Editor’s Note: In a recent "State Spotlight" for The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, reprinted below, Manatt Health discusses the investments and efforts that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is making to promote health equity in and through the state’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) program, otherwise known as MassHealth.

Introduction

While the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the structural racism experienced by people of color, racial and ethnic inequities in healthcare resulting from structural racism have long been a reality in the United States. Evidence of the profound impact of such inequities nationally is well-documented, with Black, Latino/a, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Medicaid enrollees experiencing barriers to care and worse health outcomes as compared to White enrollees. Black and AI/AN people are also more likely than White people to die prematurely from conditions that are treatable. In Massachusetts, Black and Latino/a people are less likely to report “Excellent or Very Good” health, and report higher rates of diabetes and asthma than White people.

Medicaid provides essential healthcare services to more than 94 million individuals nationally—about 60% of whom identify as Black, Asian, AI/AN, Hispanic/Latino, or Pacific Islander. Given the large role that Medicaid plays in coverage and care nationally and for AI/AN, Black, Latino/a and other people of color, a growing number of states are using Medicaid as a key lever to promote health equity in their healthcare systems writ large. This state spotlight highlights the investments and efforts that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is making to promote health equity in and through the state’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), otherwise known as MassHealth.

MassHealth’s Approach to Making Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program More Equitable

As of June 2023, MassHealth covered over 2.4 million people, approximately a third of all Massachusetts residents, including many low-income children and families, individuals experiencing homelessness, and adults and children with severe and/or chronic physical and behavioral health needs. MassHealth enrollees are also disproportionately Black and Latino/a people who face disproportionate barriers in accessing coverage and care due to historic and current policies and social and structural factors. For example, Black and Latino/a people in Massachusetts often struggle to obtain timely access to a doctor or clinic and are more frequently told the provider does not accept their insurance.

MassHealth is taking bold steps to address these inequities and implement sustainable and transformative health equity interventions by leveraging a variety of polices, federal authorities, and state and federal funding sources. These efforts are grounded in MassHealth’s commitment to mitigating health disparities and eliminating health inequities, and are designed to increase access to affordable, high-quality care and improve clinical health outcomes. Below we highlight five cross-cutting areas of focus in MassHealth’s multi-pronged health equity strategy: community engagement; social drivers of health [referred to in this brief and by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as health-related social needs]; continuous enrollment; perinatal health; and provider and health plan incentives.

Engaging the Community

MassHealth has prioritized community engagement in developing its health equity goals, aiming to reflect the priorities of its members in policies and processes and expand opportunities for members to inform its efforts to mitigate inequities they experience when engaging with MassHealth and the healthcare system. Equity-focused member engagement efforts will build on existing structures that include MassHealth members and their families in committees, councils, workgroups, and policy-focused ad hoc discussion groups. For example, the state established the One Care Implementation Council in 2013 to focus on the complex needs of people with disabilities (under age 64 at the time of enrollment) who are enrolled in both MassHealth and Medicare. The Council’s charter requires that at least 51% of participants be enrollees or family members of enrollees. Additionally, each of the accountable care organizations (ACOs) and managed care organizations (MCOs) contracting with MassHealth maintains connections with a patient and family advisory council (or a similar consumer committee). In 2021, MassHealth published a request for information (RFI) on its consumer engagement efforts to assess barriers to participation, format and content preferences, and opportunities to deepen and expand this work. Based on the RFI responses, MassHealth is considering potential new initiatives, including standing-up a member engagement committee overseen directly by MassHealth and/or leveraging technical assistance from external community-based partners. Partnering with community-based organizations was one recommendation that emerged from the RFI as a means to further strengthen relationships with and engagement of members and their communities. Such partnerships can be especially effective when trying to engage communities who experience health inequities.

Addressing Health-Related Social Needs

Social and economic structural racism is a factor that influences health-related social needs and results in health inequities. These health-related social needs, such as food insecurity and housing instability (i.e., homelessness and risk of homelessness), are associated with worse health outcomes and higher healthcare costs. In Massachusetts, as in much of the nation, Black and Latino/a residents experience greater health-related social needs than White and Asian residents, including higher levels of food insecurity and housing instability. While Medicaid cannot fully solve social and economic inequality, the healthcare system has an important role in identifying and addressing (via interventions and connection to other services) health-related social needs as part of whole person care.

