Mapping the Healthcare M&A Landscape Under the New Administration

- Mapping the Healthcare M&A Landscape Under the New Administration

- PAC Networks: Surging Growth Optimizes Patient Care Across Settings

- CMS Issues Rules to Help Stabilize Health Insurance Market

- New Webinar: HIPAA and Emerging Technologies

- The Goldilocks Theory of Bringing Change to the FDA

- Proposed 2018 Uncompensated Care Payment Methodology—Implications for Hospitals

- Insurer Merger Saga Ends Without Guidance on Efficiency Claims

- New Act Allows Creation of Federally Regulated Association Health Plans

Mapping the Healthcare M&A Landscape Under the New Administration

By Joel Ario, Managing Director, Manatt Health | Lisl Dunlop, Partner, Co-Chair, Antitrust and Competition | Tom Leary, Partner, Corporate and Finance | Eric Newsom, Partner, Co-Chair, Corporate and Finance

Editor’s Note: The healthcare M&A market continues to be among the most active sectors. In a recent webinar, Manatt examined how the policies and goals of the new administration are likely to impact healthcare M&A trends…how changes in the regulatory landscape are likely to affect M&A across all healthcare segments…and what to expect in terms of antitrust regulation and enforcement. The article below summarizes key points from the program’s M&A market overview. To download a free copy of the webinar presentation, click here.

_____________________________________________

Healthcare M&A Transactions—Deal Volume and Value

Healthcare M&A deal volume has been robust over the past five years and shows few signs of slowing down. Activity peaked in 2015—the year of the megadeal, particularly in the managed care and pharmaceutical arenas—with almost 1,100 deals approaching $100 billion in aggregate value.

In 2016, there remained a healthy level of activity with 939 healthcare industry deals valued at an aggregate of $71.7 billion. The most active sectors in 2016 included long-term care, hospitals, physician practices, healthcare IT, labs and other outpatient services (such as dialysis). Activity also increased in the rehabilitation, home healthcare and behavioral care segments. In contrast, activity levels declined in the managed care segment, in part because most of the major participants, including Aetna, Humana, Anthem and Cigna, were working through their then-pending deals that had been announced in the previous years. Sector transaction multiples declined slightly, with skilled nursing, assisted living and other facilities feeling reimbursement rate pressures seeing the most significant drops.

In Q1 2017, there were 239 announced deals in the healthcare industry, on par with the 240 deals that were announced in Q1 2016. The trends for 2017 year-to-date are similar to those seen in 2016. Long-term care, healthcare IT, physician practices and hospitals are comprising the bulk of activity thus far, while activity in the managed care and pharmaceutical spaces is more modest—although that could change quickly as the market begins to react to the recent terminations of the Anthem/Cigna and Aetna/Humana deals.

Drivers of the Robust Healthcare M&A Market

There are a number of drivers behind the robust healthcare M&A market, including macroeconomic factors such as a reviving economy, relatively low interest rates (at least for now), and available cash reserves for strategics, private equity and other potential buyers. In addition, the following trends stemming from the Affordable Care Act (ACA), repeal and replace efforts, and other market dynamics continue to influence the pace of healthcare M&A activity:

- Coverage expansion, leading to the potential for providers and managed care organizations to increase revenues and cash flows, as well as the need for providers to develop additional capacity and capabilities to handle the influx.

- Continued consolidation, resulting in increased negotiating leverage between payers and providers to achieve cost savings.

- The shift from the fee-for-service model to population health management, driving novel strategic relationships, new business models and an increased emphasis on consumerism.

Other key drivers in the current marketplace include:

- Hospitals and health systems seeking to build or expand integrated delivery systems with enhanced technology, clinical protocols and contracting leverage.

- Investment in innovation and technology becoming increasingly critical to functioning effectively in the new healthcare delivery model.

- Pharmaceutical companies shifting from in-house R&D to M&A strategies.

- Private equity (PE) activity in the healthcare space continuing to increase, particularly in healthcare services (i.e., long-term care, rehabilitation and behavioral health), digital health, and medical devices and pharma.

Healthcare Antitrust Enforcement in a New Administration

There were very few pre-election positions taken on healthcare antitrust enforcement—and since the election, there haven’t been many clues about how important antitrust enforcement, let alone healthcare antitrust enforcement, is to this administration. The new administration has been slow to appoint agency leadership. Makan Delrahim, nominated to be the “top cop” for antitrust at the Department of Justice (DOJ), had his confirmation hearing postponed due to a paperwork snafu. Therefore, for now, the DOJ Antitrust Division is operating without permanent leadership. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) also has not seen much appointment activity. The Commission is now operating with only two out of five commissioners.

In spite of the lag in appointments, healthcare antitrust enforcement is likely to continue in force. There has been a history of bipartisan support for strong antitrust enforcement in healthcare, and the agencies over the last eight years have established a strong track record in prosecuting anticompetitive conduct in healthcare.

In addition, there’s a large and growing body of economic analysis raising concerns about consolidation and its effect on pricing, quality and other metrics. Most studies indicate that the growth of market power in various segments of the healthcare economy is not helping to keep costs down, which is ultimately what everybody wants. The administration continues to be concerned with healthcare cost issues, and acting FTC Chair Maureen Ohlhausen already has said that healthcare and pharma will remain strong focus areas.

Provider Merger Antitrust Enforcement

Hospital mergers are the province of the FTC, which has achieved nine straight wins since 2008. Two recent appellate decisions have confirmed the FTC’s approach to market definition, including the presumption of anticompetitive harm at high levels of concentration. In addition, the courts have remained skeptical of efficiency justifications, not accepting claims that hospitals and physician groups need consolidations to develop the scale to invest or create a continuum of care. There also are concerns that any savings won’t be passed on to insurers.

The states often play a supporting role in provider merger antitrust enforcement. Examples include Idaho in St. Luke’s, Pennsylvania in Hershey/Pinnacle and Illinois in Advocate/North Shore. States generally are supportive of the FTC and hostile to concentration.

Where is provider merger antitrust enforcement going? There certainly continue to be big deals in the provider segment, such as the recent announcements of transactions between the University of Pittsburg Medical Center and Pinnacle Health and Partners and Care New England. In addition, there is the potential for the FTC to focus on other types of provider mergers, such as cross-market mergers across different provider types or adjacent geographies.

There is economic evidence suggesting that these types of mergers can lead to upward pressure on reimbursement rates due to greater provider bargaining leverage and, therefore, that they are anticompetitive. To go after this kind of case would push the envelope for the FTC—but the agency could decide to act on the basis of sound economic theory. At the end of the day, it’s more likely that the FTC is going to take a relatively conservative approach and stick to cases that are in line with the enforcement proceedings it has brought in the past.

