Affordability and Policy Implications of the BCRA

Affordability and Policy Implications of the BCRA

The Senate is poised to vote today on a motion to proceed (MTP) to debate on repealing and possibly replacing the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The MTP allows the Senate to consider the House repeal and replace bill, the American Health Care Act, and then propose a “substitute.” If the motion is successful, it is unclear at this time what the Senate substitute bill would be. There are three potential options:

- The July 20 version of the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) which includes a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) score;

- An updated version of the 2015 repeal and delay bill, which has an updated CBO score; or

- A modified version of the BCRA, with additional changes to accommodate members’ concerns with the latest version of the BCRA.

Given the continued importance of the BCRA to the ongoing repeal and replace debate in the Senate, in this week’s “Manatt on Health,” we update and reissue our two prior newsletters unpacking the implications of the BCRA.

Can People Losing Medicaid Under BCRA Afford Marketplace Coverage?

By Deborah Bachrach, Partner | Patricia M. Boozang, Senior Managing Director

A significant area of concern among senators and governors in Medicaid expansion states is the loss of coverage under the BCRA for those who have it today under the ACA and the unaffordability of the new BCRA coverage options for low-income people. The July 20 CBO score estimated that the BCRA would lead to substantial loss of health insurance coverage, increasing the uninsured number by 22 million in 2026 compared to current law. The coverage loss is driven primarily by the BCRA's phase out of the enhanced federal Medicaid funding under the ACA that allowed 31 states and the District of Columbia to expand Medicaid coverage to 14 million people with incomes below 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). The phase down and eventual elimination of the enhanced funding will require many (perhaps most) expansion states to end expansion, if not in 2021 when the phase down begins, certainly by 2024 when the enhanced funding is eliminated entirely. Whether states end expansion before or during the funding phase down, ultimately the result will be the same: very low-income parents and other adults will lose Medicaid coverage.

The Senate bill provides that individuals with incomes below 100% FPL may access subsidies to purchase insurance through qualified health plans (QHPs) in the Marketplace, filling a gap in the ACA that provided subsidies only to those with incomes above 100% FPL. (The ACA anticipated that the expansion would be implemented in all states; but, the expansion became voluntary after the Supreme Court’s decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius). BCRA proponents have suggested that the new subsidy construct will be a viable replacement for Medicaid coverage and indeed a source of coverage for low-income adults in non-expansion states. In this issue of “Manatt on Health,” Manatt estimates out-of-pocket costs under the BCRA to test coverage affordability for low-income families, many of whom are covered under the Medicaid expansion today.

Like the ACA, the BCRA proposes that Marketplace enrollees pay a portion of their incomes (adjusted by age) toward the cost of a benchmark plan, with the federal government paying the difference in the form of tax subsidies.1 However, the BCRA makes an important change to the benchmark plan by lowering the plan’s actuarial value or AV (the proportion of covered services for which the plan must pay) to 58%;2 under current law the benchmark plan has a 70% AV. Further, the bill eliminates the cost-sharing reduction subsidies that are currently in place to ensure affordability of out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance) for those with incomes below 250% FPL who purchase Marketplace coverage.

