Balancing Gene Therapy’s Promise and Price

- Balancing Gene Therapy’s Promise and Price

- The OIG’s Medicare Agenda for 2017

- OCR Issues New FAQs on the ACA’s Non-Discrimination Provision

- New Manatt Webinar, “Election 2016: Strategic Implications for Healthcare”

- Decisions Regarding Hospice Care for Isolated Patients

- Now You Have a Second Chance to Benefit From “Connecting Medicaid Beneficiaries to Social Supports: The Critical Role of MCOs”

- OIG Issues Final Rules Establishing New Anti-Kickback Statute Safe Harbors and Civil Monetary Penalties Law Exceptions

- Where Are Subsidy-Eligible Enrollees Most Vulnerable to Losing Coverage?

- Antitrust Corner: Telehealth for Healthy Competition

- California’s $20 Billion Problem: The Staggering Cost of Obamacare Repeal Threatens Health Coverage for Over Four Million Californians

- California Court Expands Roadmap for “Reasonable Value” of Providers’ Services

Balancing Gene Therapy’s Promise and Price

By Jon Glaudemans, Managing Director, Manatt Health | Cindy Mann, Partner, Manatt Health | Sandy Robinson, Partner, Manatt Health

Editor’s Note: Exciting advances in science have led to developing treatment breakthroughs, such as gene scripting therapies, that could represent the first potential cures for rare diseases and other life-threatening conditions. Gene therapies offer dramatic promise—but also come with high costs. When viewing gene therapies and other expensive treatment options against the backdrop of an evolving healthcare landscape, several reimbursement challenges emerge. In a new webinar, summarized below, Manatt Health examines the key issues that life sciences companies should consider when developing their reimbursement strategies for high-cost therapies as both public and private payers struggle with balancing budgets against increasing demands. Click here to view the webinar free, on demand—and here to download a free copy of the presentation.

__________________________________________________

What Is Gene Therapy?

Gene therapy is the therapeutic delivery of polymers into a patient’s cells for the purpose of treating a disease. Polymers interfere with gene expression or correct mutations.

There are a number of gene editing technologies. The easiest way to describe gene editing is as a cut-and-paste function in the human genome. Gene editing technologies essentially cut out and replace the defective portion of a gene. There are then a number of ways in which the corrected gene segment can be reintroduced to the body’s system through both viral and non-viral mechanisms.

Two Types of Genes

It’s important to remember that there are two types of genes. Germline genes are responsible for the replication of the body’s genetic material and, if modified, would result in a sustained and reproducible change from generation to generation. Various ethical agreements and strictures have taken editing germline genes off the table.

Somatic genes are the genes that belong to individuals and are not used for reproduction or generational transfer of genetic information. Those are the type of genes used in gene editing therapies.

Gene Editing Technologies and Their Uses

There are a number of gene editing technologies. The latest innovations are Clustered Regularly Interspaced, Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) nucleases and Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) nucleases, both of which are easier to use and less costly than earlier technologies.

Some earlier generations, however, may well be as helpful or more helpful, depending on the disease state. For example, in 2014 the University of Pennsylvania used Zinc-Finger Nucleases on a subpopulation of HIV patients with promising results.

Most recently, the CRISPR-Cas9 technology has captured the popular imagination. In late October, the first CRISPR gene editing technology was tested in China. These are emerging technologies, and they’ll begin to inform coverage and reimbursement as they reach a greater degree of maturity.

As one would expect, first-generation gene therapy products most often address rare genetic diseases that tend to be monogenetic or caused by a single genetic defect. For example, in an ideal world, if a patient has sickle cell anemia and we know exactly why and where that gene is defective, we should be able to edit and correct that defect.