Using COPAs to Avoid Federal Enforcement

As federal enforcement has become tighter, some states have turned to state Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA) laws, which entitle the state Department of Health to grant a certificate that immunizes the transaction from federal antitrust oversight. There have been several recent examples of state action protection being tested. For example, in Cabell/St. Mary’s, West Virginia introduced a COPA law under which it would allow the merger to go ahead after the FTC had decided to challenge the transaction in court. The FTC was subsequently forced to withdraw its challenge because under the COPA law, the transaction was immune from federal antitrust enforcement.

The FTC is hostile to these kinds of mechanisms to exempt transactions from the federal antitrust laws. The jury’s still out, however, on how effective they are—and whether their impact on competition has had any adverse effects on the market.

Insurance M&A Under the New Administration

There are a lot of lessons to be learned from the unsuccessful Aetna/Humana and Anthem/Cigna deals. The biggest learning from the Anthem/Cigna deal is that culture remains the most underdiligenced enemy of M&A transactions. Anthem and Cigna hit some cultural shoals during their engagement. It’s a cautionary note that when considering a merger, efforts should be made to ensure there is a cultural match.

It’s important to note that Aetna, Humana, Cigna and Anthem—as well as many others—are still looking for partners, particularly in the Medicare and Medicaid space. They must acquire to grow, and they all have a lot of cash to deploy.

Where are we likely to see growth? The employer market is the largest and most stable, so it probably will not see much movement. Some of the smaller players will certainly be picked up and traded—but even if the employer mandate is repealed, nothing’s likely to change. It’s likely payers that have achieved success in the employer market will realize that they’re over-concentrated there and seek to expand their product lines, particularly into the faster-growing government sectors, such as Medicare Advantage (MA).

Medicare is the third rail of American politics. Even though some more extreme members might like to, the GOP-controlled Congress can’t get rid of Medicare—but it can support efforts to push Medicare members into private MA plans. Therefore, MA is an important sector to watch in today’s political reality. About 25% of the MA market share is outside of the “big seven” payers, leaving a lot of opportunity for transactions and growth.

Medicaid is another area that probably will see a lot of activity. What does that mean in terms of the M&A market? The prevailing sentiment is uncertainty. ACA repeal-replace is in flux, but the direction is clear. The goal of the Trump administration and the GOP Congress is to convert existing entitlement programs to block grants/per capita allotments, which could be a disaster for states, bringing cuts to funding and increases in uninsured rates.

In terms of M&A, however, block grants—which mean greater flexibility for states—present an opportunity for commercial players and payers. Some states already are speaking about potential commercial partnerships with private managed care organizations. The current political climate is likely to accelerate the march toward a public/private benefits administration paradigm, bringing an increased role for commercial players.

The M&A market also is focusing increasingly on joint venturing and cross-platform investing. More and more insurers are deploying capital to build service units or make other alternative investments. In addition, insurers are building joint ventures with other players in different segments, such as hospital systems, pharmacy benefit managers and ambulatory care providers. This allows insurers both to diversify their revenue streams and to position themselves defensively against their competitors.

The new environment brings regulatory concerns. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)always will be an issue for companies with significant Medicare revenues. It’s possible that a Trump administration could loosen regulatory constraints.

State regulators also can present issues and increase costs. For example, Centene won approval to purchase Health Net in California only after agreeing to keep its headquarters in the state and spend $350 million on community health measures.

Health Insurer Antitrust Enforcement

Before Aetna/Humana and Anthem/Cigna, the DOJ had reviewed several other health insurer mergers, and obtained consent decrees requiring divestitures to address potential competitive concerns in five of them. After several of these deals, there were economic studies looking at the impact of transferring MA lives to see whether competition had been maintained in relevant markets. The results showed that divestitures had not been successful in containing pricing. The recent megamergers were an opportunity for the DOJ to test its theories of competitive harm in court, using this evidence.

What are the main takeaways from the Aetna/Humana and Anthem/Cigna decisions? Both courts accepted the DOJ’s position on narrow market definitions. In Aetna/Humana, the judge agreed with the DOJ that Medicare Advantage was a separate market from traditional Medicare. Once that decision was made, there were 364 counties where both Aetna and Humana offered MA plans, which the court found could result in a monopoly.

Anthem/Cigna presented a different issue. In that case, the focus was on the provision of an administrative services only (ASO) contract to large national accounts, which the court defined as companies with more than 5,000 employees spread over at least two states. Looking only at that customer segment, the court found that there are just four insurance companies capable of offering national services, and the merger would reduce that number to three, making the transaction anticompetitive.

These cases illustrate that agencies and courts will look critically at any potential divestitures. Although Aetna spun off certain MA plans representing 290,000 members in 437 counties to Molina, the court was skeptical of Molina’s ability to take on the MA business—a concern echoed in documents authored by Molina’s executives. That development is a cautionary tale about how things beyond a company’s control can make the process more difficult.

There are other key health insurer antitrust cases underway. For example, there is an in re Blue Cross Blue Shield class action litigation going on which could be a market disrupter. There were two class actions, consolidated in Alabama, that allege the Blues’ system of dividing states between themselves and putting limitations on Blues companies’ ability to have non-Blues’ business is effectively a market restraint. The outcome of this case has the potential to shake things up in the insurance market and open up opportunities for deal making.

Overall, the DOJ is in a relatively strong position. Deals among the five largest insurers are likely to face significant antitrust headwinds; but, the devil is in the details. It is important to identify specific business overlaps to uncover possible issues.

Conclusion: Trends to Watch and Considerations for Deal Execution

To summarize the current trends in the healthcare M&A market:

- Consolidation across most segments is expected to continue—at least until the “irresistible M&A force” runs into the “immovable antitrust object”;

- Wellness, population health management and digital health technologies are likely to continue to be high-growth areas, with the managed care space likely to remain active following the termination of the recent Anthem/Cigna and Aetna/Humana transactions;

- Novel and creative strategic relationships will continue to develop among industry participants to adapt to the dynamics of the marketplace; and

- As an outgrowth of these new relationships, there should be expansion in the number and type of potential investors and funding sources, including through private equity.

In terms of transaction execution, there are several areas that are commanding increased attention and resources:

- Regulatory Compliance. Parties are devoting significant resources for confirming Stark and Anti-Kickback Statute compliance—not just in terms of historical compliance (with billing and coding audits, contract reviews, etc.), but also in terms of the quality and scope of the target’s policies and procedures to ensure that an ongoing “culture of compliance” exists. If and when issues are uncovered, there are frequently discussions between buyers and sellers as to whether the matter is of a nature that should require self-reporting (and if so, who bears the economic and operating risks that might result from the self-report).

