Building a Collaborative Care Model: Lessons from Integrating Behavioral Health into Primary Care

This newsletter has been adapted from findings from a December 2023 report, The Collaborative Care Model in North Carolina: A Roadmap for Statewide Capacity Building to Integrate Physical and Behavioral Health Care.

Context and Introduction

As the national crisis in behavioral and mental health care continues to worsen, providers have tested innovative ways to bring services to children and adults in need. One approach to enhance service delivery is the integration of behavioral and mental health services into the primary care setting. Collaboration between primary care providers and specialized mental health care providers allows services that were historically delivered separately to be delivered in the same setting and ensures a patient’s “whole-person” health needs are met during care delivery.1,2

The Collaborative Care Model (CoCM), a team-based model of care delivery, is a promising integration model with a substantial evidence base. This newsletter summarizes key elements of CoCM and lessons learned from provider implementation in North Carolina.

Overview of the Collaborative Care Model

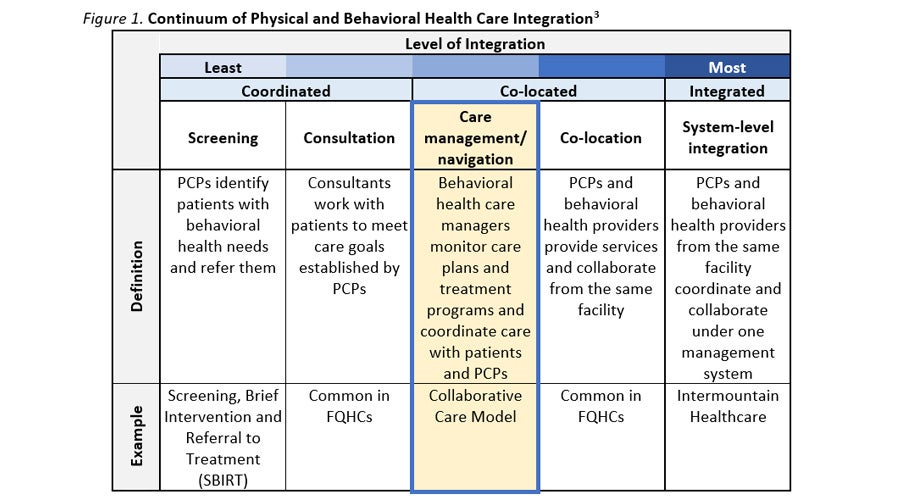

Several models for integrated behavioral and mental health and primary care services exist. Figure 1 lists select integration models ranging in intensity of integration of services, providers and the patient.

Note: PCP refers to primary care providers; FQHCs refers to Federally Qualified Health Centers.

CoCM is an example of co-located services, through which patients can access behavioral and mental health services in their primary care clinic. The Model was developed by the University of Washington in the 1990s and is geared toward patients with mild-to-moderate behavioral health conditions.4,5 The Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) Center at the University of Washington defines five “core principles” of CoCM:6

- Patient-Centered Team Care, in which providers collaborate to engage patients and provide care;

- Population-Based Care, in which the patient population and outcomes are tracked by practices via a registry;

- Measurement-Based Treatment to Target, in which the patient’s treatment plan includes measurable goals and outcomes that treatment is responsive to;

- Evidence-Based Care, in which treatment has a strong foundation of evidence to support it; and

- Accountable Care, in which reimbursement is contingent on the quality of provided care.

The team-based structure of CoCM involves three provider types: the billing practitioner, the behavioral health care manager (BHCM) and the psychiatric consultant.

- The billing practitioner is generally a physician or non-physician primary care provider (PCP) (e.g., family medicine physicians, pediatricians, OB/GYNs, geriatricians) but can be a different type of specialist.7 Billing practitioners use the expertise of the BHCM and psychiatric consultant to treat a patient’s behavioral health problems alongside their physical health concerns.

- The BHCM is a professional (e.g., clinical social worker, nurse) who executes care management activities in alignment with the patient’s treatment plan. The AIMS Center recommends that this role be performed by a full-time, or nearly full-time, staff member.

