How States Can Ensure Safety Net Hospitals Benefit from the New Medicaid Access Rule

Safety net hospitals play a vital role in serving marginalized communities, however, their efforts to advance health equity are undermined because in many states Medicaid payment rates do not cover costs. Though many states provide supplemental payments to safety net hospitals, including through directed payments, these are often not sufficient to address the payment gaps. As a result, safety net hospitals remain in chronic financial distress and operate with little to no operating capital to fund basic maintenance needs and invest in services and programs needed by marginalized communities.

Recognizing these structural payment challenges, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a new rule, “Managed Care Access, Finance and Quality”, that permits states to leverage the directed payment program to promote parity across Medicaid and commercial payment rates to strengthen support for safety net providers that predominantly serve Medicaid enrollees.1,2 This brief explores how states can leverage this new flexibility to support safety net providers.

Safety Net Hospitals Are Critical Pillars for Health Equity in Marginalized Communities

Safety net hospitals generally share several characteristics:

- Serve as key access points for marginalized populations, with 30 percent or more of the payer mix often comprised of patients who are covered by Medicaid or are uninsured.

- Some see few commercially insured patients and are often not considered as required for optimal commercial network positioning, leading to lower payment rates than other facilities.3

- Support key services that are otherwise unsupported by other facilities in their communities, including behavioral health, trauma services, and complex pediatric care.

- Serve as anchor institutions in their communities, providing jobs and community benefit programs that stimulate economic growth and well-being.4

The Medicaid Financing System for Safety Net Hospitals Has Undermined Health Equity Goals

Although safety net hospitals play an indispensable role in caring for the nation’s most vulnerable communities, these facilities are themselves fragile because of how they are paid.

