How States Support Safety Net Hospitals through Innovative Funding Approaches

his is the second edition of a Manatt Health series on safety net hospitals. To read the first issue on how safety net hospitals can benefit from the new Medicaid Access Rule, click here.

Key Takeaways:

Importance of Safety Net Hospitals: Safety net hospitals are crucial for health equity, providing essential services to marginalized communities – including behavioral health and trauma care – despite financial challenges due to low Medicaid reimbursement rates.

Innovative Medicaid Funding: States like Illinois are exploring new Medicaid funding models that focus on supporting safety net hospitals through targeted payments, specifically addressing areas like health equity transformation and maternal health services.

Capital Support Strategies: Safety net hospitals are securing capital support through state grants, philanthropy, and bonds.

Global Budget Models: States like Maryland and Pennsylvania have implemented global budget models that cap healthcare costs, showing promise in improving care quality, though their financial benefits for safety net hospitals are not yet consistent.

Safety net hospitals are critical institutions for advancing health equity in marginalized communities. They provide important services – including behavioral health and trauma services – that would otherwise be unavailable in their neighborhoods. At least 30% of patients receiving care at safety net hospitals are covered by Medicaid or are uninsured.1 However, in many states, Medicaid payment rates do not cover costs, which drives financial distress for these facilities, including insufficient operating support and access to capital.2

Federal and state governments have made policy choices over decades that have led to the current system, where safety net hospitals serve communities with significant healthcare needs yet are severely under-resourced. Some states, however, are experimenting with new financial models to sustain and transform safety net hospitals. This brief explores some of these innovative approaches and describes potential opportunities ahead.

Strategy #1: Target Medicaid supplemental funding streams to safety net hospitals, focusing on state directed payments (SDPs).3

Federal Medicaid rules permit states to make supplemental payments to Medicaid providers, which compensate for low base rates. There are different types of supplemental payments – including disproportionate share hospital payments, upper payment limit payments, graduate medical education payments (GME), and SDPs – each governed by different rules on provider eligibility and payment distribution. SDPs are the largest type of supplemental payment, reaching almost $80 billion in 2023. In its April 2024 final rule, CMS codified the average commercial rate as the SDP limit, formalizing a limit it has used since 2017.

Several states—most notably Illinois—have developed creative, tiered Medicaid funding streams to support safety net hospitals. Illinois structures its entire Medicaid supplemental funding program around these hospitals’ needs, using multiple payment levers to invest in operating support, transformation, and workforce needs. The state provides a per-diem payment increase in Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) and managed care, along with an SDP specifically targeted to safety net hospitals. Additionally, Illinois reimburses these hospitals for addressing specific priority areas, including transformation projects to advance health equity, enhanced maternal health service reimbursements, and GME payments for the pediatric healthcare workforce.

See Appendix Exhibit 1 for additional examples in other states.

Looking Ahead. States are likely to further leverage SDPs for safety net hospitals, especially in light of flexibilities under the 2024 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule that provide states with new opportunities to promote parity between Medicaid and commercial rates. For more on new flexibilities under the managed care final rule, see the first brief in Manatt’s safety net series.

Strategy #2: Secure capital support through state grants, philanthropy, and bonds.

Health systems generally fund their capital needs through operating profits, credit access, and philanthropy. However, safety net hospitals, with operating models where reimbursement does not cover costs, face near-constant deficits and limited credit market access. Some states and providers are experimenting with new models, including grants, philanthropy, and bonds.

State capital grant funding. Example: New York State. In 2024, New York established its fourth and fifth rounds of transformation grants, including $950 million for (1) technology, telehealth, cybersecurity projects, (2) capital projects to redesign and strengthen healthcare services, and (3) alternative nursing home models. These grants support safety net hospitals and a wider group of providers. To qualify, healthcare providers must respond to the state’s request for application and demonstrate how the project benefits Medicaid, Medicare, and uninsured individuals, contributes to improved quality or access to care, and improves financial sustainability.

Bond Issuance. On the national level, hospitals may reduce their cost of capital via Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance, allowing qualified hospitals to issue bonds ensured by the federal government.4 Unfortunately, this pathway is not available to many safety net hospitals, given the eligibility criteria. Some safety net hospitals have partnered with their state, city, or county governments to finance critical capital projects. Public safety net hospitals often rely on their county’s or city’s taxing authority, while private safety net hospitals may access tax-exempt revenue bonds with government support.

