Impact of the Pandemic and the End of the Public Health Emergency on Opioid Use Disorder Treatment

Editor’s Note: In a new issue brief, Manatt and the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE) offer providers and policymakers practical information on the current state of play with respect to treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) and put the current environment in the context of lessons learned from the pandemic about how to treat OUD. The analysis, summarized below, is based on a comprehensive review of regulations before, during and after the pandemic, along with closely related changes in federal law and policy regarding OUD that are not directly linked to the PHE, as well as interviews with leading researchers, providers and advocates. Click here to download a free copy of the full issue brief.

COVID-19 was accompanied by serious disruptions in care and treatment for persons with OUD, as well as isolation, loneliness, grief, job loss, and economic and housing instability. All of this undoubtedly contributed to the overdose death rate increasing by 50 percent in the United States during the pandemic. In 2021 alone, over 107,000 lives were lost to overdoses. While drug overdose death rates increased across all racial and ethnic groups, the increases were larger for people of color than for white people, for the young than for the old, and in sparsely populated and economically disadvantaged areas than in urban areas.

Alongside these bleak trends, there are treatments that work. Research demonstrates that methadone and buprenorphine are highly effective medications for treating OUD (MOUD). Unfortunately, these drugs are underutilized. They also come under a strong regulatory framework that, while intended to prevent diversion and protect patient safety, has been criticized for being incongruent with evidence and restricting access to lifesaving treatment.

Recognizing the importance of access to MOUD, many federal COVID-19 pandemic-era flexibilities sought to improve and democratize access, creating the possibility of an even playing field by enacting nationwide telehealth and take-home dose flexibilities for patients who use methadone. These unprecedented flexibilities were coupled with other policy changes seeking to expand access. At the same time, states and providers had autonomy as to how and to what extent they wanted to take advantage of these flexibilities and other policies, which resulted in a patchy and confusing policy landscape and uneven uptake.

With the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) having ended on May 11, 2023, many patients, providers and advocates remain worried about changes to federal flexibilities. There is also confusion as to which policies remain in effect and which expired.

Emerging changes at the federal level suggest four trends for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the post-PHE era:

- A “middle path” for federal limits on access to MOUD. Some pre-pandemic policies will return, making it harder for providers to use telehealth and other strategies to ease access to MOUD, but the rules will not fully reinstate all the limitations of the pre-pandemic era.

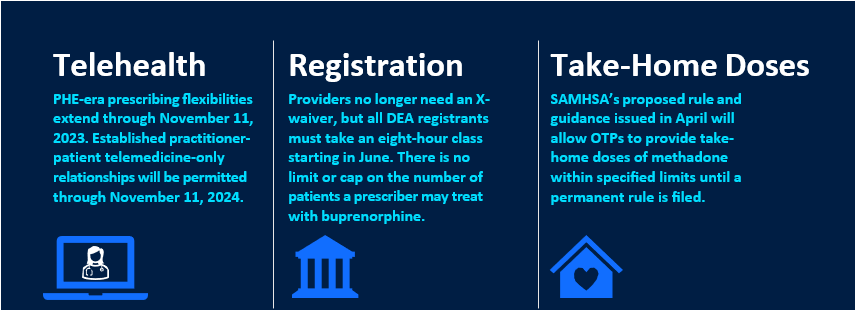

- Temporary preservation of federal flexibilities. The federal government will buy itself time to figure out its permanent position on PHE flexibilities. As demonstrated with recent federal actions, with a few exceptions, most flexibilities remain in place on a temporary basis as the federal government settles on which policies should be in place and works on issuing those policies as permanent regulations.

- Continued state flexibility, contributing to a patchwork of rules. States will continue to have broad flexibility to add their own restrictions on access to MOUD, resulting in variations in what is allowed across the country and compounding providers’ difficulty in understanding the current “state of play.”

- Flexibilities are necessary but not sufficient. As seen during the pandemic, the flexibilities afforded at the federal and state levels are essential, but broader and more systemic changes (e.g., around payment and workforce) will also be needed to support equitable access across the continuum of care.

