The Limitations of Price Transparency

In a recent , the Administration doubled down on price transparency as a policy vehicle intended to curb health care spending. There are two potential pathways for price transparency to impact aggregate health care spending. First, what has historically been an opaque negotiation process including contractual nondisclosure agreements between payers and providers could become less secretive, allowing payers to compare the rates that they negotiate to those of other insurers. The second pathway would have patients shopping for medical procedures based on unit prices. This second pathway - specifically, the ability of price shopping by consumers to have a meaningful and material impact on the nation’s total health care spend – is the principal focus of this essay. The assumed relevance and benefits of price transparency for individual consumer decision-making has its roots in classical economic theory, but idiosyncrasies unique to health care make the realization of those benefits far more complicated.

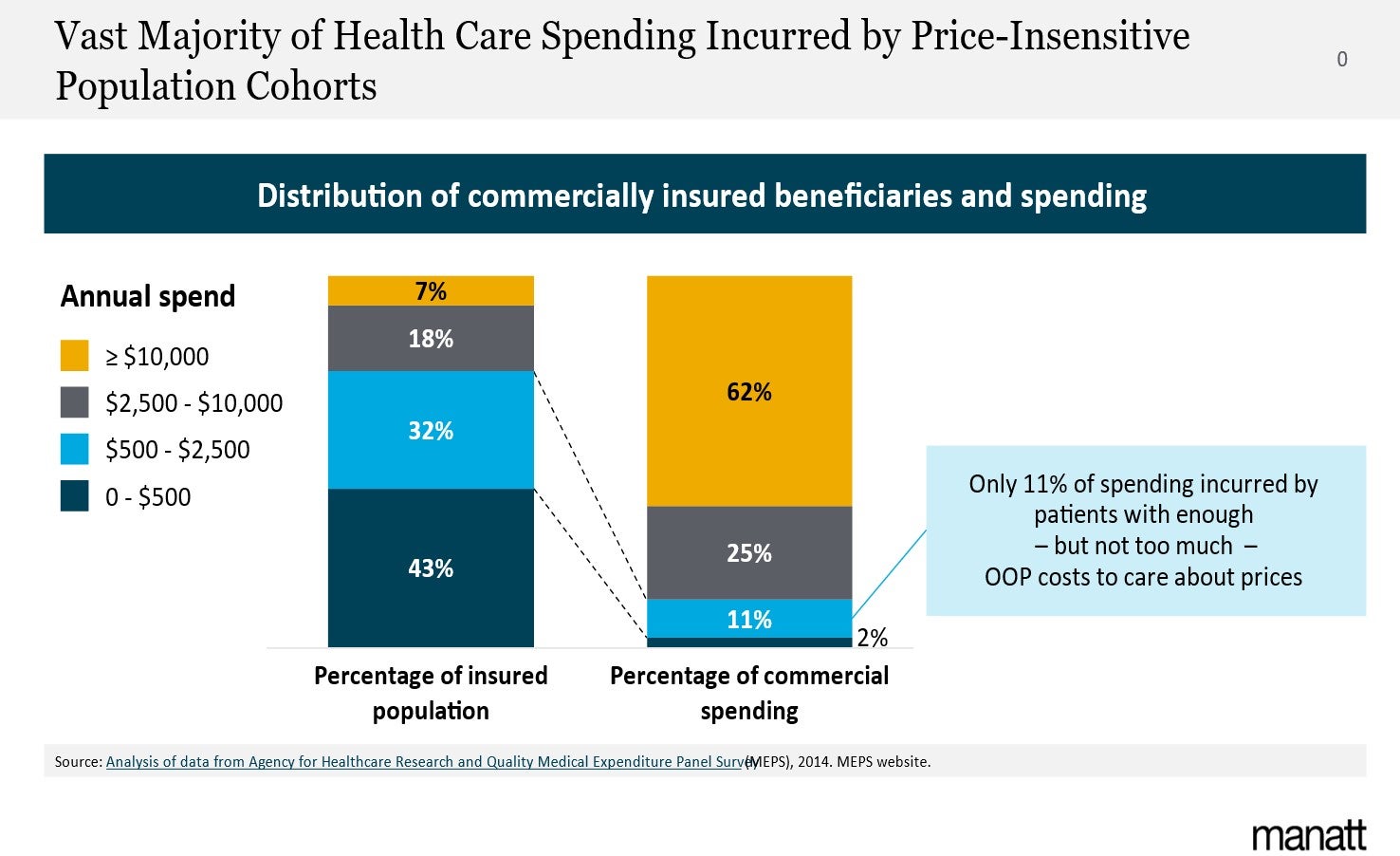

At the core of the ineffectiveness of health care price transparency in reducing aggregate health care costs is the distribution of spending across any population in the U.S. or Europe. It can be a company, a county, or a country – the distribution is always the same: 80% of the spending is incurred by 20% of the population, and that 20% is so expensive that the overwhelming majority of their cost is covered by insurance. Even more telling, 50% of any population’s spend is incurred by only 5% of the people, most of whom incur tens of thousands of dollars in medical costs. No meaningful price sensitivity is possible without bankrupting the patients’ families.

A close look at Exhibit 1 illustrates why price transparency – when applied to individual patient choice – can only have a very limited impact on overall health care spending. The vast majority of spending is incurred by patients whose episodes of care are far too costly for price sensitivity to exist. Only 11% of total spending is incurred by patients who meet their insurance deductible but do not exceed their maximum out of pocket exposure. Once the maximum out of pocket responsibility is exceeded, the prices no longer matter. With only 11% of all spending occurring in what could be considered the “price elasticity window,” meaningful savings occurring from price transparency are virtually impossible. Some influence over patient choice inside the elasticity window is possible, and may benefit individual consumers in a particular health care transaction, but the magnitude of such an impact on overall spending will be quite small. The lack of traction for patient-level sensitivity is underscored by , where a price transparency website using accessible information saw very little use by consumers.

Counterintuitively, individual patient price elasticity of demand in health care – if it existed – would risk even higher spending. In a study conducted during my tenure leading the Vizient Research Institute, we discovered that cancer episodes treated within a single health system cost 20% less than clinically equivalent episodes treated by a fragmented group of providers in multiple health systems. Having patients shop for individual services based on unit prices – to the extent that it results in fragmentation of episodes of care – would actually be economically counter-productive.