|

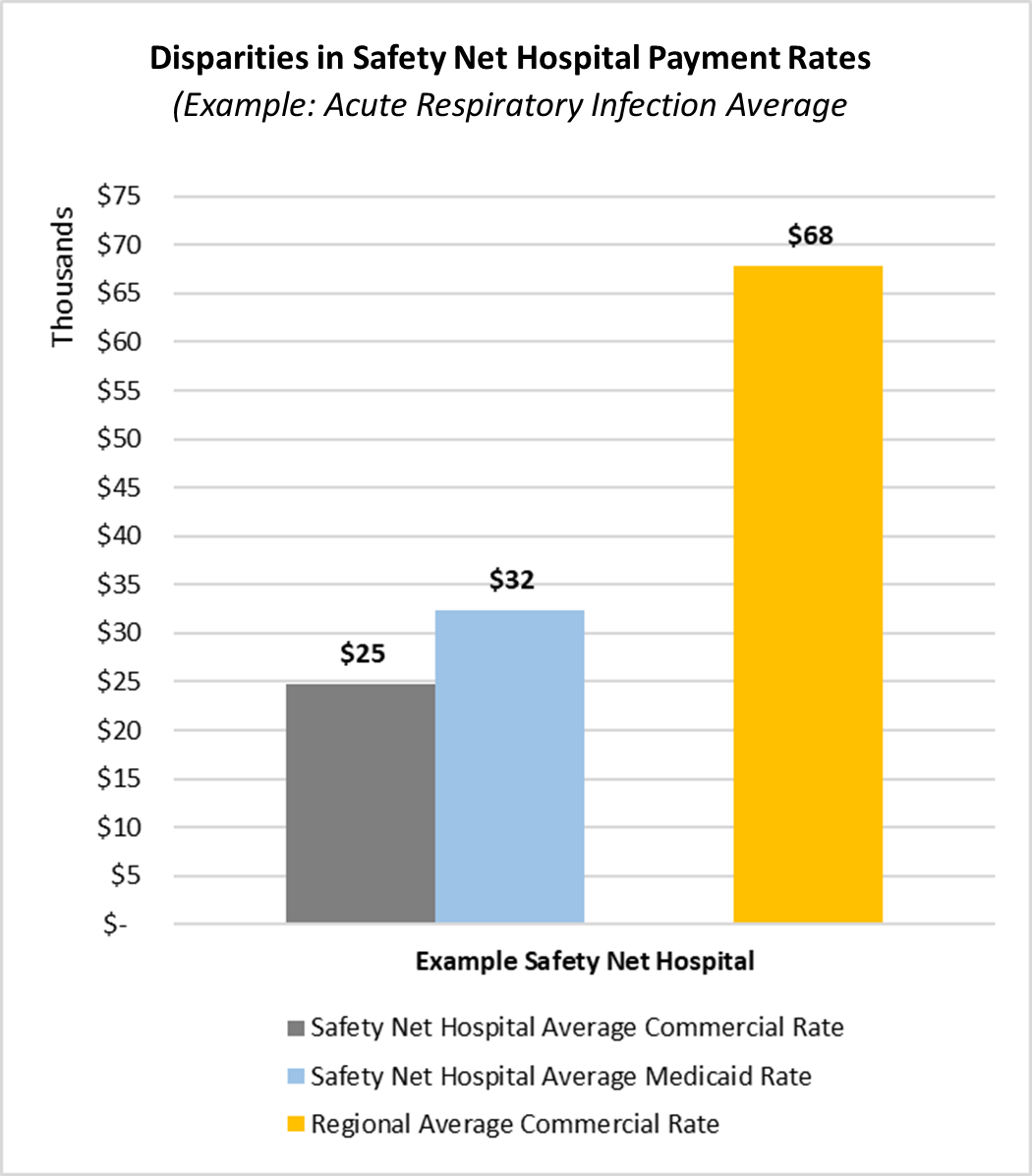

- Base Medicaid Rates Often Do Not Cover the Cost of Care: In many states, Medicaid base rates do not cover the cost of care and disparities in payment between inpatient and outpatient care incentivize hospitals to focus on increasing their inpatient case mix.5 A Manatt analysis of safety net hospitals in New York City also found significant disparities between the average commercial rate (ACR) and the Medicaid and commercial rates paid to safety net hospitals (see graph).6 These disparities can be stark depending on the service and, in some cases, the ACR can be up to seven times higher than Medicaid rates.

- Supplemental Payments Have Not Fully Addressed Payment Gaps: States have sought to address payment gaps through supplemental payments, such as disproportionate share hospital (DSH) allotments. However, DSH allotments are often insufficient and not well targeted to safety net hospitals that provide high volumes of uncompensated care.7 States have turned to the directed payment program to provide targeted rate enhancements for Medicaid managed care services and new CMS rulemaking codifies state flexibility in setting rates at levels that bring them into parity with commercial rates.

- Underpayment Has Contributed to Chronic Financial Distress: America’s Essential Hospitals, which represents many safety net hospitals nationally, reports that their members had an average operating margin of -8.6 percent in 2021.8 With little to no operating margin, safety net hospitals lack retained earnings and the ability to access capital, limiting their ability to respond to infrastructure needs and invest in new care models and programs focused on health equity.

Medicaid Managed Care Access Rule Creates New Opportunities to Advance Payment Equity

States are increasingly using the directed payment program to address payment gaps in Medicaid. Under the directed payment program, states must establish rate enhancements for a defined set of services and provider class that serve Medicaid managed care enrollees. As of October 2023, CMS has approved 1,244 directed payment proposals since the program began and CMS estimates $52 billion in annual spending for directed payments approved as of the 2022 rating period.9 A Manatt analysis of directed payment programs approved in 2022 found that 21 states have set directed payment rates at levels aligned with the ACR, allowing them to promote greater payment parity across providers serving marginalized populations.

