Preparing a Community Health and Health Equity Strategic Plan

Objective

Academic health systems serve a vital role in the health and well-being of the communities they serve. They employ thousands of people and are an economic engine delivering clinical care, the training of health care professionals, and the conduct of innovative research. They also make direct investments in community programming aimed at improving health and forge innovative partnerships with community organizations and other health systems to tackle pressing community health challenges.

The Affordable Care Act recognized the role of providers in advancing community health, mandating that nonprofit hospital organizations conduct community health needs assessments (CHNAs) every three years and develop a community health improvement plan (CHIP) to meet identified needs. While the CHNA and CHIP processes prompt academic health systems to recognize and address community needs, some health leaders recognize that a more rigorous system-wide planning process is required to effectively allocate resources, drive tangible reductions in health disparities, and improve access to care. Evolving population health management capabilities and strategically targeted health interventions have enabled forward-thinking academic health systems to improve community health. This note describes how to prepare a multi-mission community health and health equity strategic plan.

|

Tip: Ensure early alignment on key terminology to appropriately scope and shape strategic recommendations. Tip: Clearly distinguish direct investments in community health improvement from unrecovered costs of serving Medicaid beneficiaries and embedded subsidies for research and education. Tip: The IRS-defined community benefit does not count significant programming and investment made by many academic health systems to improve community health. |

What is Community Health and Health Equity Activity?

Nonprofit health systems are required to report community benefit activities to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as part of their tax-exempt requirements. These include dollars spent to cover what is often considered the cost of doing business as an academic health system, including education, research, Medicaid shortfall, and charity care. Community benefit activities also include more active, direct investment in community health and wellness activities, including screening programs and health fairs. More recently, several academic health systems have also been pressing forward with significant investments to ameliorate homelessness (by partnering to build affordable housing), improve food security, improve access with mobile units, and partner with schools on mental health initiatives, among others.

Preparing a Health Equity Strategic Plan

To build a community health and health equity strategy, academic health systems must:

- Develop a vision for community benefit by connecting and engaging community leaders.

- Design the community program and investment portfolio.

- Implement a community health and health equity organizational model.

- Establish clear success metrics and goals to track progress and drive decision-making.

- Ensure financial sustainability of community health and health equity investments.

- Measure progress along an “equity continuum” over time.

Successful strategic planning and implementation require robust engagement and participation of health system leaders and community members. Leaders should build on the progress and connections made through the CHNA and CHIP processes, sharpening the health system’s ability to deploy health improvement interventions in pursuit of a shared vision and clearly defined priorities.

1. Develop a Vision for Community Benefit by Connecting and Engaging Community Leaders

Connect with the Community

|

Tip: Be open and honest when sharing community stakeholder feedback with leadership. It is critical to triage and enhance community outreach and partnerships. |

The dictum “know thyself” applies here. A thoughtful look in the mirror is a necessary first step in developing a vision, which will be meaningfully informed by interviewing leaders of community organizations and local health departments to understand opportunities for further partnership and engagement. Appreciating community health priorities and ensuring the “community voice” is present in all deliberations is a hallmark of the leading health equity programs. In most instances, the interviews will confirm that there are significant unmet needs that align with the health system’s strategic priorities. Bringing to bear academic health system resources—the clinical network, program portfolio, research program, and population health capabilities—can result in significant improvements to community health outcomes if interventions are designed and implemented in partnership with community organizations. However, most academic health systems have insufficiently coordinated community health programming, often creating siloes across multiple operating units, missions (clinical, research, academic), hospitals, and ambulatory locations. To prove most effective, community programming must be systemically aligned with clear priorities and actionable data for making decisions, directing investments, focusing efforts, and holding leadership accountable. Furthermore, many communities and their leaders distrust academic health systems, due primarily to inconsistent investments and lack of meaningful partnerships. Community leaders frequently desire more regular engagement with health system leaders and clearer, more direct communication about decisions regarding community engagement and investment.

Establish the Vision

A systemwide vision for community health and health equity will go a long way to cementing the commitment of leadership. One Manatt Health client recently built this vision statement:

“Partner with our communities to provide excellent, compassionate care and ensure everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health.”

To ensure the vision spoke to all stakeholders, this client used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s definition of health equity (“everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health”). This academic health system also committed itself to:

- Establishing trust.