- Privacy and Data Security. While privacy and data security are increasingly relevant to all business enterprises, the healthcare industry presents some unique risks and challenges, given that protected health information (PHI) and other sensitive information are central to the services provided and the industry’s processes generally. As providers, systems, payers and other participants become even more interconnected through technology and integrated delivery systems, the potential for security breaches—and the resulting implications—are likely to increase exponentially. Therefore, deal participants are spending significant time and resources to scrub current IT and related systems, identify any known breaches and assess any vulnerabilities (and the costs to address them). Privacy and data security, along with regulatory compliance, are also key focus points when it comes to negotiating representations and warranties and related indemnity provisions. In some instances, the parties end up negotiating separate parameters around these subjects in terms of baskets, caps and survival periods. There is also increased interest in considering representation and warranty insurance or other insurance coverage to manage these risks.

- Valuation Reports and Analyses. In the area of diligence, valuation analyses and reports are commonplace in many transactions to support the parties’ determinations as to fair market value and commercial reasonability (i.e., under Stark and Anti-Kickback regulations). Among other things, it is important to address the scope and methodology of any such report early in the deal process, and with appropriate input from legal counsel.

- Antitrust. It’s obviously important at the outset of transaction discussions to conduct a realistic assessment of antitrust risks and concerns presented by the proposed transaction. There needs to be candid and informed discussions of how the market is likely to be defined in each instance, where the overlapping operations are and what the options are for addressing these matters with the appropriate regulators, whether at the federal or state level. Parties should also anticipate a candid discussion and negotiation of which side bears the risk of a failure to gain antitrust approval.

In addition, both teams need to be thoughtful in preparing board books, management presentations and other internal communications (i.e., so-called 4(c) documents for purposes of Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filings), with an eye toward the likelihood that these will be produced to antitrust regulators and will factor into their analyses. There is a tension here, in that internal communications often seek to support the transaction by showing the positive impacts that the transaction will have on such things as market share, pricing power, ability to compete more effectively with others, etc. The fact is, however, that these statements will be viewed in a much different light by the antitrust regulators. Accordingly, communications need to be crafted thoughtfully and strategically (and hopefully, with the benefit of legal input) to avoid potential pitfalls down the road.

Finally, to the extent that the diligence process will include a review of payer contracts or other sensitive pricing information, parties should be very thoughtful about the manner and timing for this specific process. There are a number of approaches that can work, but they generally involve providing only high-level, “bundled” or de-identified data at the early stages to help inform a go/no-go or pricing decision, with a follow-on process that may involve a review conducted by a third party who will once again report only limited data to the other side. The goal is not only to preserve the integrity of the deal from the standpoint of antitrust review, but also to avoid potential antitrust issues down the road should the parties not proceed with a transaction and remain competitors in the marketplace. - State and Local Government Approvals. Many transactions—particularly hospital and payer combinations—will typically require some level of state or local government approvals. The parties should, of course, identify the applicable approvals up front, and develop a strategy and game plan for advancing the transaction with the appropriate agencies. In doing so, it is important to identify at the outset individuals or groups who may be opposed to the transaction based on their own agendas—e.g., other competitors, labor unions or other issue advocacy groups—and then develop a strategy for responding to these groups’ arguments. A question that is also likely to come up in the negotiations is the extent to which one or the other parties to the transaction must agree to make financial commitments or other commitments pertaining to its business operations if required as a condition of obtaining these approvals.

- Closing Conditions. With regard to closing conditions, parties are carefully evaluating any kind of material adverse change (MAC) condition in the context of the current political climate and resulting market uncertainty. Unlike many closing conditions that have become somewhat standardized, the MAC condition can take on added significance in negotiations, given the prospect for actions to repeal and replace Obamacare, reduce federal funding for Medicaid, etc. One can guard against these risks by framing the condition to exclude changes or effects on the industry generally, but the parties may want to anticipate possible changes that could have a disproportionate impact on the target, and then allocate the risk between them accordingly.

- Post-transaction Considerations. It’s never too early to focus on postdeal integration planning from operations, governance and other relevant perspectives. In addition, communication plans are essential, from the initial announcement through the closing and beyond. The plan should encompass both internal and external communications and, if applicable, factor in compliance with relevant securities laws. Finally, with novel deal structures being presented, lawyers are spending increased amounts of time working with clients on post-transaction governance and related structures. In instances in which a party is being acquired in total, there may not be much mystery, but in the context of affiliations, joint ventures and other forms of strategic relationships, governance structures and associated decision matrices can often take a fair amount of creativity and, ultimately, time to negotiate and document.

PAC Networks: Surging Growth Optimizes Patient Care Across Settings

By Stephanie Anthony, Director, Manatt Health | Alex Morin, Senior Manager, Manatt Health | Carol Raphael, Senior Advisor, Manatt Health

Post-Acute Care Perspectives for Hospitals and Health Systems

Hospitals and health systems are increasingly focused on post-acute care (PAC) services and developing a strategy to better incorporate them into their clinical delivery models. The increased focus is driven by a number of factors including:

- Americans are living longer, often with chronic and disabling conditions. By 2040, 1 in 5 Americans will be 65 or older, with more than one-third living with a disability.

- The nature of illness is shifting away from acute episodes to chronic disease. This shift requires a model of care that extends outside of hospitals’ walls and leverages medical advances across nonhospital sites of care, leading to the formation of integrated delivery systems

- The “specialization” of American medicine that has occurred over the past 60 years is being challenged to piece itself back together across provider types and sites of care. Integrated approaches enable healthcare professionals to treat patients holistically and collaboratively, improving care quality and outcomes.

- There are broad changes in reimbursement models. New models—including financial penalties for readmissions, value-based payment and site-neutral payment—will continue to grow, incentivizing health systems to work more closely with post-acute providers who help ensure continuity of care and address complications that can reduce hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) use.

The Trends Driving PAC Preferred Provider Networks

Medicare reimbursement rates have been stagnant in recent years, placing significant pressure on PAC providers despite historically high Medicare margins. Medicare is focused on lowering overall PAC utilization by tightening requirements for providers to receive payments and using reimbursement policy changes to curb unnecessary utilization, as well as to rationalize care provided across settings.

Notably, the Medicaid Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has issued a recommendation for a possible “unified payment system” for PAC that would establish single placement criteria and a common payment system for all sites of care. Though unlikely in the immediate term, the future of PAC payment will continue to shift toward risk-adjusted, site-neutral payments and tests of value-based payment models, including acute-post-acute care bundles.