Example: Public safety net hospital. Harris Health System, Texas’ largest safety net hospital system, is using a $2.5 billion bond approved by Harris County residents in 2023 to renovate its hospitals and clinics. The funding will support construction of a new Level I-capable trauma facility, new community-based clinics in high-need areas and other necessary facility improvements over the next ten years. The bond will be funded by residential property taxes5. In addition to the bond, the funding for the construction will come from philanthropic support ($100M) and operating savings ($300M)6.

Examples: Private safety net hospitals. In 2019, Richmond University Medical Center, a private community safety net hospital in Staten Island, New York, accessed a $132M tax-exempt revenue bond to finance its capital needs. The bond is backed by RUMC’s revenues and mortgage liens; it was issued by Build NYC Resource Corporation7 and purchased by a social impact municipal finance company, Preston Hollow8.

New York’s Secured Hospital Program is another, larger example of government-supported, private safety net hospital bonds. The Program operated between 1985 and 2015, enabling critical capital funding for 11 severely distressed safety net hospitals whose facilities required urgent renovations and were no longer-code-compliant. In the event that hospitals could not repay the bonds, the state guaranteed the debt after several layers of security (i.e., capital reserve fund, special debt service fund and other funds9).

Philanthropy. In 2011, San Francisco General Hospital Foundation launched a Capital Campaign raising more than $140M to equip San Francisco General Hospital’s new acute care and trauma facilities with critical medical equipment10. Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Dr. Priscilla Chan donated $75M, which is believed to be the largest private gift from an individual donor to a public hospital in the country.11 The hospital remains essential to community caring for 20% of all San Francisco residents, with over 70% of patients who are underinsured or uninsured.

Looking Ahead. For safety net hospitals, pathways to capital support remain fragmented, and large capital needs remain. Nevertheless, grants, bond issuances and philanthropy are viable strategies that are succeeding in some states.

Strategy 3: Consider global budget models to support financial stability and transformation.

Maryland12 and Pennsylvania13 have partnered with CMS to implement federal-state demonstration models that aim to limit growth in total cost of care. Both models include a hospital global budget, in which participating hospitals receive a fixed payment from all payors to care for their patient populations. The models have demonstrated benefits in care quality and efficiency, reducing health disparities, and strengthening care coordination, but thus far they lack consistent financial improvement for safety net hospitals.

Looking Ahead: CMS recently introduced the States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model, with Maryland, Vermont, Connecticut and Hawaii as the first state participants14. The goals of the AHEAD model are to improve overall population health, reduce health disparities, and curb health care cost growth, using hospital global budgets as a key lever.

Under AHEAD, participating hospitals in selected states will receive hospital global budgets to provide inpatient and outpatient services to Medicare FFS enrollees. The Medicare FFS methodology will serve as a starting point for other payers’ methodologies, including Medicaid, though states will have opportunities to adjust the Medicaid methodology.15 In Medicare, a hospital’s baseline will be based on its historical inpatient and outpatient revenue and adjusted for factors that influence hospital care costs (e.g., inflation, demographic changes).

The stable revenue afforded by the global budget of the AHEAD model should allow for better predictability of cash flow for safety net hospitals. However, if baseline payments are below costs, locking in inadequate payments provides predictability but not stability. There are related health equity implications, too, since safety net hospitals disproportionately serve people of color who may be under-utilizers of services and thus may not be reflected in baseline calculations.16 If the baseline reimbursement of the AHEAD model is not adequate, safety net hospitals will continue to struggle financially.

The Path Forward: Developing Strategies to Navigate Safety Net Funding Challenges

Safety net hospital financing is a failure of public policy, but the tools are available to fix it. States, safety net hospitals and consumer advocates can build upon new federal flexibilities and examples in other states to build sustainable funding models. As a starting point, stakeholders can consider he following questions:

Does the state’s Medicaid program target supplemental funding streams—including state directed payment—to safety net hospitals? If so, can states take advantage of new federal Medicaid flexibilities to increase payment levels?

Does the state offer operating or capital grant programs for safety net hospitals? If not, how can stakeholders advocate for developing a program?

Can states or local municipalities leverage public financing, including bond issuances, to finance capital funding needs?

How can safety net hospitals build effective philanthropic campaigns?

Answering these questions will help states and safety net hospitals begin to develop new sustainable funding pathways based on models that are already working in other states.