Delivery System Implications

Gene therapy is more complicated than anything we’ve seen to date. It requires the highly choreographed coordination of laboratory, pharmacology, pharmaceutical, inpatient, outpatient and community-based resources. Gene therapies implicate multiple settings of care, payers and payment models, requiring new approaches to reimbursement. The result is considerable complexity and uncertainty for innovators. The need to address gene therapy’s complexities is leading to creative partnership and collaboration opportunities between and among innovative life sciences companies, delivery systems, payers and academic medical centers.

We need to begin thinking about the challenges around tapping into different areas of expertise across different geographies and the implications for payment models. Many of these therapies are best performed in centers of excellence. If a Medicaid-eligible gene therapy patient in North Dakota needs to go to Pennsylvania for some component of treatment, how would payment be handled?

Pricing Challenges

Gene therapies face the challenge of pricing to value, given their curative potential but high cost. Few of the diseases for which gene therapies are used are curable, many are life limiting—and all are expensive to treat. Comparing a high-cost curative therapy to a lower-cost ameliorative therapy starts to raise some interesting financial questions—and to shape the conversation around reimbursement.

Adding to the complexity is the proliferation of governmental and nongovernmental value- assessment organizations—some of which have very short timelines relative to return on investment and many of which impose budget constraints. We still aren’t certain how value-assessment organizations will view very expensive but curative therapies.

Industry Trends

According to the Journal of Gene Medicine, as of August 2016, there were about 2,400 clinical trials being run related to gene therapy. About 1,500 or 43% are focused on oncology, about 250 in the monogenetic field, 180 in infectious diseases and 180 in the cardiovascular category. While oncology is attracting much of the trial work, monogenetics is the low-hanging fruit for gene therapy technologies.

Other Issues Shaping the Gene Therapy Market

There are a number of legal and regulatory issues in play that will shape the gene therapy market, including the patent challenges for the CRISPR-Cas9 technology; the potential ethical questions; and the 21st Century Cures Act, which reforms the standards and appropriations for biomedical research.

We also have some lessons to learn from Europe, which has approved two gene therapies. The first, Glybera, which treats lipoprotein libase deficiency, did not meet market expectations. GlaxoSmithKline’s Strimvelus—approved this past summer for ADA-SCID , a rare condition in which children are born without a fully-functioning immune system—is priced at $665,000. In spite of the high cost, it arguably is preferable to have a curative treatment than to pay for ameliorative therapies that would persist a lifetime.

The Patient Journey and Challenges to Access

The journey for gene therapy patients presents several challenges to access, because it spans multiple treatment settings, different types of providers and varying payment models. Before patients become candidates for gene therapy, they have to be diagnosed with a genetically inherited disease. Then the cells containing the defective genes that are eligible for gene editing need to be extracted. The facilities that perform gene therapy services are limited and often some distance from where the patient lives, even outside the U.S. in some instances, requiring travel. After the gene modification, the corrected gene needs to be re-introduced into the patient, most often through a stem cell transplantation procedure. Again, only a few facilities perform these procedures. Finally, there’s the need for long-range medical monitoring.

How will insurance pay for these highly specialized therapies that span multiple treatment settings? Private employer-sponsored insurance and the Medicaid program are going to be the critical payers. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 48% of non-elderly adults and children are enrolled in employee-sponsored coverage. We need to distinguish, however, between coverage and payment. A patient may be technically covered but receive inadequate payment for the most expensive portions of gene therapy: the actual gene editing and transplantation procedures.

In addition, coverage is not guaranteed under private insurance, even when there are formal coverage policies. Coverage can be subject to medical necessity and other criteria , including specific conditions.

Payers typically review transplantation requests on a case-by-case basis. Payers usually receive transplantation requests from the facility and first do a check on the patient’s eligibility, determining whether the patient’s plan includes a coverage benefit for transplantation. Then, an internal packet of information is prepared for the medical director’s review. Occasionally, these types of requests may be elevated to the executive committee. Once a positive or negative determination is made, the payer communicates that decision to the facility, as well as to the insured member and his or her family.