A major result of these trends has been the formation of PAC “preferred provider networks” by hospitals and health systems. While some organizations are strategically looking to buy or build PAC services as part of their owned network of services, more are instead looking to integrate with PAC by creating networks of preferred providers that collaborate to optimize patient care across settings. A recent Premier survey of executives from 82 hospitals and health systems found that 95% of all respondents indicated that the development of high-value PAC networks to support population health was cited as a key area of focus over the next three years.

The formation of PAC preferred provider networks is complex, and requires a clear understanding of referral patterns to PAC providers, PAC financial and quality performance, PAC providers’ capacity and ability to serve patients from certain geographies, and varying levels of acuity. It also demands identifying the health system’s need for PAC services, as well as its knowledge of the legal and compliance risks associated with forming PAC networks. Thoughtful planning is essential to develop a robust network where the hospital and the PAC providers agree to a standardized set of policies and procedures that optimize patient care, both during the transition and after the patient is being serviced by the PAC provider.

Benefits of PAC Preferred Provider Networks

PAC preferred provider networks bring many benefits, both to the hospital and to the participating PAC provider:

1. Hospital Benefits

- Immediate and consistent access to PAC services to appropriately and efficiently place patients in the right levels of care regardless of payer type

- Increased hospital throughput

- Greater efficiency in the discharge process

- Ability to develop a care coordination infrastructure that seamlessly connects all providers along the care continuum

- Reduction in readmissions/unnecessary ED visits

- Brand and patient loyalty improvement

2. PAC Provider Benefits

- Consistent and more predictable referral volumes

- Better access to clinical support from the hospital to keep patients in the PAC facility rather than transferring them back to the hospital

- Competitive differentiation

- Preparation for new reimbursement models that bundle acute care and PAC together and/or include shared savings targets

- Brand opportunities derived from network participation

3. Joint Benefits

- Patient data sharing, as well as the integration of data among sites of care and an enhanced focus on analytics to improve patient care

- The ability to jointly develop quality improvement initiatives to keep patients in the right levels of care

- Shared protocols and clinical pathways to maximize the effectiveness of treatments and treat patients proactively rather than reactively

- Consistent patient transfer protocols and processes

- Continuous communication and collaborative patient management

- Ability to individually and jointly market care services, using outcomes that measure care quality and patient experience

- Preparation for success in population health and value-based payment initiatives

Conclusion

PAC providers play a critical role in ensuring patients receive the care they need to recover after a hospital discharge. As the population ages, chronic disease rates increase and new reimbursement models are introduced, a growing number of hospitals and health systems are seeking to integrate PAC providers into their care models—most often by creating collaborative preferred provider networks focused on optimal cross-setting patient care.

As more and more health systems consider the development of these networks, Manatt can provide the legal, advisory and analytic insights—as well as the deep knowledge and experience in hospital/health system and PAC strategy—to support their success. For more information, contact Stephanie Anthony at santhony@manatt.com or 212.790.4505.

CMS Issues Rules to Help Stabilize Health Insurance Market

By John M. LeBlanc, Partner, Healthcare Litigation | Andrew H. Struve, Partner, Healthcare Litigation | Samuel A. Canales, Associate, Healthcare Litigation

On April 13, 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued the final market stabilization rule (Final Rule) under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to help stabilize individual and small group markets. According to a press release by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the government intervention was necessary to remedy the following instabilities:

- Approximately one-third of counties in the United States have only one insurer participating in their Affordable Health Benefits Exchange (Exchange) for 2017.

- Five states have only one insurer participating in their Exchanges for 2017.

- The premium for the benchmark second-lowest-cost “silver plan” on HealthCare.gov increased by an average of 25% from 2016 to 2017.

- Approximately 500,000 fewer Americans selected a plan during the Exchange open enrollment period in 2017 than in 2016.

- Many states saw double-digit increases in their insurance premiums for 2017, including:

- Arizona—116%

- Oklahoma—69%

- Tennessee—63%

- Alabama—58%

- Pennsylvania—53%

While the Final Rule appears to refine the ACA, its accompanying press release makes clear that the Trump administration still believes the ACA is unsustainable in the long term. Nevertheless, a key component of the Final Rule is its effort to address abuses pertaining to special enrollment periods.

Open Enrollment and Special Enrollment Periods

The ACA created open enrollment and special enrollment periods (SEPs). During these periods, qualified individuals can enroll in ACA-qualified health plans through a state-created Exchange.

Absent special circumstances, individuals typically enroll in new Exchange coverage, or change existing coverage, during an open enrollment period, which occurs once yearly. In 2017, the open enrollment period was reduced to 45 days.

In contrast, SEPs occur outside of an open enrollment period and generally last up to 60 days from the occurrence of a qualifying life event, which includes (1) loss of health coverage, (2) changes in household, (3) changes in residence, and (4) other qualifying events such as leaving incarceration or becoming a United States citizen.

Concerns Regarding Special Enrollment Period Pre-enrollment Eligibility

Open enrollment periods are meant to incentivize individuals to obtain yearlong coverage during a predefined, scheduled period. SEPs, on the other hand, are designed to address unforeseen life-changing events that happen outside of an open enrollment period. Health insurers, however, have long complained that inadequate enforcement of the SEP pre-enrollment eligibility standards has resulted in abuses.

The most notable abuse is the use of SEPs by ineligible individuals. For example, health insurers have reported that a substantial number of individuals are choosing to forgo purchasing health insurance coverage unless and until they become sick and require expensive care. As acknowledged in the preamble to the Final Rule, “policies and practices that allow individuals to remain uninsured and wait to enroll in coverage through a special enrollment period only after becoming sick can contribute to market destabilization and reduced issuer participation, which can reduce the availability of coverage for individuals.”

SEPs promote this behavior when pre-enrollment eligibility standards are not enforced such that individuals can easily misuse these periods to obtain coverage, effectively, at any time (e.g., whenever they get sick). In particular, there has been concern regarding the accuracy of claimed qualifying life events. The preamble states that “allowing previously uninsured individuals to enroll in coverage via a special enrollment period that they would not otherwise qualify for can increase the risk of adverse selection, negatively impact the risk pool, contribute to gaps in coverage, and contribute to market instability and reduced issuer participation.”

Accordingly, in 2016, the CMS issued warnings and took preliminary actions to address SEP misuses. The CMS also proposed a pilot program that would require HHS to verify the pre-enrollment eligibility of 50% of new SEP applications starting in 2017. Based on feedback from health insurers, the CMS elected to strengthen its enforcement stance even more.