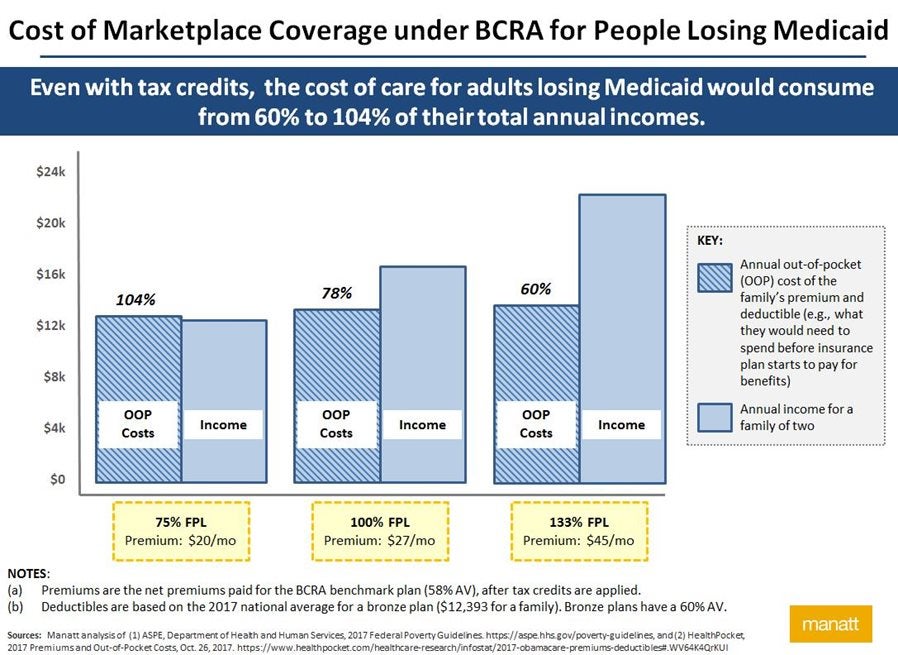

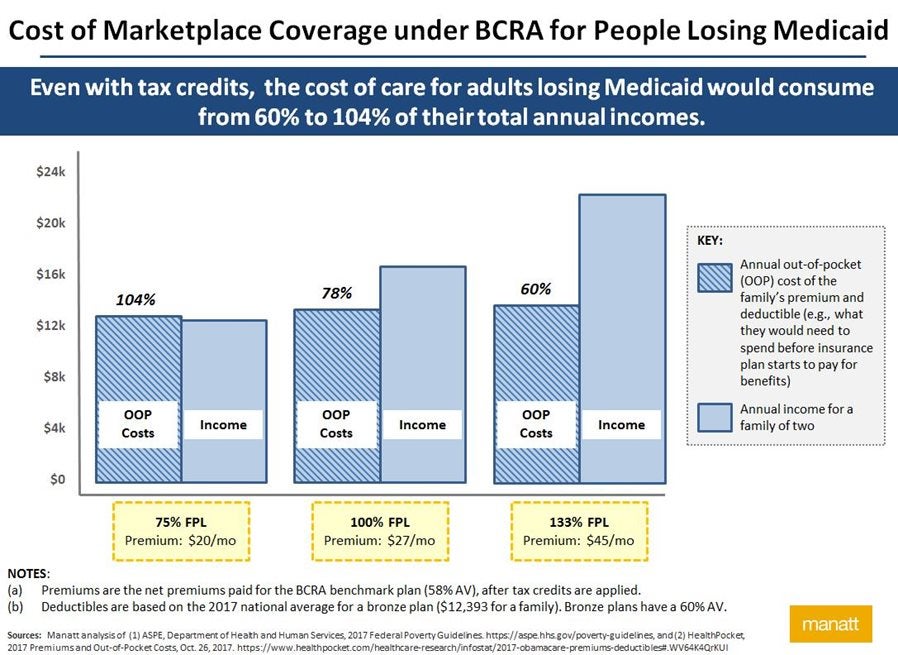

To assess affordability of coverage for low-income people under the new BCRA subsidy approach, Manatt considered premiums and deductibles under the new BCRA benchmark plan as a percentage of family income. As the chart below shows, under the BCRA, a family of two with an income below 133% of the FPL would be required to pay more than half of its annual income toward healthcare costs before its insurance plan would begin to pay for most covered services. For example, the deductible and premiums for a family of two earning $16,240 a year (100% FPL) would amount to more than three-fourths (78%) of that family’s total annual income.

Responding to expansion states’ coverage affordability concerns, a number of ideas have been floated to mitigate the high cost of Marketplace coverage under the BCRA:

- CMS Administrator Verma has suggested that expansion states might be permitted to use funds from the BCRA individual market stability pool (funded at $180 billion for the period from 2019 through 2026) coupled with funds secured through a Section 1115 waiver to further subsidize out-of-pocket costs for low-income people covered in Medicaid today.