- The psychiatric consultant is a professional in a support role, generally a psychiatrist, who acts as a resource to the billing practitioner and the BHCM. The psychiatric consultant’s job is to provide virtual consultation, rather than to see the patient.

CoCM is considered to have one of the strongest evidence bases of any integrated behavioral health model, and more than 90 randomized clinical trials have demonstrated its cost-effectiveness and positive impact on patient outcomes across many settings and population groups.8,9 The bottom line for providers is that CoCM can equip them to better handle patients’ mental health needs in a time of increased focus on behavioral health and wellness.

Lessons From Providers Who Have Implemented CoCM

As with any new model, there are several operational changes providers must undertake to adopt CoCM. These include:

- Hiring and training a BHCM;

- Training practice clinical staff – primary care physicians, physician assistants, nurses – on the model;

- Updating clinical and electronic health record (EHR) workflows;

- Implementing a registry to track member engagement, ideally one that integrates with the EHR; and

- Training practice management and billing staff on CoCM codes and billing best practices.

Estimates indicate that 3-month startup costs for new practices adopting CoCM could amount to roughly $30,000.10 Though the high start-up investment required to adopt CoCM could present real barriers to new practices interested in implementing the model, there are solutions to streamline administrative burden and deal with other common challenges that successful practices have learned.

Reacting to the Reimbursement Landscape

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began reimbursing CoCM in Medicare using three time-based Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes – 99492, 99493, and 99494 – and, for rural health clinics and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code G0512 in 2018.11,12 As of 2021, providers are also able to leverage HCPCS code G2214 for shorter amounts of time spent with Medicare patients.13 However, as of 2022, only 19 state Medicaid programs cover CoCM for adults in their FFS programs, and commercial coverage varies by payor and state.14 Though the reimbursement landscape for CoCM has been trending in a positive direction, it can be difficult to navigate the inconsistent treatment of CoCM by insurance providers.

The University of North Carolina Health (UNC) encountered this issue when they began their latest effort to adopt CoCM in 2018.15 To adopt CoCM in the initially misaligned reimbursement landscape of North Carolina, UNC made the decision to limit enrollment at first to Medicaid and Medicare patients in one clinic. Between 2021 and 2022, as the overall reimbursement landscape improved and UNC identified additional funding opportunities, they began to expand to additional clinics. CoCM is now available at seven of UNC’s primary care practices, spanning urban and rural communities.

Partnerships with Third Parties

For smaller practices or those without the resources to invest in the operational changes required to adopt the model to fidelity, administrative burden can be a difficult hurdle to overcome. Providers have found success through partnerships with third-party entities who can take on administrative and operational management and leave practitioners with the actual work of providing care.

One Health – a group of primary care practices in and around Charlotte, NC – had attempted, without luck, to adopt CoCM for several years. They began looking for third-party groups that could support adoption and in 2022 partnered with MindHealthy PC – a provider-owned company focused on helping primary care providers adopt CoCM, whose person-centered mission aligned with One Health’s values. Through the partnership, MindHealthy provides One Health with behavioral health care managers, psychiatric consultants and case management technology for registry management and time-based code tracking. MindHealthy is also now integrated into One Health’s EHR and handles the CoCM registry. As of June 2023, the partnership had embedded CoCM in five One Health practices, with the ultimate goal of using CoCM in all 29 of its practices.

Hiring BHCMs

Adopting CoCM Model requires practices to employ a BHCM. Depending on insurer reimbursement and practice-specific restrictions, the BHCM position can be filled by several types of professionals with behavioral health training, including nurses and clinical social workers.16 However, many practices have still found it difficult to find, train, and cover the costs of full-time BHCMs.

