So You Want Music in Your Video: 5 Things to Remember so You Don't Get Sued

- So You Want Music in Your Video: 5 Things to Remember so You Don't Get Sued

- Streaming Can EXPAND Artist Revenues—BandPage & Rhapsody Point the Way

- Media's Online-Offline Nexus: Connecting Virtual, Physical Worlds

- Restoring the Value of Art and Enforcing Creator Rights—Unapologetically

- Digital Music Updates

In this edition, we focus on the world of music, exploring the opportunities for artist-fan engagement, examining the conflicts between piracy and artist livelihood, and, for creators, providing guidance on navigating the use of music in your own work.

So You Want Music in Your Video: 5 Things to Remember so You Don't Get Sued

By David Rappaport and Jordan Bromley

This article was originally published in Newsweek.

Last month we received a call from a woman who made an unassuming video of her daughter's wedding and added her favorite song as the musical bed. She was frightened, a little angry and perplexed by the copyright infringement letter she received from a major music publisher.

"All I did was make a video for myself. I'm not selling it!" Unfortunately for her, she used a song that was owned by someone other than her…in this case, a music publisher that was intent on enforcing its rights.

Granted, most music publishers don't go after people with aggressive letters, but it is no secret that video creators are constantly surprised by rightful infringement claims from songwriters, publishers and record labels. Most people don't know the correct way to "clear" music in their videos. Some don't understand that there is no "safe harbor" for use of music in a video. No matter how short, no matter how limited the views, no matter how you credit the creators…if you use it, and you don't clear it, you're an infringer.

Here are some tips to save you an unpleasant surprise.

1. There are two "sides" to every song—the musical composition and the master recording. Think of the composition as the sheet music, the song that you sing. Think of the master as every time you record that song. The composition is eternal, and the master is the recorded moment where you perform that eternal work. You HAVE to "clear" both.

2. The "clearance" is called a "synchronization license" ("synch license" for short) since you are "synchronizing" the audio to the video. Boiled down, you need a synchronization license from the composition owner AND the master owners (it can be several people if various people wrote the composition/own the master) before you share your video with the world. It doesn't matter if you're making money or not, and it doesn't matter how little of the composition and master you use in your video; if it's a recognizable part of the composition, don't take a risk. If it is ANY part of the master recording, you need to clear it.

3. Become familiar with the concept of "Most Favored Nations" (or "MFN" for short). This is a way the various owners of the music make sure no owner is earning more on the license than any other owner. It is also a way to legally "game" the clearance system. If you can find one sympathetic owner to grant a less expensive or gratis license, you can use that to get everyone else to come in on an MFN basis with the first licensor. This takes some finesse and knowledge of the major publishers and labels that own a majority of the world's musical content.

4. You don't need a license from every co-owner of the composition or master. There is a more complicated way around a stubborn songwriter, publisher or record label in the rare instances where there are co-owned masters. Put simply, under the real property concept of joint tenancy, one owner can grant a nonexclusive license for 100% of the work, provided that the other owners are paid their respective portion of the income made from the license. If you need that license—and you can't get it from all owners—this is a way around replacing the song.

5. Don't forget about public performance licenses! If you're exhibiting the video on your own website, you need to obtain a public performance license in addition to the synch license. This affords you the right to play the music in a public venue…in this case, on a public facing website. For more information, visit www.ascap.com, www.bmi.com, www.sesac.com, http://globalmusicrights.com

Streaming Can EXPAND Artist Revenues—BandPage & Rhapsody Point the Way

Conventional wisdom is that subscription music streaming services like Spotify—which now drive more overall music revenues than direct downloads—drive significantly less revenues to artists themselves. That's true if streaming service revenues are considered in isolation.

But, the promise of streaming is very different, i.e., that subscription services can actually catalyze EXPANDED artist revenues by opening the door to new fans (expanded audience) and deeper direct fan-artist engagement (and all of the myriad new revenue opportunities that go with it). I wrote about this previously at length in Billboard in an article titled "Why This Venture Capitalist Is Optimistic About the Music Business"—and called this a new "community-based" business model for artists in which each individual revenue stream today may be significantly less than they were in the past, but taken together, they ultimately may drive greater overall revenues.

The problem is that few, if any, major streaming services embraced those possibilities. Until now.

In a major shift—important to understand, embrace, and expand into other major music subscription services—oft-overlooked granddaddy streaming service Rhapsody just announced a significant new strategic partnership with artist-fan engagement service BandPage to bring unique fan-artist engagement offers (like VIP meet-and-greets) into the overall streaming experience. This means that as I listen to the new songs by MUSE on Rhapsody (a service I still use today because it is the offspring of the service I helped introduce a decade ago as president & chief operating officer of Musicmatch) I will receive notifications of upcoming shows near me in real time (and special offers related to it). And, that's just one obvious example. It's up to artists, their representatives, and the services themselves to explore all tantalizing possibilities. Rhapsody's treasure trove of data about all of my listening over the years—and BandPage's artist toolset—make this all possible.