- Media reports last week refer to a proposed $200 billion fund to be added to the BCRA for states that expanded Medicaid; as of this writing, it is unclear whether this fund would be used to fund the waiver approach, or would be over and above the waiver option. Reports suggest that the new pool would be funded by leaving in place the ACA net investment income tax and Medicare surtax and would be distributed in the out years of the BCRA when the enhanced funding for Medicaid expansion is fully eliminated. Notably, this new pool of funding is not reflected in the Senate’s latest BCRA language released on July 20.

- Over the weekend, the “Graham Cassidy” proposal emerged, which would give states a federal block grant that would replace federal funding for Medicaid expansion, tax credits, and cost-sharing reduction subsidies. States would have flexibility to use these funds to “pay for healthcare costs” for people in their states. There are few additional details on the proposal, including the program and spending requirements that would be attached to the block grant.

Each of these proposals shares a common theme: knitting together multiple pots of federal funding, some of which appear time limited. There are significant questions about whether sufficient BCRA pool and waiver funding could be patched together to implement and sustain in all 31 expansion states a broad-based coverage solution that is comparable in benefits and affordability to coverage under the ACA. Additionally, current law ensures enhanced federal matching funds for all states that expand Medicaid coverage, whereas waivers are time limited and subject to the discretion of the CMS Administrator, and block grants shift spending and enrollment risk to states for healthcare spending. In the case of Graham Cassidy, the risk shift to states would be for both Medicaid and low and modest income residents with incomes above Medicaid levels who rely on ACA tax subsidies and cost-sharing reductions today. Both of these proposals create new processes, uncertainty and financial risk for states. With respect to the waiver proposal, whether the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) would find waivers to be budget neutral to the federal government and how they fit into the capped Medicaid funding structure advanced by the BCRA adds additional levels of complexity and uncertainty. Another major open question is whether the waiver option would be available to non-expansion states that might want to wrap Marketplace costs for their low-income residents.

Despite the lack of details around these proposals, it is clear that the stability pool is intended for multiple purposes (see below for more details), including generally stabilizing coverage in the non-group market, and that both the stability pool and the $200 billion pool are time-limited, making the long-term sustainability of the funding sources for the affordability proposals uncertain at best. Finally, if the end goal of these proposals is to shift people currently covered by Medicaid to Marketplace plans with comparable affordability and benefits, they are likely to cost the federal government more than coverage through Medicaid, which has been well-documented as a less costly way to provide coverage. This raises the most puzzling question related to these proposals: Why replace an existing system that works reasonably well with a new, temporary patchwork of pools, grants and waivers that costs more and falls short of what the Medicaid program already does?

1If an enrollee chooses to purchase a non-benchmark plan, they still receive the tax credit they would have received for the benchmark plan. In this situation, the enrollee would be responsible for the difference between the plan’s premium and their tax credit amount.

2A plan’s AV signifies the value of the plan, or the percentage of expected costs covered by the insurer. For example, a low AV plan has lower premiums, but is also of lower value meaning that the individual would be expected to pay high out-of-pocket costs.

Key BCRA Policy Concerns

By Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, Managing Director | Patricia M. Boozang, Senior Managing Director | Cindy Mann, Partner | Ari Levin, Manager

Republican senators from both the moderate and conservative wings have expressed concerns with the released versions of the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), leading to complications with passage. The most significant areas of concern among senators and their governors include:

- Loss of coverage and unaffordability, as described above;

- Insufficient (and double-counted) stability funding for the individual markets;

- Significant cuts to Medicaid; and

- The Cruz Amendment.

Below we describe each of these concerns in more detail.

Competing Priorities for Limited Stability Fund Dollars. Like the American Health Care Act (AHCA), the BCRA included State Stability and Innovation funding intended to help stabilize state individual insurance markets. The July 13 and 20 versions of the BCRA included $50 billion in short-term funding that would go directly to insurers and $132 billion in long-term funding that would go to states ($70 billion more than the original version of the BCRA released on June 26). However, the additional $70 billion was promised for a number of different purposes, including briefly for insurers who chose to offer noncompliant plans under the Cruz Amendment (described in more detail below and dropped in the July 20 BCRA version) and to help make coverage more affordable for individuals (a priority for moderates concerned with coverage issues). Still others expected the funding to be used for state reinsurance programs. There were already concerns about the efficacy of the funding to solve any one of these issues; the multiple claims on the funds established to alleviate anxieties across the Republican Caucus only elevated the concerns. See the table below for more information about the funding sources in the BCRA.