Commercial payers negotiate contracts with transplantation centers of excellence (COEs) to be part of their networks and use financial incentives to drive patients to specific COEs. COEs and private insurers negotiate to determine which costs are included or excluded from the specific contracts. Ultimately, the COE’s patient outcomes are going be the most compelling factor to the payer during contract negotiations. One could consider transplantation the original value-based payment model, using all-inclusive contracts based on patient outcomes and upside/downside risks.

Medicaid Coverage and Payment

Across the nation, 39% of children aged 0–3 had Medicaid and CHIP coverage in 2014. More children than many realize are eligible to get Medicaid coverage. Children through age five are eligible for coverage if their families’ incomes are up to about 300% of the poverty level, which, for a family of three, is about $60,000 a year.

Medicaid has a different set of rules for benefit coverage depending on whether the patient is an adult or a child, with 21 being the demarcation point. Medicaid must cover certain services, such as hospital care; nursing facilities; and physician, clinical, laboratory, X-ray and family planning services. States also must cover Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) services.

For adults, prescription drug coverage is an optional benefit. For children, it is a required benefit, because of the stipulation that Medicaid must provide all medically necessary services to children, even if those services are not covered for adults. The definition of medical necessity is broader for children than for adults, including treatment to “correct or ameliorate” a condition.

States are not required, however, to cover experimental services. Therefore, most states do not include experimental treatments in their coverage. That raises the critical question of whether a treatment is considered experimental. At this time, the determination is left to the state. The federal government has put a guardrail in place, however: the state’s decision must be reasonable and based on the latest scientific information.

States can’t just say that all gene therapies are experimental. They must look at the evidence and, if they determine that a service is not experimental and is medically necessary for a particular child, then they must provide coverage. Like private payers, states have prior-authorization procedures, including looking at costs and exploring whether there are any alternative approaches that are equally efficacious but less expensive. They cannot, however, set service limits on children in the Medicaid program.

Medicaid Coverage for a Low-Income Child’s Gene Therapy

As discussed above, the state Medicaid agency will determine whether a service is covered or experimental. Even if a service is not outlined in the state’s Medicaid plan, it must be covered if it is not experimental and is medically necessary.

States have very broad discretion under the Medicaid program to set their payments for services. They have to make sure, however, that services are available to the Medicaid population to the same extent that they are available in the private sector. States can’t pick a payment rate that is inevitably going to exclude a service if that service is generally available in the private sector.

Much of the Medicaid program is delivered through managed care arrangements. In those situations, the state sets the overall payment rates to the managed care organization, and the managed care organization determines the payment rate for a particular service. Sometimes states will carve out very high-cost services from their managed care contracts. Decisions are made on a state-by-state basis.

Children With or Without Private Insurance May Qualify for Programs Under Medicaid

As mentioned earlier, the income eligibility level for Medicaid is 300% of the poverty level—but there are alternate routes to qualifying for Medicaid, depending on the state. (These additional avenues are not mandatory, though most states offer some or all of them.)

It is important to point out that the alternate sources of Medicaid coverage are not mutually exclusive to employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) coverage. Families can have ESI and still qualify for Medicaid, if they have a child with a significant medical problem. ESI would be the primary source of coverage, and Medicaid would pick up the difference.

The first alternate source is the medically needy program. It is an optional program for families whose incomes are above the normal income eligibility levels for Medicaid, but whose medical bills are extraordinary. The medically needy option allows people to “spend down” to the eligibility level of Medicaid. Once a family’s medical bills reach a certain percentage of its income, the family can qualify for Medicaid for a period of time, typically about six months

Another way that children with significant healthcare needs can get coverage through the Medicaid program if they don’t qualify based on family income is through waiver programs. The Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) waivers provide Medicaid coverage for adults and children who require an institutional level of care but instead opt to receive care at home. The Katie Beckett program is similar to HCBS but often has less strict eligibility requirements. These programs limit the number of adults and children who can be served. They are not entitlement programs like the rest of Medicaid.