Changes to Special Enrollment Period Pre-enrollment Eligibility Enforcement

Before the Final Rule, in most cases, individuals who enrolled through an SEP self-attested to their qualifying life events. However, the Final Rule is “increasing pre-enrollment verification of all applicable individual market special enrollment periods for all States served by the HealthCare.gov platform from 50 to 100 percent of new consumers who seek to enroll in Exchange coverage through these special enrollment periods.” All new SEP applications will remain “pending” until HHS confirms the occurrence of a qualifying life event. “In this context, ‘pending’ means the Exchange will hold the information regarding [qualified health plan] selection and coverage start date until special enrollment period eligibility is confirmed, and only then release the enrollment information to the relevant issuer.” Applicants will have 30 days to provide documentation showing their eligibility.

The Final Rule will go into effect June 19, 2017. Its verification requirement will apply to all new consumers in states served by the HealthCare.gov platform, including Federally-Facilitated Exchanges and State-Based Exchanges on federal platforms. The verification process will be phased in, focusing first on the most commonly used qualifying life events (and those of most concern), including permanent move, loss of minimum essential coverage, marriage and adoption.

Conclusion

While reactions to the Final Rule have been predictably mixed, the Final Rule may have a constructive impact by making it more difficult for individuals to abuse the SEP pre-enrollment qualifying limitations. Whether this will help stabilize the Exchange marketplace is a question that will not soon be answered.

New Webinar: HIPAA and Emerging Technologies

Join Us June 6, from 2:00–3:30 p.m. ET. Click Here to Register Free—and Earn CLE.

New technologies are transforming healthcare. According to a HIMSS Mobile Technology Survey of healthcare provider employees, about 90% say they are using mobile devices to engage patients in their healthcare—and 36% believe app-enabled patient portals are the most effective patient engagement tool. A Spyglass Consulting Report reveals that an astounding 96% of physicians use text messaging for patient care coordination—and 30% say they’ve received protected health information(PHI) via text.

How can you take advantage of the power these new tools offer while ensuring full compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)? Find out in a new Manatt webinar for Bloomberg BNA, “HIPAA and Emerging Technologies: Protecting Privacy When Communicating in the Digital Age.” The CLE-eligible program will:

- Identify the qualities to look for when choosing vendors and platforms to enable health-related communications while ensuring HIPAA compliance.

- Explore how to provide ongoing oversight to protect your organization after vendors and platforms have been deployed.

- Reveal how to avoid common HIPAA traps that organizations fall into when using new technologies.

- Explain how to put digital tools to work optimizing communications and organizational workflow while mitigating risk.

- Outline the steps to follow if a breach does occur.

With texting, apps and portals reshaping healthcare at the same time privacy concerns are mounting, this is a “must attend” program. Even if you can’t make the original airing on June 6, click here to register free now and receive a link to view the program on demand.

Presenters:

Jill DeGraff, Partner, Manatt Health

Helen Pfister, Partner, Manatt Health

Randi Seigel, Counsel, Manatt Health

The Goldilocks Theory of Bringing Change to the FDA

By Ian Spatz, Senior Advisor, Manatt Health

Editor’s Note: The nomination of Dr. Scott Gottlieb—who has now been confirmed to lead the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—drove another Goldilocks debate. Like the fairy tale heroine who tested three bowls of porridge to find one too hot, one too cold and one just right, participants debated whether today’s FDA is too lenient, too tough or just right in reviewing prescription drugs. In a recent post for the Health Affairs Blog, written prior to Dr. Gottlieb’s confirmation and summarized below, Manatt Health examines the views of both the critics and supporters of Dr. Gottlieb, as well as the challenges that he will face as the new commissioner. Click here to read the full post.

_____________________________________________

Dr. Gottlieb is clearly qualified to assume the role of FDA commissioner. What critics take issue with is whether his extensive experience ties him too closely to the entities he will be regulating and whether the views he’s expressed show a disregard for the FDA’s public health role. Supporters counter that his detailed industry knowledge will make him a more effective regulator and his writings demonstrate that he’s thought about the toughest issues.

Those who seek to judge what Dr. Gottlieb will do as leader of the FDA try to discern where he will come down on the simplistic porridge question. This question masks the far more complex challenges he’ll face—the limits of science in dealing with the uncertainty about the safety and effectiveness of new medicines, the proper role of the FDA when it can no longer control information on drugs, and the issues around drug pricing.

The Limits of Science

In its role of deciding whether to license new prescription drugs and describe their benefits and risks, the FDA wrestles with the limits of science to resolve uncertainty. Resources, time and the recognition that patients are waiting limit the size and length of clinical trials. At the same time, rigorous trials are necessary for discovering whether drugs are effective and discerning potential side effects. The FDA staff has brought great skill and judgment to balancing these challenges throughout both Democratic and Republican administrations. While the veneer of the FDA is political, those making the decisions are career staff whose esprit and perseverance are a strong rebuke to critics of federal employees.

Dr. Gottlieb can encourage the career staff in examining their procedures and putting the latest tools to work in resolving uncertainty, including new methods of trial design and statistical analysis, as well as the use of real-world evidence post-approval to assess benefits and risks. To the extent these new tools reduce uncertainty in drug approvals, we all win.

Medical Information

The FDA not only approves a new drug but also delineates what manufacturers may (or must) say about its benefits and risks. When drug information was largely limited to medical journal advertisements, drug company sales pieces and direct-to-consumer ads, this made sense. Today, however, medical information is freely accessible through any search engine.

Dr. Gottlieb has the opportunity to help the FDA navigate this new world where it is less able to control information. He can challenge the agency to adapt its rule to prevent companies from making unsubstantiated claims but allow them to participate in a truthful dialogue with doctors and patients.

In December, the FDA announced some commonsense rules to open up discussions between drug companies and health plans, such as a draft guidance on how drug companies can communicate with payers about healthcare-related economic information. Dr. Gottlieb can build on these kinds of initiatives.

Pricing

Though the FDA has maintained that it does not have a direct role in drug pricing, the current volume of the debate will make it harder to stay on the sidelines. In Dr. Gottlieb, the FDA has a leader who has worked at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and thought deeply about drug pricing. While it’s unlikely Dr. Gottlieb would disturb the FDA’s traditional abhorrence of drug importation, he can play a role in encouraging the competition that health plans and other purchasers could leverage to control costs.

One tool would be to focus on making the new biosimilar pathway work, including publishing final guidance. Another would be to speed the approval of generic drugs where there is little to no current competition.

Conclusion

The challenges that the FDA faces are great and will be even greater if its resources are cut as proposed in the president’s budget. Yet the agency and its leaders have consistently tuned out the noise of those arguing that the regulatory porridge is too hot or too cold in order to advance their mission.

