DEA Releases Proposed Rules Regarding Telemedicine Prescribing of Controlled Substances

The Big Picture

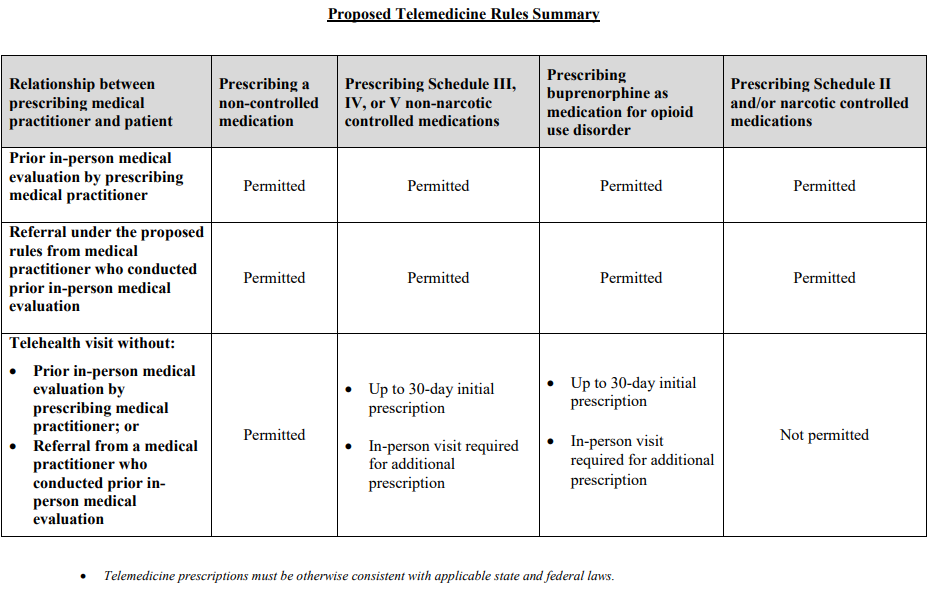

On February 24, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), in consultation with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), issued two proposed rules (here and here) that address the prescribing of controlled substances based solely on a telemedicine encounter. Together, they would make permanent some public health emergency (PHE) flexibilities, but do not go as far as many industry stakeholders were hoping. After the PHE ends on May 11, 2023, individuals will need to have an in-person visit to secure medication via telemedicine except in limited circumstances for select medications. The proposed rules reflect the DEA’s effort to balance access to telemedicine with “guardrails” to protect against overprescribing of controlled substances to people who do not need them. Comments on the proposed rules are due by March 31, and the agency is likely to face significant pressure to go further in offering more flexibility to use telehealth for the prescribing and management of controlled substances.

The proposed rules revert to DEA’s prior requirement that the patient have an in-person evaluation before being prescribed Schedule II medications (which include methadone) and Schedule III-V narcotic medications with limited exceptions. This policy would affect people who are newly prescribed one of these controlled substances after the PHE ends, but also those who began taking such medications during the PHE without an in-person visit. These individuals—many of whom may be stabilized on a medication such as methadone initiated via telehealth only—will have up to 180 days from the publication of the final DEA rules to have an in-person visit. The proposed rules offer greater flexibility to start a 30-day prescription for non-narcotic Schedule III-V medications, as well as for buprenorphine (which is classified as a Schedule III narcotic medication). Note, however, that patients still must have an in-person visit to continue their medications, including individuals stabilized on buprenorphine during the PHE who must secure an in-person visit within 180 days of finalization.

If finalized as written, the proposed rules would not apply to or impact patients who have had an in-person visit with their prescribing or a referring practitioner before being prescribed a controlled substance via telemedicine and would not require a patient to have more than one in-person visit with their prescribing or referring practitioner.

Source: DEA. Proposed Telemedicine Rules Summary.

To many stakeholders’ disappointment, the DEA did not propose the anticipated telemedicine special registration regulation, which would have permitted registered practitioners to prescribe controlled substances based solely on a telemedicine encounter.

The Regulatory Landscape

The Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 (Ryan Haight Act) generally requires practitioners to see a patient in person before prescribing controlled substances, including medications used to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD), unless one of seven statutory exceptions is met. Failure to conduct this in-person medical evaluation can constitute a per se violation of the Controlled Substances Act and result in civil and criminal penalties.

Since March 2020, this requirement was suspended by DEA in light of the HHS-declared PHE, one of the seven statutory exceptions. Authorized practitioners have been able to prescribe buprenorphine and other controlled substances without an in-person visit as a result of DEA flexibilities combined with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) pandemic flexibilities.

DEA is responsible for registration of providers who can prescribe controlled substances, including MOUD. All prescribers who handle controlled substances must register with the DEA for the state in which they are licensed and prescribe such substances.

SAMHSA certifies opioid treatment programs (OTPs), which provide MOUD and are the only facilities authorized to provide methadone.

States also play a role in overseeing controlled substance prescribing and dispensing and often have their own regulatory scheme governing telemedicine prescribing, which can be more restrictive than federal requirements. Thus, a patient’s access to a prescription for a controlled medication based on a telemedicine encounter further depends on the state in which the patient receives services.