When MassHealth launched its ACO program in 2018, it was the most significant restructuring of MassHealth’s managed care program since the early 1990s. The ACO program introduced a payment model that required ACOs to manage their healthcare costs and the health outcomes of their members, as opposed to basing payment on the number of services provided. This new payment model created an incentive for ACOs to address upstream factors that influence health outcomes (i.e., health-related social needs). MassHealth incorporated key health-related social needs variables, such as unstable housing and neighborhood stress scores, into its risk adjustment of the rates used to calculate ACO total cost of care budgets. From the beginning of the ACO program, ACOs were contractually required to screen members for health-related social needs and provide navigation supports to connect members with services to address those needs. MassHealth also developed a new quality measure dedicated to tracking each ACO’s health- related social needs screening and introduced financial accountability for screening performance through inclusion of the measure in the ACO quality measure slate used to determine the number of shared savings/losses earned by ACOs.

The next pivotal step that MassHealth took to address health-related social needs was through the implementation of its Flexible Services Program in 2020, funded through the state’s section 1115 Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program. Through this pilot initiative, MassHealth’s ACOs are testing evidence-based initiatives through which contracted Social Services Organizations (SSOs) address Medicaid enrollees’ health-related social needs by providing tenancy supports (e.g., housing deposits, move-in costs) and nutrition supports (e.g., medically tailored meals, food boxes). Eligibility is conditioned on an individual being enrolled in a MassHealth ACO, meeting at least one health needs-based criteria, and meeting at least one risk factor outlined in the Flexible Services Guidance Document. ACOs must perform semi-annual analyses stratifying members receiving Flexible Services using available race and ethnicity data to identify and address inequities in access or outcomes relative to similar members who did not receive Flexible Services. They are encouraged to conduct similar analyses based on other available demographic data (e.g., language, sexual orientation, and gender identity). To help build SSO capacity in partnering with MassHealth’s ACOs to deliver Flexible Services, MassHealth and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health collaborated to provide approximately $4 million in waiver funding for SSOs. While still in the early phases of program implementation, initial results from the Flexible Services Program are promising. In the first three years of the Flexible Services Program (2020 to 2022), ACOs launched 85 Flexible Services Programs with 39 different SSOs serving 20,580 unique members. One ACO, Community Care Cooperative, observed a $11,309 reduction in annualized total cost of care per member who received nutrition supports compared to a $345 reduction in the comparison group.

In September 2022, CMS approved an extension of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ section 1115 demonstration—giving the state continued authority for the provision of the Flexible Services Program under a new federal health-related social needs framework.1 Under this new framework, Massachusetts may continue to offer services addressing health-related social needs to a broad range of populations that meet health-related criteria (e.g., behavioral health needs, complex physical health needs, frequent emergency department utilization) and have specified risk factors (e.g., at risk for nutritional deficiency). Additionally, the Commonwealth received new authority to provide additional meal support to households of children identified as high risk or high-risk pregnant individuals; and Medicaid eligibility for members experiencing a high-risk pregnancy has expanded from up to two months postpartum to up to 12 months postpartum. MassHealth will integrate the Flexible Services Program into the ACO managed care structure (e.g., complying with rate setting and network adequacy requirements) by 2025.

To recognize and address the unique and often intensive need for support among justice-involved populations and people who are chronically homeless or at risk of eviction, the waiver also expands the existing Community Supports Program (CSP), which is a behavioral health benefit in the MassHealth managed care program that provides high-touch care management and social supports to members. This CSP program offers diversionary services that provide interventions and stabilization to members with mental health needs or substance use disorders who are at high risk for inpatient admission due to the severity of their conditions. As a consequence of systemic racism both nationally and in Massachusetts, individuals from communities of color are overrepresented in the justice system and more likely to experience homelessness. CSP works to support and maintain individuals in the community and prevent them from requiring acute inpatient hospitalization, or to stabilize members after discharge. A specialized form of CSP called CSP for Chronically Homeless Individuals provides housing search and placement supports, transitional assistance, and tenancy sustaining supports for members who experience chronic homelessness. The waiver expands the CSP program to include the fee-for-service population and authorizes three specialized CSPs that provide services to specific members with behavioral health needs: (1) people experiencing chronic homelessness and other homeless individuals who are frequent users of MassHealth acute services, (2) members who are facing eviction as a result of behavior or disability, and (3) individuals with justice involvement.