Proposed 2018 Uncompensated Care Payment Methodology—Implications for Hospitals

By Steve Chiu, Associate, Manatt Health | Harvey Rochman, Partner, Litigation

Hospitals qualifying for the Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) program that receive uncompensated care payments should be aware that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has resurrected its proposal to begin phasing in the use of uncompensated care data reported in Worksheet S-10 to calculate such payments beginning in 2018. This could result in significant changes to the distribution of uncompensated care payments.

Background

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) contained numerous provisions intended to reduce and redirect overall Medicare DSH payments as more individuals obtain health coverage through the ACA’s coverage expansion provisions. These Medicare DSH reform provisions included the establishment of the uncompensated care payment. This payment takes 75% of the former Medicare DSH payment amount, reduces that amount according to the change in the national uninsured rate and redirects the remainder to hospitals that continue to deliver high levels of uncompensated care.

Proposed Changes to the Calculation of Uncompensated Care Payments

In the recently published 2018 Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Proposed Rule (82 Fed. Reg. 19807 (Apr. 28, 2017)), CMS proposes to jump-start its earlier plan to begin using data from Worksheet S-10 of a hospital’s Medicare cost report to calculate uncompensated care payments.

Specifically, CMS is now proposing to compute Factor 3 (i.e., the hospital-specific factor of uncompensated care payment calculations) for each hospital for FY 2018 using a 2012-2014 three-year average consisting of:

- Medicaid patient days (from FY 2012 cost report data) and Medicare Supplemental Security Income (SSI) patient days (from the FY 2014 SSI ratio);

- Medicaid patient days (from FY 2013 cost report data) and Medicare SSI patient days (from the FY 2015 SSI ratio); and

- FY 2014 Worksheet S-10 data.1

If this proposed rule is finalized, CMS expects Factor 3 to be calculated entirely based upon S-10 data by FY 2020. FY 2019’s three-year average would contain two years’ worth of S-10 data (FY 2014 and 2015) along with one year of Medicaid and Medicare SSI patient days (Medicaid days from FY 2013 cost report data, Medicare SSI days from the FY 2015 SSI ratio) and in FY 2020, the Factor 3 calculation would be based entirely on S-10 data (from FY 2014-2016).

With respect to the exact S-10 data that would be counted in the FY 2018 uncompensated care payment calculations, CMS is proposing that uncompensated care would be defined as the amount on line 30 of Worksheet S-10, which is the combined cost of charity care (from Line 23) and the cost of non-Medicare bad debt (from Line 29). CMS had previously considered including Medicaid shortfalls in the uncompensated care payment calculations, but is not currently proposing to do so.

CMS has also updated the cost-reporting instructions associated with Worksheet S-10 and is revising its internal standardized instructions that tell Medicare Administrative Contractors when and how often a hospital’s Worksheet S-10 should be reviewed. CMS believes that FY 2017 Worksheet S-10 data would be the earliest S-10 data subject to a desk review.

This Is the Plan and CMS Is (Probably) Sticking to It

Though CMS has backed away from similar plans to use Worksheet S-10 data in the past, this time it is less likely that CMS will do so. In the 2017 Medicare IPPS Final Rule, CMS had scrapped its plans to use S-10 data for 2018 in light of public comments relating to quality control concerns with S-10 data and had stated that S-10 data would be used “no later than FY 2021.”

However, this time around, to bolster its decision to use Worksheet S-10 data to calculate uncompensated care payment, CMS made two main observations:

- 2014 was the “tipping point” for S-10 data improvement. CMS noted that the S-10 data were becoming good measures of the amount of uncompensated care a hospital delivers, and had reached a “tipping point” in 2014 when S-10 data produced better measures of Factor 3 than the proxy methodology based on Medicaid and Medicare SSI patient days. CMS cited several studies showing that the correlation between the amounts for Factor 3 calculated from the IRS Form 990, Schedule H, and Worksheet S-10 had increased over time and that the correlation was expected to be significantly greater between Schedule H and Worksheet S-10 Factor 3 calculations for 2014, when compared with Factor 3 amounts derived from Medicaid and Medicare SSI days.

- Use of 2014 Medicaid patient days to calculate Factor 3 would unfairly penalize hospitals in states not expanding Medicaid. 2014 was the first year of Medicaid expansion under the ACA and hospitals operating in states which had expanded Medicaid eligibility then would likely experience a decrease in their uncompensated care burden for 2014, as many of the hospitals’ previously uninsured patients would have been able to pay for services with their newly gained Medicaid coverage. Paradoxically, basing uncompensated care payments on Medicaid days would simultaneously give these hospitals a larger share of the uncompensated care payment pool (due to the hospitals’ increased number of Medicaid days) than would be available to hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid.

What Hospitals Should Do Now

As a threshold matter, hospitals that have concerns with this proposal should submit a comment letter to CMS stating the concerns and proposing alternative policies. Comments regarding the 2018 Medicare IPPS Proposed Rule are due by 5 p.m. ET on June 13, 2017.

Assuming that this proposed rule is finalized as written, hospitals should review the uncompensated care data they reported in their 2014–2016 cost reports via the Worksheet S-10. If that data is not accurate (or nonexistent), hospitals should determine whether they can amend or adjust such data.

A further step that hospitals should take is to re-examine their financial assistance policies and revenue cycle operations. CMS’s comments make clear that the ultimate goal is to align the uncompensated care values that a hospital reports via its Form 990, Schedule H, with the uncompensated care values that a hospital reports via Worksheet S-10 of its Medicare cost report. Both of these reporting obligations require a hospital to report its amounts of charity care and bad debt. The amount of reportable charity care and bad debt depends, in turn, on the terms of a hospital’s financial assistance policies and the hospital’s revenue cycle operations (including collections and accounting practices).

Even longer-term actions that hospitals can undertake in this area would involve re-examining their community health needs assessments and any other community benefit and charity care obligations they may have (e.g., to maintain tax-exempt status, via consent agreements with their state attorneys general). The task may be daunting, but the benefits of aligning a hospital’s community health strategy, financial assistance policies, revenue cycle operations, tax accounting and Medicare cost reporting are immense—for both hospitals and the communities they serve.

1Puerto Rico and IHS/Tribal hospitals and new hospitals would be subject to a different Factor 3 calculation methodology, and different methodologies would apply to hospitals that have data not lining up with the periods specified above.