Appendix

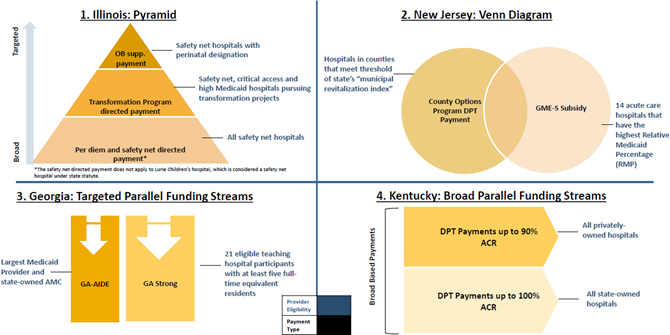

Exhibit 1: Leader States Use Different Approaches to Layering Funding Streams for Safety Net Hospitals

Source: Manatt Analyses

1 How States Can Ensure Safety Net Hospitals Benefit from the New Medicaid Access Rule, July 2024. Available at: https://www.manatt.com/insights/newsletters/health-highlights/how-states-can-ensure-safety-net-hospitals-benefit 2 Deborah Bachrach, Laura Braslow, and Anne Karl, “Toward a High-Performance Health Care System for Vulnerable Populations: Funding for Safety-Net Hospitals Prepared for the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High-Performance Health System.” The Commonwealth Fund. March 2012. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2012/mar/toward-high-performance-health-care-system-vulnerable 3 In addition to state directed payments, 1115 waivers have been increasingly used by CMS and states to make changes to the healthcare delivery system. During the Biden administration, 1115 waivers have focused on reducing health disparities, addressing social determinants of health, and expanding Medicaid eligibility. The direction of 1115 waivers is highly dependent on federal administration and is not the focus of this brief. 4 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “About the FHA’s Section 242 Office of Hospital Facilities”. Available at: https://www.hud.gov/federal_housing_administration/healthcare_facilities/section_242/About_242 5 “Harris Health: $2.5B Bond for Harris Health Infrastructure. Letter from President & CEO.” 2023. Available at: https://www.harrishealth.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/bond/Harris_Health-bond_book-08-08%20-%20digital%20version.pdf 6 “ Harris Health breaks ground on new hospital project on LBJ campus,” May 10, 2024. Available at: https://www.uth.edu/news/story/harris-health-breaks-ground-on-new-hospital-project-on-lbj-campus 7 Build NYC Resource Corporation is a not-for-profit local development corporation created at the direction of New York City Mayor and authorized to promote community and economic development, including tax-exempt and taxable financing for eligible projects. The corporation has no taxing power; the bonds it issues are not backed by credit or taxing power of city or state. “Limited Offering Memorandum,” December 19, 2018. Available at: https://edc.nyc/sites/default/files/2019-10/buildnyc-official-statement-richmond-medical-center.pdf 8 Businesswire, “Preston Hollow Capital Completes Richmond University Medical Center Financing.” January 28, 2019. Available at: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190128005059/en/Preston-Hollow-Capital-Completes-Richmond-University-Medical-Center-Financing 9 Dormitory Authority State of New York, “Secured Hospital Revenue Refunding Bonds (Wyckoff Heights Medical Center), Series 2015”. 2014. Available at: https://www.dasny.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Secured_Hospital_Revenue_Refunding_Bonds_Wyckoff_Heights_Medical_Center_Series_2015_dated_1_22_15.pdf and Fitch Rating Action Commentary available at: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/us-public-finance/fitch-rates-dasny-60mm-secured-hospital-bonds-aa-outlook-stable-30-12-2014 10 Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, “Our History.” Available at: https://www.zuckerbergsanfranciscogeneral.org/about-us/our-history/ 11 San Francisco General Hospital Foundation, “The Heart of Our City.” Available at: https://sfghf.org/news/the-heart-of-our-city/ 12 Maryland Total Cost of Care Model (TCOC) builds on its predecessor - Maryland All-Payer Model (2014-2018), which was focused entirely on the hospital setting. Maryland TCOC incorporates nonhospital healthcare providers. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Maryland Total Cost of Care Model.” Available at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/md-tccm 13 The Pennsylvania hospital global budget model is limited to rural hospitals in the state. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “ Pennsylvania Rural Health Model.” Available at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/pa-rural-health-model 14 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model.” Available at: https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/ahead 15 Participation of commercial payors is voluntary, though states are required to contract with at least one commercial payor. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Model: Hospital Global Budget Fact Sheet.” Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ahead-hgb-fs.pdf 16 “ CMS' AHEAD Model Medicaid Hospital Global Budget Design and Implications,” July 1, 2024. Available at: https://manattonhealth.manatt.com/Health-Insights/Manatt/Newsletters/pages/Manatt%20Viewer.aspx?SpoId=961#:~:text=who%20may%20be-,under,-%2Dutilizers%20of%20services