An AI Roadmap for Academic Medical Centers’ Research Programs

Contributors: , ,

Additional authors include Jeffrey Pennington, Former Associate Vice President and Chief Research Informatics Officer, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

This is the latest edition of a Manatt Health series on AI for health systems, stemming from a recent Manatt Health white paper. Click to read the white paper and to read our previous issue. Click to read the full paper from which this article is adapted.

Research programs that are part of Academic Medical Centers (AMC) are uniquely positioned to accelerate the translation of research into clinical care. The central role of a clinician scientist in the AMC drives innovation from the viewpoint of health and disease. An organizational structure supporting basic, clinical and translational research creates a natural pipeline for innovation from fundamental biological discoveries to long-term health outcomes. Like many other factors affecting the healthcare system, artificial intelligence (AI) is fast becoming a significant disruptor to the traditional academic research model and more specifically, the translational research model which focuses on the translation of scientific discovery and innovation to clinical and health impact. Below, we present a framework outlining key steps AMC-based research organizations will need to take to prepare for AI and develop their programs accordingly.

Framework for AI Within an Academic Research Environment

AMC-based research organizations have limited resources. It’s critical that they have a clear understanding of what their capabilities are, how AI can align with their broader strategic goals and imperatives and what role they want to have in the AI industry.

There are three general approaches worth consideration. Most AMC-based research organizations will have a portfolio of AI initiatives that span these approaches and will need to determine how they want to balance investments to support each:

- Productivity: Focus on AI-driven automation to streamline common research functions that are time consuming (e.g., AI-enabled clinical trials, data extraction and organization, identification of similar studies and access to their related publications). This approach may provide limited commercial opportunity but broad benefit to the research staff. There are fewer challenges with these opportunities as they would have less direct impact on clinical care and can be organized and delivered as part of a research organization’s infrastructure support. This is likely a combination of “buy and build” strategies.

- Destination clearinghouse for new AI technology adoption: Create a platform to test new AI-based solutions within the healthcare environment and/or modify new technology for adoption within the health system. Again, there may be modest commercialization opportunity, but this approach could help maximize an organization’s ability to leverage new AI innovations and limit adoption risk. The platform would likely require partnerships with peer institutions or others who can help provide sufficient data to support broad use cases and close collaboration between the research and clinical care organizations to facilitate and oversee translation into the care models. This is a “buy and modify” strategy.

- Creator: Become an incubator for novel AI innovations. Although the most complex and challenging approach, it creates the greatest opportunity for industry impact and commercialization. This would require industry partnerships and significant governance to manage risk. This is a “build” strategy.

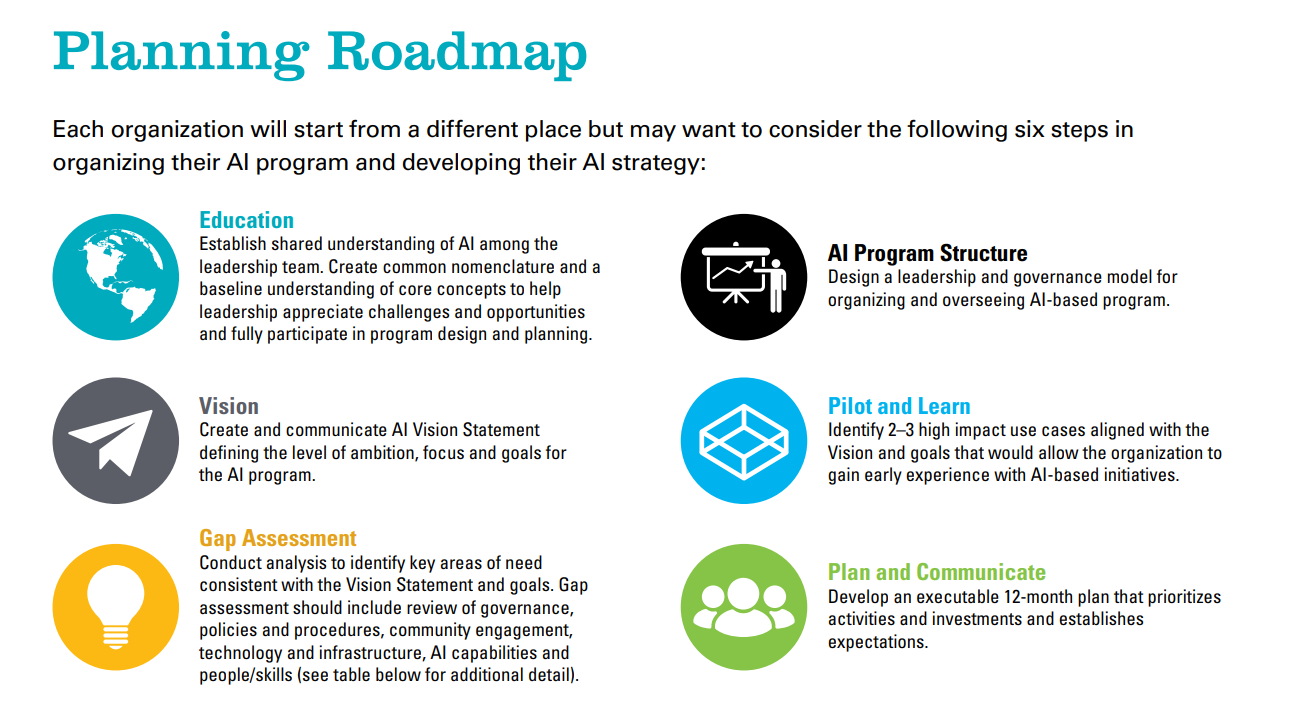

Planning Roadmap

Each organization will start from a different place but may want to consider the following six steps in structuring their AI program and developing their AI strategy:

Conclusions

Imagine a future where AI can help providers deliver better care to patients in the most resource constrained health systems. Over 1,300 Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) provide front line care to rural communities in our country. By law, these hospitals only receive supplemental funding if they limit lengths of stay to 96 hours, have fewer than 25 patient beds and provide 24/7 emergency department care. These conditions require them to operate under extreme financial constraints. Advanced Practice Providers such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists often provide direct service to patients. AI has the potential to extend the ability of these skilled professionals to perform advanced health screening, provide a broader range of diagnostic services, access critical clinical expertise when needed and offer aspects of specialty and acute care otherwise unavailable to these communities. AMCs are uniquely positioned not only to teach medical students but also teach AI systems to bring the cutting-edge expertise of their care providers to the dedicated professionals working hard to improve the health of patients at CAHs, public hospitals and beyond.

Using AI to create needed efficiencies for our providers and AMC-based research organizations, help lower costs, and to improve access, consistency and quality of care, will result in a more equitable and sustainable system of care. There are many challenges to organize, fund and manage effective AI programs in an AMC environment, but the potential rewards are great and the risks of missed opportunity and declining viability associated with inaction are compelling.