The Proposed Rules Expand the Circumstances in Which a Patient May Receive a Controlled Substance Prescription via a Telemedicine Encounter but Significantly Limit the Flexibilities That Existed During the PHE

In issuing the proposed rules, the DEA relies on the existing flexibility under the Ryan Haight Act, which permits dispensing pursuant to the “practice of telemedicine” when it “is being conducted under any other circumstances that the Attorney General and the Secretary have jointly, by regulation, determined to be consistent with effective controls against diversion and otherwise consistent with the public health and safety” as opposed to relying on a “special registration,” which was what many hoped the agency would do.

Under this authority, the DEA proposes that a practitioner may prescribe a controlled substance after only a telemedicine encounter if the medication is a non-narcotic Schedule III, IV, or V controlled substance (or buprenorphine for treatment of OUD), and the prescription is limited to a 30-day period, starting from the date of first prescription. Prescriptions meeting this criterion are called a “telemedicine prescription.” Prescriptions for Schedule II and narcotic Schedule III, IV, and V medications may not be prescribed via a telemedicine-only encounter.

Even for these “telemedicine prescriptions," the patient must have an in-person medical evaluation before they can continue their treatment past the 30-day initiation period. The in-person medical evaluation may be conducted:

- By the prescribing practitioner;

- As part of a two-way exam, where the patient is in the physical presence of another DEA-registered referring provider, and participant participates in an audio-video conference with the prescribing practitioner and the other DEA-registered referring provider; or

- By another DEA-registered referring provider that results in a “qualified telemedicine referral.” The DEA defines a “qualified telemedicine referral” as a referral based on an in-person medical evaluation by another DEA-registered referring provider, who then refers the patient to a second DEA-registered practitioner who prescribes the controlled medications based solely on a telemedicine encounter. The referral must include the diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment that was provided to the patient, and examples in the proposed rule suggest the medical record should also be provided. Both the referring practitioner and the prescribing practitioner must document the referral, among other things (see recordkeeping requirements below), in their medical records.

After the In-Person Encounter, All Subsequent Encounters With the Prescribing Practitioner May Occur via Telemedicine

The DEA clarifies that once any of the three methods of providing an in-person evaluation occurs, the prescribing practitioner may continue to prescribe the controlled medication without additional in-person evaluations so long as there is a legitimate medical purpose.

No Grandfathering of Individuals Who Received Prescriptions via Telemedicine During the PHE

The proposed rules do not include any grandfathering provisions, meaning that all patients who have never had an in-person encounter with their prescribing practitioner must have an in-person exam in order to continue being prescribed medication. For patients who have established a telemedicine relationship during the COVID-19 PHE (now a defined term in the proposed regulation), the patient will have up to 180 days from the date the final rule is published to have an in-person exam (as described above).

Referring Practitioners and Prescribing Practitioners Will Have Increased Recordkeeping Requirements for Telemedicine Prescriptions

The prescribing practitioners must notate on the face of the prescription or within the order, if prescribed electronically, that the prescription is being issued via a telemedicine encounter, in addition to keeping detailed logs of each prescription issued.

Prescribing practitioners must also use all efforts to access the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) system (or the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) internal prescription database) and review the patient’s prescription history for the past year (or available period if less than a year). If the prescribing practitioner cannot gain access to the system or database, the practitioner may only prescribe a seven-day supply of the medication and must document the dates and times that it attempted to gain access.

A prescribing practitioner who issues a prescription based on a telemedicine encounter must maintain a detailed log for each prescription, including, among other things, the practitioner’s address, all efforts to access the PDMP system or VA’s database, and, as applicable, the name and National Provider Identifier of the referring provider and documentation of its communications.

A practitioner who conducts the in-person exam prior to making a referral to the prescribing practitioner is also required to keep detailed logs, including the time and date of the encounter, and the name of any DEA-registered practitioner in the physical presence of the patient.

Our Takeaway

Given the impending end of the PHE, DEA was challenged to balance the policy goal of maintaining access to care given the ongoing opioid crisis and persistent health care access challenges with a desire to protect the public from overprescribing of controlled substances via telemedicine. On the one hand, the proposed rule provides additional flexibilities than existed pre-pandemic on a permanent basis for initiating treatment for opioid use disorder via telemedicine. On the other hand, after the PHE ends, an in-person visit will be required for a patient to sustain treatment long-term and even the flexibility to initiate treatment without an in-person visit applies only to select controlled substances; individuals who need methadone or Adderall will be required to have an in-person visit even to initiate medication. Early responses to the proposed rules indicate that many stakeholders fear the DEA has come down too heavily on the side of preventing overprescribing at the expense of access to care, particularly for people facing life-threatening mental health and substance use disorders.

About Manatt on Health

Manatt on Health provides in-depth insights and analysis focused on the legal, policy and market developments that matter to you, keeping you ahead of the trends shaping our evolving health ecosystem. Available by subscription, Manatt on Health provides a personalized, user-friendly experience that gives you easy access to Manatt Health’s industry- leading thought leadership. Manatt on Health serves a diverse group of industry stakeholders, including five of the top 10 life sciences companies, as well as leading providers, health plans, hospitals, health systems, state governments, and health care trade associations and foundations. For more information, contact Barret Jefferds at bjefferds@manatt.com.