- Embedding the pursuit of health equity as a core value.

- Elevating and incorporating the voice of the community.

- Investing resources in ways that have tangible and measurable impact on community health outcomes and disparities.

- Serving as an anchor institution.

2. Design the Community Program and Investment Portfolio

Construct a Balanced Portfolio Around System Priorities

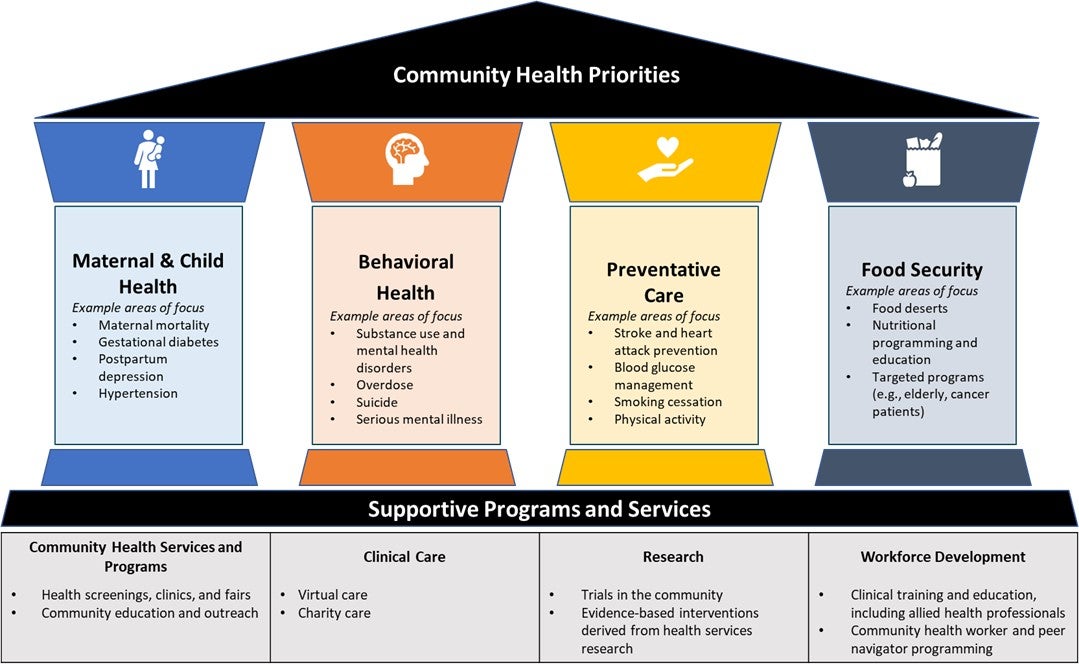

Each academic health system must determine priorities. Consider the following example portfolio, which illustrates both focus and balance:

Illustrative Community Health Equity Program Portfolio

A well-constructed portfolio serves to specify priorities and to organize and harness system-level resources in a forceful and intentional manner. It should have the following features:

- A focused and limited set of system-wide community health and health equity priorities toward which investments and programming will be oriented to maximize potential for impact.

- A portfolio management model that considers programming and investments through a structured decision process and with consistent evaluation criteria.

- Impact that goes beyond the IRS-defined “community benefit” calculations to tangible measures of community health and health equity goals and metrics with regular reporting and monitoring to leadership and the public.

- Organizational structure and processes accountable for connecting system resources to regional and mission-based programming and clear leadership accountability for results.

Academic health systems must also balance the proportion of indirect versus active investment in community health and health equity. Some health systems spend most of their community benefit dollars on Medicaid shortfall and subsidies for education, research, and charity care while directing a fraction on net new investment in community-facing activities, such as vaccination clinics, chronic disease awareness and education programs, sponsorship of community organizations and events, patient transportation programs, housing, and mobile health screenings. While the level of direct community investment is limited by the rising cost of care of Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries and plateauing commercial reimbursements, the right investments can nevertheless make a substantial positive impact on community trust, health outcomes, and health equity.