Insurer Merger Saga Ends Without Guidance on Efficiency Claims

By Lisl J. Dunlop, Partner, Antitrust and Competition | Shoshana S. Speiser, Associate, Litigation

Prior to calling off its nearly two-year fight to acquire competing insurer Cigna last week, Anthem urged the Supreme Court of the United States to hear its appeal from the lower courts’ rejections of its claims of significant efficiencies from the deal. Efficiency arguments are a mainstay of many healthcare merger defenses, appearing frequently in provider merger cases, as well as the recent insurance cases. Since the federal courts have been fairly hostile to the ability of efficiencies claims to overcome the presumptive anticompetitive effects generated by significant concentration, direction from the Supreme Court on this issue would have had important ramifications for how transactions are defended and the likelihood of getting tough deals through the agencies and the courts.

As we reported in a “Health Update” article earlier this year, the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice successfully sought injunctions in the D.C. District Court blocking two proposed health insurer mergers: Aetna/Humana and Anthem/Cigna. While Aetna and Humana abandoned their transaction shortly after the district court decision, leaving Humana with a $1 billion termination fee, Anthem continued fighting in pursuit of its transaction. Despite initial attempts by Cigna to terminate the transaction (and claim the $1.85 billion breakup fee and $13 billion in damages), Anthem appealed the decision to the D.C. Court of Appeals and released statements regarding its hope for a change of tune from the DOJ with the new administration.

The appeal to the D.C. Court of Appeals focused on the district court’s treatment of Anthem’s claims that the transaction would lead to significant efficiencies in the form of $2.4 billion in reduced costs of consumer medical claims through lower provider rates, much of which would immediately accrue to self-insured employers who retained Anthem to provide administrative services. Last month, in a split decision the court of appeals ruled against Anthem.

The majority of the court of appeals held that Anthem had failed to show the requisite “extraordinary efficiencies necessary to offset the conceded anticompetitive effect” of losing Cigna as a competitor. Despite acknowledging the widespread acceptance of the potential benefits of efficiencies and some circuit court decisions to the contrary, the majority opined that efficiencies cannot serve as a defense to an anticompetitive merger. The majority went further and held that, even assuming the availability of an efficiencies defense, Anthem’s purported savings were not merger-specific or were unsupported by the evidence.

But Anthem did win over one judge. In a dissenting opinion, Judge Kavanagh argued in favor of a modern economic approach in which the inquiry does not end with the determination of increased market share and concentration. Instead, courts must consider efficiencies and consumer benefits together with anticompetitive effects. As a result, the dissent found that even though the merger would likely result in some fee increases and not all of the projected savings would be realized by customers, the transaction would still yield savings in an order of magnitude greater than the projected fee increases.

Notably, the dissent focused on the DOJ’s concession that the merged entity would be able to obtain lower provider rates and the DOJ expert’s failure to calculate savings. The dissent also found that the efficiencies were merger-specific (because they would flow directly from Anthem’s increased bargaining leverage stemming from the merger) and adequately verified (by Anthem’s expert and integration planning team, healthcare providers and an independent consulting firm).

Interestingly, the dissent also found that those same reduced provider rates that Anthem claimed as an efficiency could also support an argument against the merger if Anthem was able to push provider rates below competitive levels, and would have remanded the case back to the district court for consideration of that issue.

Anthem Urges the Supreme Court to Resolve the Circuit Split

In its petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court, Anthem urged the Supreme Court to step in to resolve the circuit split between decisions foreclosing consideration of efficiencies relying on “outdated 1960s antitrust law[,]”1 and those recognizing efficiencies in merger analysis. Anthem argued that the district court and majority of the court of appeals had applied a disproportionately high burden of proof on Anthem and had failed to quantify the portion of efficiencies they rejected and weigh the remainder against the anticompetitive price increases to recognize that the transaction would benefit consumers. Anthem also highlighted the Supreme Court’s focus in other areas of antitrust jurisprudence on the purpose of the antitrust laws as protecting consumer welfare rather than competitors, the limited number of cases that provide the Supreme Court with an opportunity to review merger antitrust questions, and rising healthcare costs.

Although chances were slim that the Supreme Court would take up the appeal (particularly since it has not reviewed a merger challenge in over 40 years), the antitrust bar was watching closely to see whether this could have provided clarity on the standards for assessing merger efficiencies. Alas, this is not to be, as Anthem called off the transaction after a loss in Delaware court over Cigna’s attempted termination of the merger agreement. For now, parties to transactions resulting in high concentration levels must accept that efficiency claims will be subject to a stringent level of proof as well as some skepticism by regulators and the courts.

1These decisions include the Third Circuit’s decision in Penn State Hershey and the Ninth Circuit’s decision in St. Luke’s.

New Act Allows Creation of Federally Regulated Association Health Plans

By Kevin Casey McAvey, Senior Manager, Manatt Health | Joel Ario, Managing Director, Manatt Health

In March, as House Republican leadership reconsidered their vote options on the American Health Care Act (AHCA) they pressed forward with bills in the party’s third bucket of healthcare reforms—legislative actions that require consideration under regular order.1 Backed by the Trump administration, on March 23, the House passed the Small Business Health Fairness Act of 2017 (SBHFA) in a largely party-line vote of 236-175.2 The SBHFA would amend the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) to allow for the creation of association health plans (AHPs)—plans that would enable small employers to negotiate and purchase health insurance collectively across state lines.3 AHPs would be federally regulated and exempt from individual state regulations and assessments.

AHPs have been a top priority for small business advocacy organizations and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for decades.4 In 2005, U.S. Republican Senators Olympia Snowe and Jim Talent introduced an earlier incarnation of the SBHFA (of 2005), following the ninth passage of the similarly named bill in the House, only to have its passage stall.5 AHPs have been a staple of pre-AHCA Affordable Care Act (ACA) repeal proposals, including the proposal from then-Representative Tom Price (now Secretary of U.S. Health and Human Services).6 House Speaker Paul Ryan is also a staunch AHP advocate.