Subscription music streaming services are today's reality. Great for music lovers with the "all-you-can-eat" model and access to 30+ million songs. I have lived this myself for a decade because I listen to music virtually 24/7. But, these oft-maligned services also have the potential to drive expanded engagement in music overall, and expanded revenues to artists by connecting them directly with a deepening passionate fan base (who will happily fork over more money for the promise of deeper access to, and engagement with, the artists they love).

As I said then (in my Billboard article), I'll say it again now. I am an optimist about artist monetization possibilities in our brave new digital world. Pessimism breeds only resentment of changing times and suffocates those possibilities . . .

Media's Online-Offline Nexus: Connecting Virtual, Physical Worlds

This article was originally published in Wired Insights.

We always write and read about the virtual world of online media in Wired, but not so much about the physical world of live media experiences. But the virtual and physical worlds absolutely should be connected in this increasingly disconnected world in which we can all communicate with one another, but rarely really meaningfully communicate and feel that we are part of a real community.

First, let's take film. Why do we still go to the movies, still fight traffic and the throngs, and still pay for expensive popcorn when we can watch from the quiet solitude of our own homes? Precisely because we are social creatures, and we don't always want quiet solitude. Have you experienced watching a thriller in a theater and, then, the same thriller at home? It's an entirely different experience due to the entirely different energy generated in the big communal room versus your smaller private room. It's simply more thrilling to watch a thriller with others who gasp when you gasp and jump when you jump.

How about music? Music business models are disrupted. Traditional revenue streams are drying up. All doom and gloom, right? Wrong. Music festivals are sprouting all over. Why? Because these festivals become so much more than the music itself. The music draws you in, but the real magic comes from the like-minded community and shared immersive experience created during that moment in time. The Bonnaroo festival perhaps best embodies these possibilities. Yes, Bonnaroo is an extremely lucrative business. But it is also absolutely an authentic physical community experience where the audience bonds over music, literally (frequently, very literally) connects with one another, and creates a magical moment in time.

So, how many online movie and music services get it right and fully embrace their physical alter ego? Not many.

As examples, take leading online music purveyors Pandora and Spotify. These pure-play companies suffer from increasing competition from industry behemoths (like Apple and Google), as well as challenging artist relations and costs of goods (primarily ever-increasing music licensing costs). What's a Pandora or Spotify to do amidst these daunting realities? Perhaps differentiate themselves from all others by bringing their customer experiences into the physical world of music festivals. Expand their connection with their virtual customers. Deepen them. Create a real differentiated and fully realized community. The Pandora "Unboxed" Music Festival! Gold Jerry, Gold! Again, the online community drives offline success—and then the offline, more deeply connected community drives further online success.

But, don't stop there. Music festivals harness the energy from your magical weekends. That energy typically dissipates when the weekend is over. Mobilize that passionate community you created. Continue its life and extend that energy online. Continue the "conversation" beyond the physical venue itself via virtual interaction and social media. Drive even deeper differentiation and engagement by adding a dose of "giving back" and philanthropy to the equation—à la the "Life is Good" festival—and then, man, you really have something. A virtuous—truly virtuous—cycle of online/offline/impact and connection. To forge bonds and mobilize like only music and media can do.

Restoring the Value of Art and Enforcing Creator Rights—Unapologetically

We live in a world where many share the belief that content is "free" and of fast-growing piracy of music and media. Yet, most of us don't know that. In fact, most believe that earlier rampant piracy has been significantly curtailed by new legitimate services and business models (like subscription streaming). But, it just ain't so. Cisco forecasts that file sharing in North America will grow a massive 51% from 2014-2019 and analyst firm NetNames, in a study commissioned by NBCUniversal, concludes that virtually all P2P file sharing violates copyright. And, leading consulting firm Bain & Company is reported to have concluded that recorded music sales would be 17 times higher in a piracy-free world.

Piracy robs creators, plain and simple. In the words of Alex Ebert, lead singer of indie band Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros (and a tech innovator himself), "it degrades the craft." The act of creation is their work—it is their livelihood. Circumventing payment for the results of that work (music, movies, television) is like asking someone to build you a house (or even a dollhouse) and then refusing to pay for it. No one can defend that.

Most creators in all forms of media will attest to that (i.e., that the product of creativity is no different) . . . at least privately. So, why is it so hard for artists and other content owners to come out and say that publicly? And, even more, to take the action necessary to proclaim "enough is enough!" and stop the madness (which has, for some, somehow become "right" in some strange twist of fate)? The answer, my friends, is that artists and content owners today are saddled with the history of the past—a history that has led us to today's parallel universe where, for some, the act of stealing from creators has become accepted (and frequently encouraged) behavior and where the "good guys" are the ones frequently depicted with black hats.