Some practices have addressed this issue by leveraging existing relationships with relevant professionals. For example, UNC employed social workers who were already supporting the Chronic Care Model deployed in the Department of Family Medicine’s practice as CoCM BHCMs. One of these BHCMs operates fully virtually to serve the eastern, more rural part of the state. Similarly, Dayspring Family Medicine in Eden, North Carolina launched the Model within their practice with a former nurse who had been on staff for over 20 years. Dayspring’s BHCM specifically started in her role part-time before shifting to full-time; this slow ramp-up allowed Dayspring to organize and be responsive to practice-specific operational issues they encountered.

The Importance of Local Context

While adoption of CoCM can be streamlined and made easier through innovative solutions by providers themselves, it is important to note that local context can present unique barriers or incentives to deploy the Model. These include:

- CoCM Adoption Initiatives: The high start-up investment required to adopt CoCM is a real concern for providers interested in the model. Some states have developed funding opportunities to defray these costs. For example, North Carolina passed a budget in 2023 with substantial investments in behavioral health, including $5 million earmarked for capacity building for primary care practices across the state to adopt CoCM. Some insurers have also offered funding or other technical assistance to their network providers to adopt the model. Similar initiatives may present opportunities for providers, particularly independent practices, to adopt the model.

- Coverage Alignment: Practices have found it easier to adopt CoCM in states with broad coverage alignment across payors. This includes not only alignment in rates but also in requirements for coverage, such as the types of professionals that can fulfill the BHCM role. Providers may find it less burdensome to adopt CoCM in areas where major payors align on coverage requirements.

- Reimbursement Rates: Insufficient rates for CoCM can present a difficult barrier for providers to overcome. Due to the high start-up cost for CoCM, several North Carolina providers credited reimbursement increases by public payors – including when NC Medicaid began to reimburse CoCM at 120% of Medicare – as making adoption and expansion more financially sustainable.

CoCM is one of the most widely studied and effective integrated care models and is one way to bring whole-person care to patients. Practices considering its adoption should consider their local environment and lessons learned from other practices that have successfully implemented it.

1 “Behavioral Health Integration,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last modified: March 8, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/documents/access-infographic.html.

2 “What is Integrated Behavioral Health?”Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, accessed February 5, 2024, https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/about/integrated-behavioral-health.

3 Adapted from: Celli E. Horstman, Sara Federman, and Reginald D. Williams II, “Integrating Primary Care and Behavioral Health to Address the Behavioral Health Crisis” (explainer), Commonwealth Fund, September 15, 2022, https://doi.org/10.26099/eatz-wb65.

4 “EVIDENCE BASE FOR COCM,” AIMS Center at the University of Washington, accessed February 5, 2024, https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/evidence-base-cocm.

5 Staff News Writer, “Collaborative care model for mental health, addiction treatment,” American Medical Association, December 30, 2020, https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/collaborative-care-model-mental-health-addiction-treatment.

6 See the AIMS Center at the University of Washington, Psychiatry & Behavioral Health Services, Division of Population Health for complete model overview. Accessible at: http://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/principles-collaborative-care.

7 “Behavioral Health Integration Services,” Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, May 2023, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mln909432-behavioral-health-integration-services.pdf.

8 “Improving Behavioral Health Care for Youth Through Collaborative Care Expansion,” Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute, May 2023, https://mmhpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Improving-Behavioral-Health-Care-for-Youth_CoCM-Expansion.pdf.

9 “EVIDENCE BASE FOR COCM.”

10 Estimate provided by North Carolina’s Collaborative Care Model Consortium.

11 “Behavioral Health Integration Services,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, March 2021, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/BehavioralHealthIntegrationPrint-Friendly.pdf.

12 “Care Management Services in Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) Frequently Asked Questions,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 2019, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/FQHCPPS/Downloads/FQHC-RHC-FAQs.pdf.

13 “Behavioral Health Integration Services” (2021).

14 “Medicaid Behavioral Health Services: Collaborative Care Model Services,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed February 5, 2024, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/medicaid-behavioral-health-services-collaborative-care-model-services/.

15 UNC has long-standing efforts to promote integrated care. This paragraph refers to its most recent investment in CoCM.

16 “Behavioral Health Integration Services” (2023).