Significant Cuts to Medicaid. Like the House version of repeal and replace, the BCRA would end the enhanced federal funding for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion; the BCRA would phase out the enhanced match over three years starting in 2021. And like the House bill, the BCRA would limit federal spending through the imposition of per capita caps, with the caps slated to grow by no more than general inflation beginning in 2025. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the Medicaid provisions in the bill would result in reductions in federal Medicaid spending in excess of $756 billion relative to current law. The cuts to Medicaid funding and the related impact on coverage are among the most controversial and troubling provisions of the BCRA for moderate Republican senators and for governors across the political spectrum. While primary among these concerns is loss of coverage for 15 million people, other issues generated additional, significant opposition:

- The “Cost Shift” to States. The $756 billion in cuts to Medicaid would cause some states to lose more than a third of their federal Medicaid funding. Those reductions would grow over time, and the caps would shift all risks of higher healthcare costs onto states. (See Manatt’s analysis on the financial impact of the BCRA for states.) States would be faced with difficult choices necessary to respond to this level of spending reduction—including eliminating expansion, cutting eligibility and benefits more broadly (e.g., for children, pregnant women, the elderly and people with disabilities), and reducing provider reimbursement, putting access to care at risk—all cause for serious concern among Republican senators and governors including Governor Asa Hutchinson (R-AR), who commented on an earlier version of the Senate plan saying: “We can’t just have a significant cost shift to the states because that’s something we cannot shoulder.”

- The Opioid Crisis. States continue to grapple with the opioid addiction epidemic, and governors and senators in states most impacted by the crisis are deeply worried about the loss of Medicaid expansion funding given the crucial role Medicaid plays in substance use screening, diagnosis, treatment and recovery. The BCRA’s $45 billion fund from 2018 to 2026 to support state grants for substance use treatment did little to assuage these concerns given the time-limited nature of the funding and its likely insufficiency to cover all states’ needs as compared to the current law’s funding for comprehensive coverage through Medicaid expansion. Senator Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) has been particularly vocal on this issue: “I have serious concerns about how we continue to provide affordable care to those who have benefited from West Virginia’s decision to expand Medicaid, especially in light of the growing opioid crisis. All of the Senate healthcare discussion drafts have failed to address these concerns adequately.”

- Flexibility. From the outset of the repeal and replace debate, Republican governors have been calling for greater flexibility with regard to Medicaid program design and administration. In the July 18 bipartisan governors’ letter to Senate leadership, governors cited “state flexibility” as one of four guiding principles for healthcare reform, and noted their concerns that neither the House nor the Senate’s repeal and replace bill contained any meaningful provisions related to new state flexibility for innovation. In his recent New York Times op-ed, Governor John Kasich (R-OH) said, “[T]he Senate plan was rejected by governors in both parties because of its unsustainable reductions to Medicaid. Cutting these funds without giving states the flexibility to innovate and manage those cuts is a serious blow to states’ fiscal health.”

Cruz Amendment. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) sponsored an amendment designed to shore up conservative support by allowing insurers that sold ACA-compliant plans to also sell non-compliant plans with limited benefits and medical underwriting. The amendment encountered strong resistance from moderates and stakeholders, including the two leading insurer associations, which said bifurcating the market would make coverage unaffordable for many people with preexisting conditions and called the amendment “unworkable in any form.” In the end, Senator Cruz also lost the support of his co-sponsor, Senator Lee (R-UT), when Senator Cruz tried to allay other senators’ concerns, including those of Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA), by making the regulated and deregulated business subject to the ACA’s “single risk pool” requirement. Despite Senator Lee’s concerns, there were considerable questions about whether the vastly different types of business could be pooled together in any meaningful sense. Likely in part because the amendment would be so difficult for the CBO to score, the latest version of the BCRA released on July 20 no longer includes this amendment.