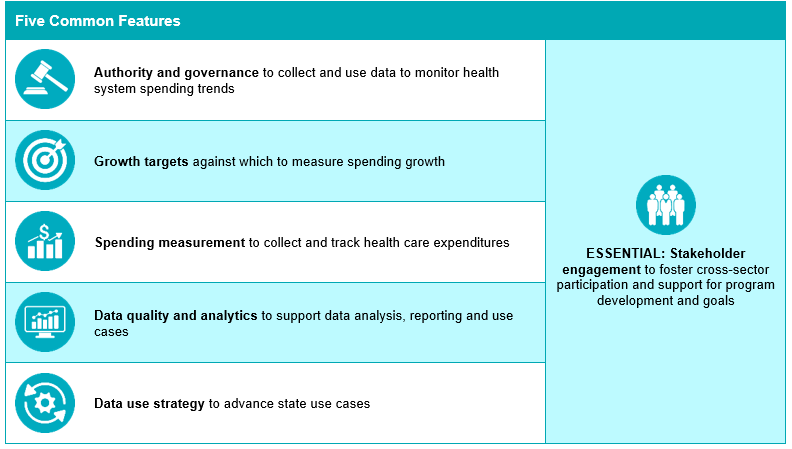

State cost growth benchmarking programs share several common features, including (1) authority and governance, (2) growth targets, (3) spending measurement, (4) data quality and analytics, and (5) data use strategy, all of which are supported by and critical to meaningful stakeholder engagement.

Emerging Use Cases in Benchmarking Programs

States have tailored their benchmarking programs to pursue a broad range of use cases that reflect local priorities for expanding transparency, addressing cost drivers and ensuring that health care spending is directed to the most beneficial and cost-effective services. States may use cost growth benchmarking programs to support and reinforce existing cost-containment and transparency initiatives, providing a new mechanism to collect data and convene stakeholders around common goals. In this section, we look at four leading use cases:

- Improving health care cost transparency

- Investing in primary care

- Identifying trends in patient cost-sharing

- Advancing Alternative Payment Methods (APMs)

1. Improving Health Care Cost Transparency

The Issue: Health care spending for an average American was six times greater in 2019 than it was in 1970.3 Health care spending growth has consistently outpaced gross domestic product (GDP) growth, with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services projecting expenditures to reach $6 trillion and comprise nearly 20% of our GDP by 2027.4 Understanding the contributors to health care cost growth is essential to developing comprehensive and cohesive strategies to contain it.

How Benchmarking Helps: Cost growth benchmarking programs allow states to collect comprehensive data about the performance of their health care systems, providing stakeholders with crucial information about their market’s health care cost centers and cost drivers. Benchmarking programs also provide recurring opportunities—as health care cost growth assessments are released—to convene stakeholders around results to provide additional context and to begin developing actionable policy and program interventions.

What States Have Done: Massachusetts supports an annual cycle of data reporting and public hearings in which payers, providers and hospital leaders discuss performance, key trends, identified cost drivers and strategies to improve system performance.

2. Investing in Primary Care

The Issue: States are increasingly seeking to ensure health system spending is being invested in services and activities that support long-term health, including primary care. Higher investments in primary care are linked to improved patient health, including decreases in emergency department visits, fewer patient hospitalizations and long-term cost reductions.5

How Benchmarking Helps: Benchmarking programs provide states with a mechanism to measure and monitor primary care spending against total system spend and use this information to influence market redistribution of funds to increase these important, preventive investments.

What States Have Done: In 2020, Connecticut’s Governor Lamont issued EO No. 5, which charged the OHS with developing and recommending a primary care spending target for the state beginning in 2021 in order to reach a primary care spending target as a percentage of THCE of 10% by 2025.

3. Identifying Trends in Patient Cost-Sharing

The Issue: Consumers are increasingly bearing the burden of health care system cost growth with rising premium contributions and out-of-pocket expenses. Nationally, from 2008 to 2018, the average premiums for families with employer health coverage increased by 55% and average out-of-pocket spending increased 70%, as health plans frequently cost more to cover less.

How Benchmarking Helps: States can build on their benchmarking programs’ data collection processes to collect “supplemental” data on consumer premiums, cost-sharing and plan design to better understand how consumer spending and spending liability for health care services are changing over time.

What States Have Done: Massachusetts collects supplemental data on changes in consumer premiums, cost-sharing and plan types as part of its annual reporting process. This data provides critical context to the state’s overall benchmarking findings.

4. Advancing Alternative Payment Methods (APMs)

The Issue: The health care industry is increasingly moving away from traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payments, which encourage more services rather than high-value and well-coordinated services. Both public and commercial payers are experimenting with multiple APMs, which encourage plans and providers to align and share accountability—through various forms of risk-sharing—for achieving the Triple Aim (access, quality and cost of care) for a defined or attributed population.