Also see a SHVS issue brief that reviews recently approved renewals and amendments to several longstanding section 1115 demonstrations—including Massachusetts’—and new guidance from CMS on states’ ability to address health-related social needs through the use of “in lieu of services” in Medicaid managed care.

Implementing Continuous Enrollment

In an effort to promote health equity by ensuring continuity of coverage and care for low-income residents, especially at the end of the federal Medicaid continuous coverage guarantee, MassHealth is instituting new continuous enrollment polices for key groups of enrollees through the state’s section 1115 demonstration. All Medicaid members, particularly individuals who experience homelessness or housing insecurity, churn on and off of coverage at a relatively high rate, including for procedural reasons (e.g., not receiving or responding to requests for information from MassHealth regarding their continued eligibility). For these populations, disproportionately comprised of people of color, maintaining stable coverage is essential to managing chronic physical and behavioral health needs and accessing critical clinical and social supports during a transition back to a community setting. MassHealth will provide 12 months of continuous enrollment for individuals upon release from correctional settings and two years for individuals who are experiencing homelessness. To qualify for two years of continuous enrollment, individuals will need to have experienced at least six months of homelessness, confirmed by the Statewide Homeless Management Information System Data Warehouse or the Department of Housing and Community Development Emergency Assistance Shelter System. The state plans to utilize a manual process to determine eligibility, and, over time, will implement systems changes to enable automatic determinations and incorporate homeless and correctional agency data. Developing strong relationships and an infrastructure to facilitate data exchange between MassHealth and the state’s corrections and housing agencies has been and will remain essential to the planning and implementation process. Further, budget analyses suggest the state’s new continuous enrollment policies are expected to have a significant return on investment as a result of reduced rates of churn and increased access to stable coverage and care for these populations, who face disproportionate risk of illness, injury, and death.2

Prioritizing Perinatal Health

Because of stark racial and ethnic inequities in perinatal outcomes resulting from systemic racism, MassHealth has deployed a robust perinatal health strategy through which the state has extended postpartum coverage, provided enhanced services for birthing individuals, and targeted racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy and birth-related healthcare access and outcomes through quality improvement initiatives. In Massachusetts, Black and Latino/a birthing people are less likely to report receiving adequate prenatal care than White and Asian people. Infant mortality rates in Massachusetts for Black and Latino/a people (6.6 and 5.1 deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively) are substantially higher than rates among White and Asian people (2.6 and 2.9 deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively). Effective April 2022, the state guaranteed 12 months of continuous postpartum coverage in MassHealth, including for lawfully residing birthing individuals, by taking up the state plan option, recently made permanent under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022. To further support low-income residents who are immigrants, the Massachusetts legislature appropriated state dollars to ensure individuals with incomes up to 200% of the federal poverty level, regardless of immigration status, can access 12-months of commensurate postpartum coverage in MassHealth. MassHealth is further seeking to improve outcomes and address racial inequities among pregnant and birthing members and their babies by beginning the process to reimburse doula services and issuing guidance to increase access to Freestanding Birthing Centers.

Additionally, in conjunction with MassHealth’s reprocured ACO program process, the state has established new contractual requirements related to the provision of enhanced care coordination for high-risk perinatal enrollees (e.g., enrollees with a history of complex or severe behavioral or physical health diagnosis, adverse perinatal or neonatal outcomes in previous pregnancies, social risk factors, etc.) throughout pregnancy and up to 12 months postpartum.

Further, MassHealth measures and incentivizes high performance on perinatal quality measures to promote a safe and equitable maternal health environment for pregnant, birthing, and postpartum people. For example, the 2022 MassHealth Comprehensive Quality Strategy prioritizes prenatal and postpartum care; and the new Hospital Quality and Equity Initiative, described below, includes a priority area on perinatal health. Taken together, these policies reflect MassHealth’s sustained long-term investment in and commitment to improving perinatal health at the state level and addressing the identified inequities impacting the maternal and infant health lifecycle.