Let's go back in time to see how this all happened first in the music business—and to discuss what the creative community can do about it for all forms of media—unapologetically.

The digital age dawned on a mass scale just prior to 2000 and mass piracy of music followed suit. Two enablers of choice in this brave, yet completely unregulated and frequently abused world, included the original Napster and Swedish-born KaZaA (which, in an ironic twist, was born by founders who later started Skype and music streaming service Rdio—for which they expect customers and advertisers to pay). Yes, artists and their representatives felt that something wasn't quite right—that their products were disappearing from the shelves in a form of looting on a mass scale. But things got out of control so fast—and no real tools existed to do anything about it—that little was done to stop illegal downloading of content.

Little could be done. The Internet itself—and the technology enabling that piracy—were still new to everyone. There was no mass education by artists connecting piracy to their livelihoods. Few in the creative community really understood it. And many artists didn't particularly care as a result of a "system" they felt failed to treat them and pay them fairly. So, no one (even the creators themselves) really talked about it. P2P piracy was anonymous. No visible victim. And seemingly everyone did it. After all, it kind of felt good getting great stuff . . . all for free!

Except it wasn't. Not free for the artists and creative community who, like all of us, need to make a living and whose "paychecks" were soon slashed to a fraction. Yes, this happened to major artists who got the most visibility (and the most blowback under the guise of greed when they tried to begin the conversation—perhaps most notoriously, Metallica). But, it happened equally to smaller indie artists and creators—musician "mom and pops"—hitting them right where they live. As an example, since 2000, the number of full-time songwriters in Nashville plummeted 80%. Once artists and the creative community fully grasped the severity of the situation—and the mass global devaluation of their "product" virtually overnight—the music industry struck back with the only tool it knew in those early, frenzied, frightening P2P days. That tool was the good old American lawsuit—a tool that was both horribly imprecise and wielded with an equally horribly imprecise strategic hand.

As a result, that so-called "strategy," which seemed to initially focus most on the least egregious cases of piracy rather than on major pirates, failed. Most importantly, it failed miserably in the court of public opinion, with serious repercussions to artists' and industry brands and images. In a dark form of alchemy, the most egregious wrongdoers proclaimed themselves to be most in the "right" and reveled in stories of 12-year-olds and grandmothers being sued (which purportedly demonstrated pervasive greed across all elements of the music industry). Mass infringers somehow successfully defined a narrative that deflected the real issue and defended their virtual online mass looting of hundreds of millions of creator dollars when virtually no one in their right mind could defend mass theft in the physical world. Imagine a warehouse filled with stolen CDs from your favorite indie artists and then multiply that exponentially (because that was—and remains—the reality in the virtual P2P world). Right? Wrong? You be the judge.

The result? Artists and the creative community were hit where it hurt most—their livelihoods, threatening many from the very act of creation that the most egregious pirates proclaimed they purportedly fostered through their illegal actions. Edward Sharpe's Alex Ebert passionately punctuates this point, underscoring piracy's potential to create a generation of "hobbyist musicians" unable to focus their lives on the arts (and our enjoyment of it). "To master anything, you must be able to devote your whole life to it," he explains, something that is increasingly difficult for creators. That means a generation of lost art—songs, shows, movies that we will never hear or see.

Yet, many of those same creators shied away from protecting their own work, their own intellectual property—fearing losing their fans' support (ultimately their most valuable resource) and frequently lacking motivation in an aging system not equipped for the brave new Internet world. And, in the process, artists and the creative community essentially capitulated to a not-very-brave new world of "well, that's just the way it is."

So, here we are today. What is different today than before? What can (and should) be done now that wasn't done then?

The answer is a three-pronged strategy that is properly defined, clearly articulated, and fairly carried out:

1. Economics. The new monetization realities and consumer Zeitgeist of our digital-first world demand reevaluated artist/label and distributor royalty structures, especially since—as Ebert points out—many consumers are willing to pay only if they believe their money is going directly to the artist.

2. Education. We all know (at least intellectually) that P2P piracy is wrong; artists need to be motivated to openly support one another and be in a position to actively articulate piracy's impact on their lives . . . on their art.

3. Technology. We now, for the first time, have the right set of tools to protect artists, target the most egregious pirates with precision, and seek reasonable restitution efficiently and privately. Forget the 12-year-olds and grandmas—focus on the real bad guys—those with the virtual warehouses of stolen CDs in the sky.