CMS made several important changes to the directed payment program that will impact safety net hospitals, including:

- Codifies states’ ability to use the ACR as the ceiling for setting directed payment rates (effective July 9, 2024). While CMS has already approved directed payment programs that use the ACR as the rate benchmark, the final rule codifies this flexibility and enables states to use the directed payment program to promote greater rate parity across Medicaid and commercial payers.

- Allows states to set the ACR payment benchmark on a geographic basis (effective July 9, 2024). The rule permits states to establish the ACR benchmark statewide or within specific geographies of a state, rather than limiting the benchmark calculation to the class of eligible hospitals as was previously allowed. CMS highlighted the significance of this change noting that “facilities that serve a higher share of Medicaid enrollees, such as rural hospitals and safety net hospitals, tend to have less market power to negotiate higher rates with commercial plans.” As such, setting the ACR benchmark on a geographic basis “will provide States with tools to further the goal of parity with commercial payments, which may have a positive impact on access to care and the quality of care delivered.”

- Prohibits the use of separate payment terms (effective July 9, 2027). All directed payments must flow through base capitation rates for Medicaid managed care plans, rather than paid to providers through a pool of funding separate from base capitation. States will need to consider how building directed payment rate enhancements into base capitation rates might impact long-term planning for new payment models, such as hospital global budgets under CMS’ Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) model.10

- Requires new, provider-level reporting on directed payments (effective date TBD).11 Through the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System, including detailed information on individual provider payments (e.g., negotiated rates, directed payment enhancements).

- Streamlines evaluation reporting requirements (effective July 9, 2027). Including limiting formal evaluation reports to large directed payments that exceed a certain expenditure level (1.5 percent of the total managed care program). Formal evaluation reports must include at least two measures addressing performance and access, and CMS has now limited reporting to every three years, rather than annually.

Changes in the final rule present a tremendous opportunity for states to advance health equity by leveraging the directed payment program to promote greater parity in payment levels for safety net hospitals, stabilize their finances, and provide opportunity for them invest in services and programs needed by their communities.

1 “Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality,” April 22, 2024. Available at: https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2024-08085.pdf.

2 CMS has also advanced efforts to address payment equity in Medicare, including most recently in a proposed rule that would account for social determinants of health in certain ICD-10 codes, such as recognizing inadequate housing and housing instability as complications or comorbidities. The proposed rule builds on prior rulemaking that recognized homelessness as a complication or comorbidity when determining payment levels.

3 Manatt analysis of FAIR Health data, as further discussed below.

4 National Academy of Sciences, “Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity – Anchor Institutions.” 2018. Available at: https://www.nap.edu/resource/24624/anchor-institutions/

5 Deborah Bachrach, Laura Braslow, and Anne Karl, “Toward a High-Performance Health Care System for Vulnerable Populations: Funding for Safety-Net Hospitals Prepared for the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High-Performance Health System.” The Commonwealth Fund. March 2012. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2012/mar/toward-high-performance-health-care-system-vulnerable

6 Manatt analysis of FAIR Health data. FAIR Health is an independent nonprofit that collects data for and manages the nation’s largest database of privately billed health insurance claims, which includes fully-funded and self-insured plans. Citywide and Manhattan estimated commercial allowed amounts based on data compiled and maintained by FAIR Health, Inc. FAIR Health is not responsible for any of the opinions or conclusions expressed herein. Data (c) 2021 FAIR Health, Inc.

7 MACPAC, “Annual Analysis of Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments to States.” 2020. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Annual-Analysis-of-Disproportionate-Share-Hospital-Allotments-to-States.pdf

8 America’s Essential Hospitals, “Essential Hospitals Rely on Medicaid DSH.” May 2024. Available at: https://essentialhospitals.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Our-View-Medicaid-DSH-May-2024.pdf

9 “Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality,” April 22, 2024. Available at: https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2024-08085.pdf

10 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model: Hospital Global Budget Fact Sheet.” Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ahead-hgb-fs.pdf

11 Effective date will be after the first rating period following release of CMS reporting instructions.