Federal Regulations

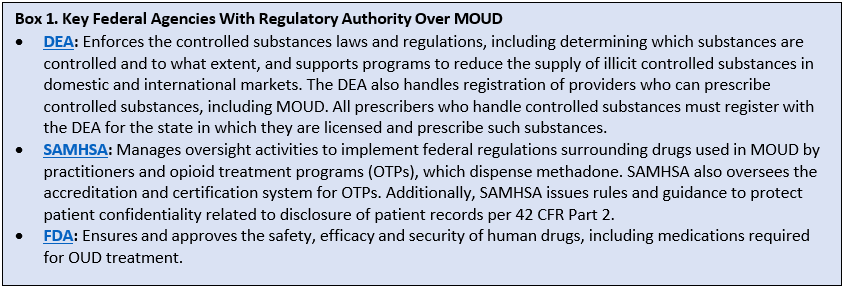

At the federal level, evidence-based treatment for OUD is controlled by multiple agencies but primarily by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). See Box 1 for a description of the role of each of these federal agencies.

The federal regulatory context is detailed and can be confusing. A summary of the current situation as of June 2023 is below.

State Regulations

Intersecting this complex federal policy landscape are state policies. States long have had wide latitude when it comes to regulating care, including but not limited to what is allowed through telehealth; provider licensure, training and education requirements; and additional state-specific rules governing take-home doses for methadone, licensing of OTP facilities and confidentiality protections. The overlapping regulation of SUD treatment by multiple federal agencies and states creates a confusing patchwork of requirements.

During the pandemic, the federal government eased its restrictions, providing temporary flexibilities in telehealth delivery of OUD care, take-home dosing of methadone, education and registration, patient consent, and other elements linked to the PHE. States, however, varied in the extent to which they embraced federal pandemic-era flexibilities—generating an uneven regulatory landscape that is rapidly evolving.

Conclusion

The opportunities created by the pandemic bring with them several calls to action, as noted in FORE’s April 2023 report How Have Covid-Era Flexibilities Affected OUD Treatment? Specifically:

- Democratizing access at the federal level. As underscored by the research, the flexibilities of telehealth and take-home doses—where taken advantage of—helped improve access to care. These flexibilities also afforded providers more discretion to customize treatment protocols based on their patients’ needs and preferences and determine what is clinically most appropriate in the face of shifts in the drug supply.

- Ensuring equitable access at the state and local levels. As noted in FORE’s April 2023 report, “federal regulatory changes are necessary but not sufficient to expand access to treatment.” With the end of the PHE, as federal policies move toward increasingly relaxed regulations, states will maintain their discretion regarding whether and how to support federal regulatory changes.

- Continuing research. As the PHE ends, many policymakers are looking for a “return to normal” as opposed to seeking out the research and acting on lessons learned. A return to normal ignores the important information gleaned during the past three years. We need to develop better measures for quality that hinge on what works, not on what we think we know. Further, as the drug supply continues to change and intensify, it becomes all the more urgent to have actionable and timely data and to continuously research which treatment and harm reduction services are working, as well as information about the most effective ways to increase access.

- Ending stigma. Stigma surrounding people who use drugs is pervasive and creates serious barriers to care. Even with the most data-driven policies in place, there still may be providers reluctant to ease restrictions and expand access, in part because of an implicit bias against drug users in the organization in which they work. During the PHE, this bias—along with risk aversion, financial concerns and the belief that therapeutic bonds require in-person connection—contributed to some providers being less willing to take advantage of the federal flexibilities. As the PHE ends, however, overdose deaths continue to rise. More than ever before, there is an unprecedented understanding of what it means personally to struggle with addiction. Nearly half of Americans have a family member or friend struggling with addiction. With this enhanced shared understanding comes an opportunity to address the overdose epidemic with compassion and empathy—potent antidotes to the stigma that has become so deeply entrenched.

NOTE: For a complete list of sources, click here to access the full issue brief.