The distribution of spending across any population – dictated by epidemiology, not economics – means that price transparency cannot have a material impact on overall spending through individual patient choice. The risk of even higher costs arising from the fragmentation of complex episodes of care suggest that the absence of price elasticity of demand may actually be fortuitous.

A potential impact of price transparency outside of patient choice is the opportunity for insurers or payers with smaller market share to see provider payment rates negotiated by payers with more local market clout. There is ample evidence of wide variation not only between markets but within markets for identical services. Patients covered by different insurers often pay markedly different prices for the same services rendered by the same providers. While individual patient price sensitivity has extremely limited applicability, the sometimes enormous variation in prices within a given market lead to the belief by many that transparency across payers could lead to more rational prices. As intuitive as that result appears, however, it is also possible that transparency could have a chilling effect on provider discounting. Providers may be reluctant to offer significant discounts to payers with larger market share if they expect those payment rates to eventually be extended to payers with less volume.

It is important to note that nothing herein is intended to imply that price transparency is a bad idea. By lifting the veil from payer/provider negotiations, the possibility exists for contractual payment rates to narrow both between and within markets, but even that would have only a marginal impact on overall health care spending. Examples of smaller payers or self-funded employers realizing not inconsequential savings as a result of local price transparency have been noted, but the impact of such savings on aggregate U.S. spending has been negligible. Of the nearly $5 trillion in annual health care spending, 30% is covered by private insurers, with roughly two-thirds of that accounted for by top ten insurers. Smaller private sector insurers, who would benefit most from price transparency, account for only 10% of total spending. Even if transparency resulted in an immediate 10% reduction in prices for all of those insurers, the impact on aggregate spending would be only 1%. If discounts to larger payers were reduced out of fear that they would extend to smaller payers, spending could actually increase.

When contemplating the potential impact of price transparency on health care costs, it is important to distinguish between individual transactions and overall aggregate spending. While transparency may enable an individual patient to reduce their out of pocket cost for a particular service or procedure, the cumulative impact of patients shopping based on price will be minimal. Similarly, while price transparency may enable a small insurer or a self-funded employer to reduce their expenditures, the overall impact on aggregate national spending will be quite small. From virtually every angle, price transparency can only be expected to have a marginal impact on overall health care spending.

For more information, please feel free to reach out to .