Define Signature Initiatives

Academic health systems do well to define signature initiatives for community health engagement and improvement. Signature initiatives are vehicles for concentrating limited resources on the highest-impact initiatives that have the potential to move the needle on community health outcomes. They are also useful focal points for philanthropic campaigns and other external funding opportunities including foundation and research grant funding. External funders are more likely to support evidence-based programs and their institutions that have demonstrated success over a long period of time at scale. Examples of signature initiatives developed by Manatt Health clients include:

|

Example Signature Initiative: The University Hospitals Rainbow Ahuja Center for Women & Children offers a 40,000 sq. ft. one-stop shop for clinical and social support services for women and children, including integrated behavioral health services, dental, vision, nutrition education, and a Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) office. |

- An integrated maternal and child health program that deploys a model of integrated clinical and social support in a comprehensive facility model located in an underserved area.

- Behavioral “health hubs” deployed in areas of community need.

- Expanded mobile community health programs that also provide access to clinical trials.

- School-based partnerships to expand access to social, behavioral, and clinical care for adolescents.

- New community partnerships to expand food service delivery to vulnerable patients (e.g., medically tailored meals for cancer patients).

- Pipeline programs sponsored by the academic health system and driven by community colleges, high schools, and other community organizations to support a diverse workforce that reflects the community served.

3. Implement a Community Health and Health Equity Organizational Model

A distinguishing feature of leaders deeply engaged in improving disparities is the “all-in” nature of their commitment as an academic health system. Practically, this means that every aspect of the health system is engaged in this endeavor and in realizing the health equity vision.

|

Operating Units and Functions |

Roles in Advancing Community Health and Health Equity |

|

|

Clinical Operations |

|

|

|

Research |

|

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

Community Engagement |

|

|

|

Population Health |

|

|

|

Quality and Patient Safety |

|

|

|

Human Resources |

|

|

4. Ensure Financial Sustainability of Community Health and Health Equity Investments

As the cost of care continues to rise across the nation, many academic health systems are struggling to realize their financial targets and are reluctant to make significant new investments in community programming. However, there are several principles that health systems can employ to maximize financial sustainability with these investments.

- Manage investment impact of all community health programming. Multi-hospital health systems will often have fragmented community programming, resulting in investments being “spread too thin” and limiting their impact.

- Track financial return on community health programming. Community health programs are common entry points for new patients and referrals. To better track how they contribute to the financial performance of the health system, health systems should track patient origin data, downstream referrals, and cost savings from preventative services. For example, if a mobile mammography unit directed 20 patients to the health system, generating multiple breast cancer diagnoses, procedures, and follow-up visits, the mobile mammography program should be credited for that incremental volume and revenue.

- Reinvest some portion of revenue or savings from community health programming. These funds could be reinvested into the community health and health equity strategy. Using the example of the mobile mammography unit described above, some portion of the incremental revenue generated could be reinvested into scaling the program.

- Align philanthropic and external funding activities with system priorities. Aligning philanthropic and external funds would maximize the health system’s impact on community health outcomes. For example, philanthropic campaigns may be focused on securing long-term funding for signature initiatives with detailed and sustainable operational plans (e.g., naming opportunity for an integrated maternal and child health center). Health systems may also coordinate with their researchers to pursue large research grants linked to system priorities.

- Develop and deploy state advocacy and payer strategies. New strategies will help to support community health programming. For example, health systems in North Carolina may take advantage of the Healthy Opportunities Pilots, which reimburse various services aimed at addressing social determinants of health for Medicaid managed care beneficiaries. Additionally, health systems may be able to leverage population health data and progress made on community health outcomes to participate in or enhance existing value-based arrangements and Medicaid directed payment programs.

5. Establish Clear Success Metrics and Goals to Track Progress and Drive Decision-making

Academic health systems must be able to define what it means to achieve their vision for community health and health equity. To do so, each priority area in their community health intervention portfolio must be assigned meaningful success metrics and achievable goals. For example, one Manatt Health client prioritized maternal and child health and wished to improve maternal mortality and morbidity rates in their community. The goals were benchmarked against publicly available data sources and agreed on by leadership.

Sample Success Metrics and Goals for Maternal and Child Health

| Metric | Goal | Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

|

% of pre-term births without medical indication |

≤8% | 10% |

|

Rate of maternal mortality |

≤15 per 100,000 live births |

24 per 100,000 live births |

|

Rate of severe maternal morbidity |

≤70 per 10,000 deliveries |

72 per 10,000 deliveries |

Ideally, the data required to track progress against defined goals are easily extractable with minimal manipulation from their respective databases and linked to an automated dashboard or scorecard. Access to real-time data is critical for meaningful and timely decision-making. In some cases, health systems will need to bolster their data capabilities to validate data or capture new data elements.