Finally, institutional Medicaid provides another avenue of eligibility for children who have been institutionalized or need to remain in the hospital after birth. Once a child has been in the hospital for at least 30 days, his or her family can apply for Medicaid on behalf of the child. In these cases, the family’s income is not counted.

It’s important to note that families have appeal remedies if there is a denial of coverage. They also can work with advocacy groups, gene therapy companies, and their personal physicians to influence a coverage decision with the Medicaid agency.

Payment Models

There are few analogues in the marketplace that serve as predictors of how gene therapy might be paid for and covered. Possibilities include non-traditional financial models, risk-sharing with transplant facilities, payment for outcomes, and reinsurance across states and employers. For example, if a state is hit with three or four gene therapy cases, is there a way to create some sort of multi-state reinsurance program?

There is also some thinking around a federal Medicaid match—enhanced federal matching for gene therapy and/or amortization of what would have been the federal match for the ameliorative treatment as a substitute for the higher-cost curative treatment. In addition, there is some initial exploration of designing social impact bonds, wherein private investors can choose to make a long-term investment in a patient’s health. As gene therapies reach larger populations, payment will get increasingly complicated, and we’ll need to explore innovative approaches.

The OIG’s Medicare Agenda for 2017

By Robert Belfort, Partner, Manatt Health | Randi Seigel, Counsel, Manatt Health | Alex Dworkowitz, Associate, Manatt Health

The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued its annual work plan (2017 Work Plan) on November 10, 2016, which, as in previous years, summarizes new and ongoing areas of regulatory review and indicates the OIG’s focus in the coming year. Healthcare organizations should utilize the 2017 Work Plan as a tool when reviewing their internal audit and compliance plans and performing their annual risk assessments.

Medicare Parts A and B

The OIG once again set forth an extensive list of priorities for hospitals in 2017, many of which are continuations from the 2016 Work Plan. The OIG has four new initiatives for hospitals this year.

- HBO Therapy. The OIG will review provider reimbursement for hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy services to determine whether Medicare payments were in compliance with federal regulations. The OIG added this to the 2017 Work Plan because prior reports raised concerns that beneficiaries had been treated with HBO therapy services for non-covered conditions, the medical documentation did not adequately support such treatments, and beneficiaries received medically unnecessary treatments.

- DSH Payments. The OIG will assess whether Medicare Administrative Contractors are properly settling Medicare costs reports with respect to disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments. Medicare pays hospitals DSH payments based on the number of Medicaid patient days a hospital furnishes. Because Medicare DSH payments are determined using a complex methodology, the OIG believes these payments pose a high risk of overpayment.

- Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Outlier Payments. Due to a 28 percent increase in the number of inpatient psychiatric facility claims with outlier payments from 2014 to 2015, the OIG will determine whether inpatient psychiatric facilities complied with Medicare documentation, coverage and coding requirements for stays that resulted in outlier payments.

- Inpatient Rehabilitation Hospitals. The OIG will conduct a study to assess a sample of rehabilitation hospital admissions to determine whether the patients participated in and benefited from intensive therapy.

In addition, the OIG has revised several of its prior initiatives for hospitals. The OIG continues to include intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the 2017 Work Plan. The OIG’s previous reviews identified that IMRT was often incorrectly billed by hospitals. Accordingly the OIG intends to review IMRT to ensure that the two phases of IMRT—planning and delivery—were billed appropriately.

Hospital outlier payments continue to be a focal point of the OIG. The OIG has retained a review related to hospital outpatient outlier claims that was introduced in the Mid-Year 2016 OIG Workplan. The OIG intends to evaluate the extent of potential Medicare savings if hospital outpatient stays were ineligible for an outlier payment.

In addition, the OIG will review Medicare inpatient outlier payments to hospitals to determine whether the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) performed necessary cost-to-charge ratio reconciliations in a timely manner to enable Medicare contractors to perform final settlement of the hospitals’ associated cost reports. The OIG also will evaluate whether the Medicare contractors referred all hospitals that met the criteria for outlier reconciliations to CMS.