“I love association health plans,” the Speaker has stated, believing them a “market mover.”7 His “A Better Way” policy paper further explains the motivation:

“Small businesses and voluntary organizations—such as alumni organizations, trade associations, and other groups—should have the ability to pool together and offer healthcare coverage at lower prices through improved bargaining power at the negotiating table with insurers just as corporations and labor unions do. By increasing the negotiating power of small businesses with healthcare insurers, AHPs would free employers from costly state-mandated benefit packages and lower their overhead costs.”8

States Strongly Resist AHP Proposals

While they have some strong advocates in business and at the federal level, AHP proposals have faced consistent and stiff resistance at the state level. The National Governors Association, the National Conference of State Legislatures and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) all have persistently advocated against AHPs, believing that they would destabilize local small-group markets and further erode state protections, authority and autonomy.9,10 As the NAIC noted on February 28, it believes AHPs would pull the healthiest and lowest-cost members from small-group markets, leaving employers with older or less healthy memberships with ever-higher premiums:

“We fear the [SBHFA could] increase the cost of insurance for many small businesses whose employees are not members of an AHP. This legislation would encourage AHPs to ‘cherry-pick’ healthy groups by designing benefit packages and setting rates so that unhealthy groups are disadvantaged. This, in turn, would make existing state risk pools even riskier and more expensive for insurance carriers, thus making it even harder for sick groups to afford insurance. In addition, the legislation as written would eliminate all state consumer protections and solvency standards that ensure consumers receive the coverage for which they pay their monthly premium. These protections are the very core of a state regulatory system that has protected consumers for nearly 150 years.”11

The SBHFA would also further accelerate the erosion of state authority in regulating employer-sponsored health insurance, a position otherwise inconsistent with the broader Republican reform agenda.12

For decades, the proportion of residents covered by state-regulated employer-sponsored insurance—those in fully insured health insurance plans—has precipitously declined, as more employers have worked with payers and third-party administrators to implement federally regulated, self-insured arrangements.13 Unlike in fully insured plans, in self-insured plans the employer, not the insurer, bears the financial risk of paying for members’ healthcare claims costs. Similar to AHPs, self-insured plans are pre-empted from most state regulations by ERISA, including reserve requirements, mandated benefits and other state protections.14

The Impact of the Self-Insurance Migration on State Authority

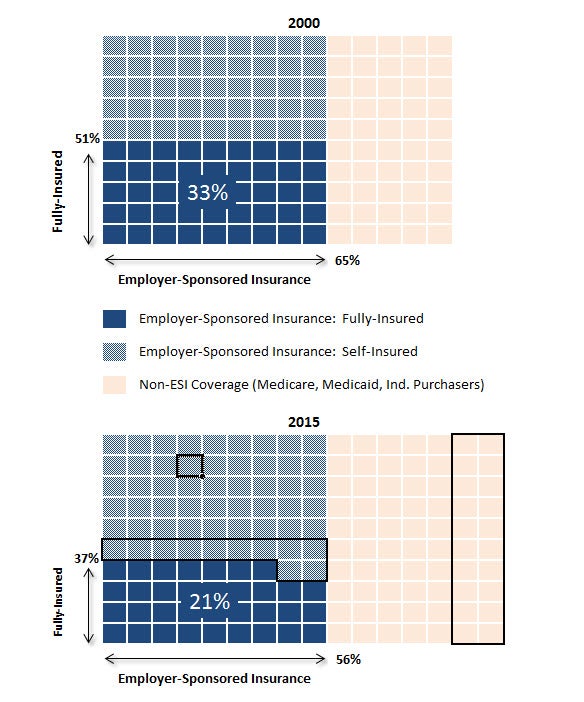

A Manatt analysis of data from American Community Survey and the Kaiser Employer Survey illustrates the impact the self-insurance migration has had on the reach of state authority in the employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) market. Between 2000 and 2015, the proportion of Americans covered by ESI fell by nine percentage points to 56% as ESI membership held constant, while Medicaid and subsidized and unsubsidized exchange membership expanded significantly (Figure 1).15 Over the same period, ESI members covered under state-regulated, fully insured arrangements declined by 14 percentage points—or a percentage point per year—to 37%. Taken together, the proportion of state residents with health insurance who were covered by state ESI regulations fell by approximately a third over the 15-year span, from covering one in three residents in 2000 (33%) to covering barely one in five in 2015 (21%).16

Figure 1: State-Regulated Employer-Sponsored Insurance (2000 vs. 2015)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, 2000 and 2015, available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/health/health-insurance/data.html; Kaiser Employer Survey, 2016, available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey.

Notes: The CPS ASES adjusted methodologies in 2013. A comparison of results between the new and old methods shows a two percentage point (or 5 million member) increase in the proportion of members covered by employer-sponsored insurance that year; thus, changes depicted herein may be conservative. The Kaiser Employer Survey and the CPS ASES utilize different survey methods over different time periods; their results are combined to provide an overall market indicator. Proportions are not precise.

Conclusion

While state authority has simultaneously expanded to cover millions of new “individual purchasers” through state- and federally-facilitated—though federally regulated—health exchanges, the introduction of AHPs could present new challenges to state purview. Sole proprietors, who are currently guided to purchase insurance through the individual marketplaces, may be able to purchase through the proposed AHPs.17,18 Remaining fully insured employers, which tend to be smaller and more averse to self-insured risks, may similarly find AHP offerings attractive.19

States’ ability to regulate their employer-sponsored insurance markets autonomously continues to be challenged by Washington, D.C. The Democratic-led ACA reshaped states’ health insurance landscapes, setting new federally mandated private market and exchange regulations and standards, while the Republican-led SBHFA and “Self-Insurance Protection Act of 2017” would allow for—if not incentivize—further outmigration of members from state authority. With the specter of the Trump administration’s promise to allow the selling of health insurance across state lines, the future of state authority over local employer-sponsored insurance markets grows ever more uncertain.20

1https://www.majorityleader.gov/2017/03/15/phase-3-legislation/

2https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/03/21/hr-1101-%E2%80%93-small-business-health-fairness-act-2017

3https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1101/text

5 https://www.sbc.senate.gov/republican//HTML/news/release2.html

6http://files.kff.org/attachment/Proposals-to-Replace-the-Affordable-Care-Act-Rep-Tom-Price

7http://www.politico.com/story/2017/03/paul-ryan-health-care-votes-republicans-235908

8http://willingness.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ABetterWay-HealthCare-PolicyPaper.pdf

9https://www.nga.org/cms/home/news-room/news-releases/page_2004/col2-content/main-content-list/governors-oppose-association-hea.html

10http://www.naic.org/documents/consumer_alert_ahps.pdf

11http://www.naic.org/documents/health_archive_naic_opposes_small_business_fairness_act.pdf

12http://global.nationalreview.com/article/208249/health-clubs-ramesh-ponnuru

13http://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/SelfInsuredPlans.pdf

14http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey

15States also maintain authority over individual purchasers and those members purchasing health insurance through state and federal exchanges. Plans offered to these members must, however, adhere to strict federal standards, unless otherwise waived by 1332 permissions. Individual purchasers were also found by the CPS to have high rates of dual-coverage sources: 58% of individuals classifying themselves as having purchased individual insurance also reported having insurance in another insurance category. For example, New Hampshire, starting in 2014, began offering Medicaid expansion enrollees premium assistance to purchase Qualified Health Plans through the state’s federally facilitated marketplace.

16Excludes any authority individual states may have on state employee purchasing

17https://www.healthcare.gov/self-employed/coverage/

1987% of firms with fewer than 200 employees were fully insured