One leader on the technology front is Rightscorp (note: Rightscorp is a client), a company supported by some of the music industry's foremost players (including Peter Paterno and David Lowery), and which identifies content from leading artists like Taylor Swift and Bruno Mars, and counts major industry players like BMG and Warner Bros. as clients. Rightscorp offers artists and content owners a powerful toolkit that helps them solve the dilemma of monetizing their work (and creative livelihood), while also protecting their relationships with their fans. Rightscorp's technology identifies precisely where music, movies, games and any other form of digital content is illegally uploaded or downloaded. Rightscorp is then able to send a series of low-cost offers to resolve the violations that, if continued, ultimately may result in suspension of the abuser's Internet service or in a lawsuit from the copyright owner (but not until many warnings are sent and an ample opportunity is given to stop). In its intent, Rightscorp's technology is not unlike Google's IP protection system called "Content ID" (and others like it). The company's core service follows protocols established by the creative community itself to send—on behalf of artists and other clients—a series of notifications and immediate, discreet settlement options (i.e., no names are made public) so that there are no surprises to recipients and the creative community can take back what's rightfully theirs . . . their livelihoods.

While Rightscorp's technology is capable of identifying all infringers, its clients focus on the most egregious pirates; for example, repeat infringers who rob artists and the creative community at scale (and, therefore, should be considered "fans" only in the parallel universe discussed above). And, this kind of refined technology enables artists and content owners to protect their work/IP, restore massive lost revenue, and protect their names and brands from being tainted for doing what we all know is both understandable and right. Rightscorp—and other tools—put the power back in the hands of creators. In fact, Rightscorp (which represents more than 1.5 million copyrights) has returned more than $750,000 of stolen creativity to date to its partners.

With a significant percentage of all current Internet traffic used to illegally distribute copyrighted content without compensation, artists and content owners are victims still of mass theft valued at multiple billions of dollars just for music. Isn't it time for the creative community to take that back—unapologetically—and help point the way to restoring what Ebert calls "the sanctity of the arts" in the eyes of all of us whose lives profit so much from the creative work of others?

Digital Music Updates

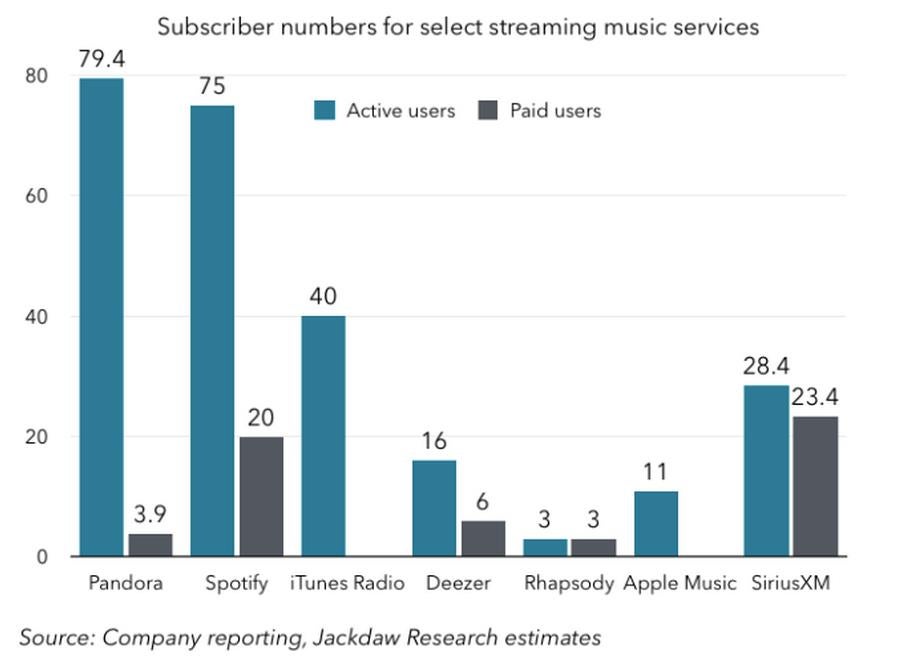

About a month after launching Apple Music, Apple has announced that 11 million users have signed on for the three-month trial. While this number carries Apple a tenth of the way to its goal of 100 million subscribers, the true test will come after the trial period. Apple still has some time to win users over, but so do other players, who are continuing to up their game.

In June, Spotify closed a $526 million funding round at $8.53 billion valuation. Recent reports state that the music streaming service is now considering making certain releases available only to paid subscribers (not unlike Apple Music, which does not offer a free tier). To further differentiate itself from competitors, Pandora announced a major marketing initiative to highlight the Music Genome Project and has recently launched Sponsored Listening, an uninterrupted sponsored listening offering to advertisers.

SiriusXM continues on a growing path, reporting a 46% increase in Q2 subscribers as compared to Q2 of last year, and pushing for closer ties to artists and TV brands, with exclusive concerts by Pitbull and James Taylor. And, second to none when it comes to artist ties, Tidal, which has had a rough couple of months, recently inked a deal with Prince to exclusively distribute the living legend's new album HITNRUN.