How Benchmarking Helps: A cost growth benchmarking program can collect information on the number of lives covered under APMs, including definitions of how each model shares risk between payers and providers for both up- and downside risk. As APMs evolve from relatively narrow performance incentives to broad capitation payments, benchmarking programs can help facilitate common understanding between payers and providers on how progress will be measured and what reasonable goals are.

What States Have Done: Oregon has made a major commitment to expanding APMs and intends to use its benchmarking program to track progress and facilitate collaboration between payers and providers necessary to achieve its ambitious goals. The state has invested heavily in expanding APMs or value-based purchasing (VBP) within its Medicaid program since 2012, and it views that work as central to the state having saved $6.5 billion over ten years (2012–2022).6

Broadening and Deepening the Focus of Benchmarking Programs

As states consider the broad range of factors that impact cost growth trends, benchmarking programs will similarly evolve to address new use cases and view old use cases in new ways. In many states, efforts to restrain hospital costs and prescription drug prices predate benchmarking programs, and states may decide to more closely link these initiatives to benchmarking programs as benchmarking evolves. In the meantime, policymakers already are linking benchmarking programs to a wide range of cost-related initiatives.

- Provider Consolidation. Provider consolidation, especially vertical integration into health systems, has increased in recent years,7 driving states’ interest in understanding the effects of these changes on their health care systems and consumers. Benchmarking programs can provide important information to inform provider consolidation discussions and may be enhanced to include supplemental reporting requirements such as advance notice of proposed large provider mergers, acquisitions and changes in ownership.

- Accounting for Geographic Variation. As larger, more geographically diverse states establish cost growth benchmarking programs—such as Oregon, Pennsylvania and California—there will be a greater need to consider regional differences in populations and markets in assessing cost growth trends.

- Advancing Health Equity. States are increasingly exploring how benchmarking programs may be used to advance health equity priorities, including assessing how health care spending may be inequitably distributed by community and population type and whether consumer cost and cost liability may present a disproportionate barrier for some populations more than others.

- Ensuring Workforce Stability. One concern about state benchmarking programs is that providers, in an effort to reduce costs, will cut necessary and critical members of their workforces responsible for delivering high-quality care. Oregon recognized this concern and is planning to monitor the market for unintended workforce consequences of the benchmark. California’s benchmarking bill similarly includes protective language.

How Standardization Could Benefit Benchmarking Programs

Two trends suggest now is the time to consider how standardization could support the continued growth and utility of state benchmarking programs:

- Program Proliferation. Massachusetts established the first benchmarking program in 2012, and it continues to serve as the model for new states’ programs, though replication was slow to occur. No state had followed Massachusetts in establishing a benchmarking program until Delaware (2018) and Rhode Island (2019) did so by EO. Since then, however, progress has been rapid.

- Common Features. All eight states that have state benchmarking programs share a common set of key features, as seen in Figure 1. The Peterson-Milbank Program for Sustainable Health Care Costs has organically facilitated a level of standardization through the procurement of one vendor to support the establishment of the five newest state programs, with the vendor working with the states to tailor the baseline Massachusetts model to address local needs and priorities. Increased standardization of benchmarking program designs would allow for more consistent data collection and effective data use across states.

Conclusion

With eight states on board and others looking closely at cost growth benchmarking, these programs are destined to become a critical data resource for states seeking to understand health care cost growth trends and what can be done to contain costs and direct spending toward efficient and equitable investments. Cost growth benchmarking programs are certainly not a panacea; the hard work of controlling costs in a health care system that has grown faster than inflation for decades will require states to overcome entrenched interests and make difficult choices. What benchmarking can do is help states identify cost drivers and make data-driven decisions with the full spectrum of stakeholders at the table.

1 Nevada actually passed authorizing legislation in 2019, but the program was not operative until Governor Sisolak used his broad authority under the bill to start a benchmarking program in 2021.

2 “Five States Join the Peterson-Milbank Program for Sustainable Health Care Costs,” Milbank Memorial Fund. March 9, 2021. Available here: https://www.milbank.org/news/five-states-join-the-peterson-milbank-program-for-sustainable-health-care-costs/.

5 “Investing in Primary Care: A State-Level Analysis,” Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC) 2019 Evidence Report. July 17, 2019. Available here: https://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/resources/pcmh_evidence_report_2019_0.pdf.

6 This estimate excludes high-cost prescription drugs. “1115 Waiver Renewal Submission,” Oregon Health Authority. July 27, 2016. Available here: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HSD/Medicaid-Policy/Documents/Waiver-Renewal-Submission.pdf.

7 According to a 2019 study by researchers from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the share of physicians affiliated with a health system increased by 11 percentage points from 2016 (40%) to 2018 (51%), and this impact was particularly prevalent among primary care physicians. Health Affairs, August 2020. Available here: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00017#:~:text=The-consolidation-of-physicians-into,substantially-from-2016-to-2018.&text=The-share-of-hospitals-affiliated,70-percent-to-72-percent.