Incentivizing Providers and Health Plans to Improve Equity

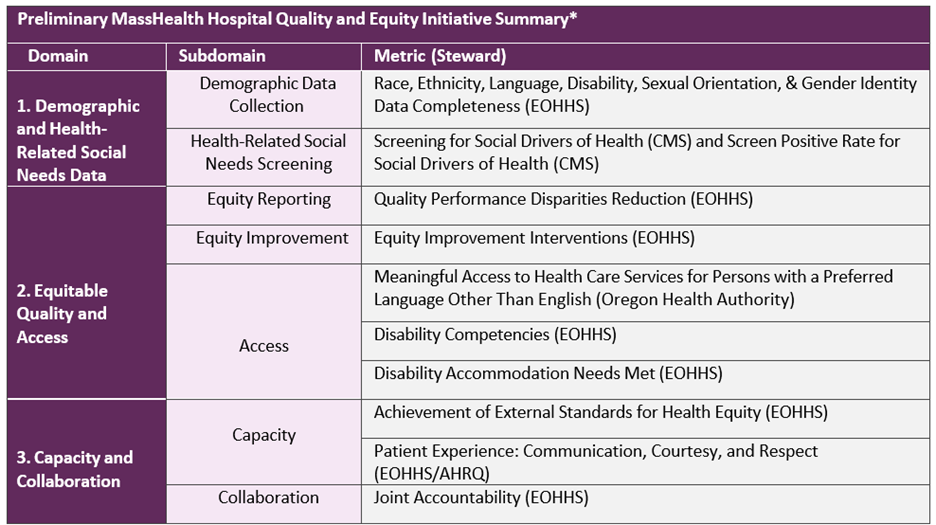

As part of its recent section 1115 demonstration extension, MassHealth aims to improve quality of care and advance health equity. To that end, MassHealth received CMS approval to establish the Hospital Quality and Equity Initiative that provides almost $500 million annually for a hospital equity incentive program [with separate incentive pools for private acute care hospitals ($400 million) and the Cambridge Health Alliance, a non-state-owned public hospital ($90 million)]. MassHealth has proposed to CMS holding hospitals accountable to a set of metrics that fall under priority health equity performance incentive domains, including: (1) improving demographic and health-related social needs data, (2) promoting equitable access and quality, and (3) strengthening capacity and collaboration. Participating hospitals will be able to earn a performance-based incentive payment for meeting data collection requirements; reducing disparities in quality and access, including for members with disabilities and with a preferred language other than English; and for achieving high standards for delivery of equitable care, enhancing cultural competency, and building cross-system and cross-sectoral partnerships around equity.

Under separate authority, MassHealth will hold ACOS, MCOs, and MassHealth’s behavioral health managed care plan (the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, or MBHP) accountable for advancing equity in a manner aligned with hospitals. In 2023, this will make up to approximately $139 million in additional, incentive-based revenue available to ACOs and MCOs based on progress toward equity.

The equity incentive programs for hospitals and ACOs, MCOs, and MBHP will complement existing quality measurement incentive programs in both settings, making equity a pillar of value-based care alongside quality and cost. While performance targets for equity are ambitious, they will hold the state, its providers, and other stakeholders accountable for and ultimately move the needle on achieving health equity.

*Pending CMS approval.

*Pending CMS approval.

Conclusion

With the highest coverage rate in the nation, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has made great strides in ensuring access to healthcare for low-income residents and is now paving the way to reduce racial and ethnic disparities experienced by Medicaid and CHIP enrollees. While considerably more time and work are needed to fully realize the impact of the state’s health equity initiatives, Massachusetts has set itself up for success through its commitment to engage with the community and individuals being served by the MassHealth program and its policies, meaningful collaboration with key partners and stakeholders more broadly, and continued investment.

For other states looking to leverage available federal and state funding to address health inequities, Massachusetts can serve as an example. CMS has signaled clear intent to encourage states to propose waivers that expand coverage, reduce health disparities, and address health-related social needs. Other states, such as Oregon, Arizona, Arkansas, and California are leveraging similar waiver frameworks and state policies to expand Medicaid coverage and services and reduce health disparities. While substantial work is still needed to create an equitable healthcare system, the Biden administration, Massachusetts, and other states are charting an important path forward.

Also see the state spotlight reviewing California’s approach to expanding health coverage to all lower-income residents, regardless of immigration status, in an effort to help the state’s 3.2 million remaining uninsured, of which 65% are undocumented people.

1 At the height of the opioid crisis, the opioid overdose death rate in Massachusetts was 120 times higher for people recently released from incarceration as compared to the general adult population.

2 CMS also utilized a similar health-related social needs framework in the approval and funding of housing and nutrition services and infrastructure investments in the recently approved Oregon 1115 demonstration waiver renewal.