State Telehealth Laws and Medicaid Policies: 50-State Survey Findings

Introduction

The use of telemedicine services is growing nationwide as providers and payors seek to improve access and better manage patient care, while reducing health care spending. State laws and Medicaid1 policies related to reimbursement, licensure and practice standards are rapidly evolving in response to the proliferation of technology and the growing evidence base demonstrating the impact of telemedicine on access, quality and cost of care. Some states have been proactive in encouraging the use of telemedicine as a means to enhance services in rural areas, increase access to care for members with complex conditions, and reduce costs associated with unnecessary emergency department visits.

In light of this rapidly changing landscape, Manatt Health has conducted a 50-state survey of state laws and Medicaid program policies related to telemedicine in the following key areas:

- Practice standards and licensure

- Coverage and reimbursement

- Eligible patient settings

- Eligible provider types

- Eligible technologies, and

- Service limitations.

Based on survey results, we classified state telemedicine policies as “progressive,” “moderate,” or “restrictive” across each of these categories. (See Table 1 “State Telemedicine Policies Classification Table”.)

The survey is intended to inform health systems and providers, state policy makers, and technology companies, regarding state-specific policies for providing health care services via telemedicine generally, and for Medicaid beneficiaries specifically. Survey results are current as of April 2018.

Key Findings

Nearly all state Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for some telemedicine services. Most states allow several types of providers to administer care via telemedicine, and few limit the specific types of services that can be provided through these modalities. While there has been notable progress, some restrictions on the provision of telemedicine services for Medicaid members remain.

Patient’s home as a site of service. The home is a critical access point for telemedicine services; it enables patients in rural areas to connect with their providers, and enables health systems to increase clinic capacity by conducting many types of routine follow-up or other visits remotely. Twenty six states provide reimbursement for telemedicine services delivered in a patient’s home.2

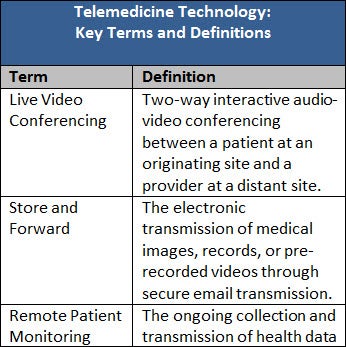

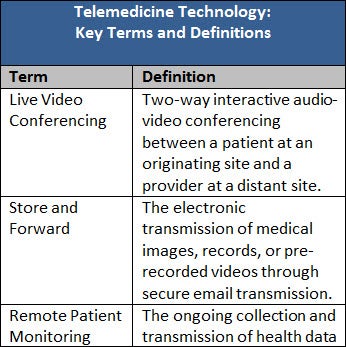

Patient’s home as a site of service. The home is a critical access point for telemedicine services; it enables patients in rural areas to connect with their providers, and enables health systems to increase clinic capacity by conducting many types of routine follow-up or other visits remotely. Twenty six states provide reimbursement for telemedicine services delivered in a patient’s home.2- Reimbursement for technologies beyond live video conferencing. Nearly all state Medicaid programs provide coverage and reimbursement for live video conferencing, but fewer states reimburse for telemedicine technologies beyond live video, such as store and forward, remote patient monitoring, or email and phone. Twenty nine states are reimbursing for at least one method in addition to live video, and sixteen states are reimbursing for three of the four different telemedicine technologies (most states do not reimburse for care provided via email and phone).

- Physician-patient relationship. Nine states require a provider to have an established relationship with a patient before they can connect and provide them with care via telemedicine.3 For example in Mississippi, a “valid physician-patient relationship,” which includes a prior physical exam, must exist in order to provide care via telemedicine. Medicaid policies that require such a relationship claim to protect patients but also inhibit new market entrants that offer urgent and primary care services from serving the Medicaid market.

- Frequency limits. Nine states place limits on the frequency with which Medicaid patients can receive care via telemedicine within a given timeframe. For example, in Georgia, hospital services are limited to one telemedicine visit every three days, and nursing facilities are restricted to one telemedicine visit every thirty days.

- Geographic limits. Nine states place geographic restrictions on telemedicine encounters; their Medicaid policies limit reimbursement based on where a patient or originating site provider and the distant site provider are located. For example in Indiana, the state only reimburses for telemedicine services when the hub and spoke sites are greater than twenty miles apart.4

Implications

A growing body of evidence suggests that telemedicine will be critical to delivering health care in the future, and state Medicaid policies are evolving—in some states more quickly than others—to accelerate adoption of telemedicine models. As technology advances and the evidence base for telemedicine expands, state policy will continue to evolve to integrate telemedicine into payment and delivery reforms that support overarching program objectives related to access, quality, and cost of care.

For more information on telehealth, see our June “Health Update” article, “Telehealth: From Competitive Advantage to Strategic Imperative” and our July Compliance Today article, “Telehealth: A New Frontier for Compliance Officers”.

Note:

This analysis was conducted for Insights@ManattHealth, a subscription service that provides a searchable archive of all of Manatt Health’s content and features premium content that is available only to subscribers. In addition to access to state profiles providing detailed information on state laws and Medicaid program telemedicine policies, subscribers have access to: other 50-state surveys; weekly updates of key federal and state health policy activity; detailed summaries of federal Medicaid, Medicare and Marketplace federal regulatory and sub-regulatory guidance; and much more. If you are interested in learning more, please contact Patricia Boozang at PBoozang@manatt.com.

Table 1: State Telemedicine Policies Classification Table

1Unless indicated otherwise, all references to state Medicaid programs refer to Medicaid FFS. Select Medicaid managed care plans from some states were reviewed as part of this survey effort. Generally, Manatt found that these select Medicaid managed care plans encouraged the use of telemedicine and considered Medicaid FFS policies as a foundation for reimbursement.

2Some of these twenty six states place limitations on reimbursement when home is the originating site. For example, in New York the home is only an eligible site of care for remote patient monitoring services. In states that had no originating site restrictions or limitations, Manatt assumed that the home is an eligible site for reimbursement.

3In some of these states, if specific conditions are met the required provider-patient relationship may be established via telemedicine.

4The following providers are exempt from distance requirements in Indiana: federally qualified health centers, rural health clinics, community mental health centers, and critical access hospitals.

**********

Correction: A previous version of this newsletter indicated that Colorado’s Medicaid program reimbursed for telehealth services provided via store and forward and email/phone, but Colorado does not reimburse for services delivered via those modalities.