6. Measure Progress Along an “Equity Continuum” Over Time

As with any strategic plan, there is always a risk of early momentum giving way to competing resource demands or shifting priorities over time. Health disparities have evolved over decades; they will not be eliminated immediately. It will take years of dedicated efforts and a commitment to continue the journey towards a just and equitable health system over the long term. To maintain institutional will over a long period of time, the health systems must establish waypoints that can be used to demonstrate progress and maintain accountability for advancing a community health and health equity strategy. A useful model for long-term navigation is a maturity model derived through a combination of observing organizations at various stages of progress and the articulation of an aspirational endgame. One version of such a maturity model is shown below. This maturity model can be modified depending on individual context.

Sample Maturity Model for Community Health and Health Equity

With heightened public and regulatory scrutiny on health disparities, providers are under mounting internal and external pressure to deploy resources and partner with their communities to advance health equity. Some are just beginning to conceptualize their role in the community whereas others are seeking ways to enhance their impact. Where an organization is along that continuum is less important than their commitment. We hope that this note serves as an actionable guide for academic health system leaders who are committed to investing in health equity. We extend our gratitude to our visionary clients whose dedication has advanced health equity across the nation.

Appendix. Lessons Learned from Literature and Peer Organizations for Developing an Effective Community Health and Health Equity Strategy

Sources

American Hospital Association Institute for Diversity and Health Equity. (n.d.). The Health Equity Roadmap. https://equity.aha.org/

Anthony, S., Boozang, P., Carrington, E., & Torres, Bryant. (2023, December 13). Achieving a Racially and Ethnically Equitable Health Care Delivery System in Massachusetts: A Vision and Proposed Action Plan. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation. https://www.bluecrossmafoundation.org/sites/g/files/csphws2101/files/2023-12/Health_Equity_Report_Dec23_FINAL.pdf.

Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Health Justice. (n.d.). Who We Are and What We Do. https://www.aamchealthjustice.org/

Boston Medical Center. (n.d.). Health Equity Accelerator. https://www.bmc.org/health-equity-accelerator.

Cedars-Sinai. (n.d.). Community Benefit Program. https://www.cedars-sinai.org/community.html

Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. (2011, June). Principles of Community Engagement. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf

Newman, N., Elam, L., Kirch, D., Lam, A., Reginal, A., & Singh, A. (2021, July). On the Path to Health Justice: Opportunities for Academic Medicine to Accelerate the Equitable Health System of the Future. Manatt. https://www.manatt.com/Manatt/media/Documents/Articles/AMC-Health-Equity-Paper,-Framework-and-Case-Studies-July-2021_c.pdf.

Ohio Department of Health. (2020). Severe Maternal Morbidity and Racial Disparities in Ohio, 2016-2019. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/0657b23a-baba-4a74-b31c-25e216728849/PAMR+SMM+Final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-0657b23a-baba-4a74-b31c-25e216728849-nIngvj2

Ohio Department of Health. (2022). A Report on Pregnancy-Related Deaths in Ohio 2017-2018. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/960f9320-f4bc-4752-b6cb-990be663a31a/A+Report+on+Pregnancy-Related+Deaths+in+Ohio+2017-2018.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_79GCH8013HMOA06A2E16IV2082-960f9320-f4bc-4752-b6cb-990be663a31a-oG4C2Up

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. (2016). Public Health 3.0: A Call to Action to Create a 21st Century Public Health Infrastructure. The National Association of County and City Health Officials. https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf.

RUSH. (n.d.). RUSH BMO Institute for Health Equity. https://www.rush.edu/about-us/about-our-system.

Torres, B. & Lazarus, E. (2023, December 13). Health Equity Action Plan Toolkit. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation. https://www.bluecrossmafoundation.org/sites/g/files/csphws2101/files/2023-12/Health_Equity_Toolkit_Dec23_FINAL.pdf.

University Hospitals. (n.d.). UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Ahuja Center for Women & Children. https://www.uhhospitals.org/locations/uh-rainbow-center-for-women-and-children

Wyatt, R., Laderman, M., Botwinick, L., Mate, K., & Whittington, J. (2016). Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. https://www.ihi.org/resources/white-papers/achieving-health-equity-guide-health-care-organizations.