The OIG has shifted its prior year’s broad focus on oversight of provider-based status to a narrower review comparing Medicare payments for physician office visits in provider-based clinics and freestanding clinics. This review will determine the difference in payments made to the clinics for similar procedures. The OIG also will assess the potential impact on Medicare and beneficiaries of hospitals claiming provider-based status for such facilities.

The OIG has kept on the 2017 Work Plan with no change from prior years a determination of how hospitals’ use of outpatient and inpatient stays changed under Medicare’s two-midnight rule by comparing claims for hospital stays in the year prior to and the year following the effective date of that rule.

Also remaining on the 2017 Work Plan are reviews of the following:

- Medicare claims compared to Medicare costs resulting from additional use of medical services associated with defective or recalled medical devices.

- Whether Medicare made reduced payments for replaced medical devices as required.

- Whether Medicare payments for dental services were appropriate. The OIG will roll up the results of these audits of Medicare hospital outpatient payments for dental services to provide CMS with cumulative results and make recommendations for any appropriate changes to the program.

- Direct graduate medical education (DGME) costs to determine whether hospitals received duplicate or excessive DGME payments due to incorrect counting of interns or residents. The OIG, as part of this review, also will assess the effectiveness of the Intern and Resident Information System in preventing duplicate payments for DGME costs.

- Medicare payments to hospitals nationwide for outpatient right-heart catheterizations and endomyocardial biopsies performed to determine whether any were performed and billed for during the same patient encounter.

- Medicare payments to hospitals for claims that include a diagnosis of kwashiorkor (a rare, severe condition) to determine whether the diagnosis is adequately supported by documentation in the medical record.

- Hospital controls over the reporting of wage data used to calculate wage indexes for Medicare payments.

- CMS-validated hospital inpatient quality data and reporting to determine whether the data are accurate and complete.

- Medicare payments to determine whether Medicare inappropriately paid for overlapping claims when a beneficiary was an inpatient of one hospital and then sent to another hospital to obtain outpatient services that were not available at the originating hospital.

- Medicare payments to acute care hospitals to determine hospitals’ compliance with selected billing requirements and recommend recovery of overpayments.

- Hospitals’ efforts to prepare for the possibility of public health emergencies resulting from emerging infectious disease threats, determine hospitals’ use of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) resources, and identify lessons and challenges that hospitals face as they prepare to respond to emerging infectious disease threats such as Ebola.

- National incidence of adverse and temporary harm events for Medicare beneficiaries receiving care in Long-Term Care Hospitals; identify factors contributing to these events and determine the extent to which the events were preventable.

Medicare Advantage and Part D

The OIG announced numerous audits and evaluations relating to spending and access to care under Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D. While Medicare Advantage represents a larger share of federal spending, more items in the work plan focus on issues on the Part D side.

- Risk-Adjustment Data Supporting Diagnoses: The question of whether risk-adjustment data submitted by Medicare Advantage Organizations (MAOs) is accurate has been in the spotlight for the past several years, and the OIG plans to continue work in this area. The OIG plans to review medical record documentation to determine whether such documentation supports the diagnoses that MAOs submit to CMS and whether the diagnoses comply with federal requirements.

- Extent of Denied Care: Out of concern that MAOs may be denying medically necessary care, OIG will determine the extent to which Part C services were denied, appealed or overturned from 2013 to 2015. As part of this work, the OIG will examine whether some MAOs had higher rates of denials and appeals than others during this period.

- Payments for Service Dates After Date of Death: A 2013 OIG analysis found that CMS made $20 million in improper payments to MAOs and $1 million in improper payments to Part D sponsors for providing coverage after the date of a beneficiary’s death. The OIG plans to follow up on this work and examine the extent to which CMS continues to make such improper payments.

- Payment Rates for Brand-Name Drugs: Reimbursement rates for popular brand-name drugs have increased in recent years, with the OIG noting that prices for the most commonly used brand-name drugs increased 13 percent in 2013 alone under Part D. OIG will conduct an analysis of changes in pharmacy reimbursement rates for brand-name drugs under Part D from 2011 through 2015.

- Compounded Topical Drugs: According to the OIG, Part D spending on compounded topical drugs grew by more than 3,400 percent from 2006 to 2015, indicating a potential fraud risk. The OIG will review billing for these drugs and will identify any pharmacies with questionable billing practices for such drugs.

- Part D Pharmacies Not Enrolled in Original Medicare: Currently, pharmacies that dispense Part D drugs are not required to enroll in original Medicare. (Such pharmacies may enroll if they bill original Medicare for Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics/Orthotics and Supplies (DMEPOS) , among other reasons.) The OIG is concerned that some pharmacies may be engaging in Part D fraud, and the lack of an enrollment requirement may be enabling such fraud. The OIG will examine the extent to which pharmacies that bill for Part D drugs, particularly high-risk pharmacies, are enrolled in original Medicare.

- Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Conflicts of Interest: Prior OIG work concluded that CMS did not adequately monitor potential conflicts of interest among individuals who sit on Part D sponsors’ Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committees. The OIG will reexamine this issue to determine what steps CMS and Part D sponsors have taken to improve oversight of these conflicts.

- Dual Eligibles’ Access to Drugs: The OIG will examine the extent to which drug formularies used by Part D sponsors include drugs commonly used by dual-eligible beneficiaries. (This study is required by Section 3313 of the Affordable Care Act.)

- Part D Catastrophic Coverage Payments: The OIG will examine trends in CMS’s reinsurance subsidy payments to Part D sponsors from 2010 to 2014.

- Rebates for Drugs Dispensed Through 340B Entities: The OIG will estimate the upper boundary of what could be saved if pharmaceutical manufacturers were required to pay rebates for Part D drugs dispensed at 340B covered entities.

- Integrity of Encounter, Prescription Drug Event, and Coverage Gap Discount Data: The OIG will examine the extent to which encounter data (Part C) and prescription drug event data (Part D) submitted by MAOs and drug plan sponsors were accurate and adequately supported by documentation. The OIG also will review the accuracy of data submitted by plan sponsors under the coverage gap discount program.

Conclusion

As always, the OIG has noted that the 2017 Work Plan is an ongoing and evolving process, and the 2017 Work Plan may be updated throughout the year. The new administration will also likely have an effect on the OIG’s priorities. The 2017 Work Plan is available here.

OCR Issues New FAQs on the ACA’s Non-Discrimination Provision

By Michael Kolber, Associate, Manatt Health

Earlier this year, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights (OCR) issued final rules on Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, age, disability, race, color or national origin in any federally funded healthcare programs or activities. The major substantive change in Section 1557 is prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex by covered entities. (Other civil rights laws already prohibited discrimination on other bases.) The final rules also include significant new notice and process requirements that many covered entities have had a difficult time understanding, leading to compliance challenges. The notice requirements became applicable in October and apply to all health plans, providers and other entities that receive federal dollars for health programs or activities (with some caveats).

OCR has been continuing to issue new guidance to clarify the notice requirements but has not been announcing when new guidance is available. Therefore, the guidance has received little attention. Last month, OCR provided some clarification on Section 1557, issuing new FAQs saying that any significant communication or publication that appears on a 8.5 x 11 piece of paper must include a full nondiscrimination notice and fifteen non-English taglines, not the short nondiscrimination statement (and two taglines) that applies to “small-sized” significant communications or publications. This is inconsistent with what the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has said in the past and may be disruptive to covered entities. CMS previously told Medicare Advantage organizations that the Star Rating information document, which typically appears on a 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper, as well as other documents that appear on one side of a sheet of paper, can be considered “small sized.”

In the new guidance, OCR also said that Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy notices are required to have a Section 1557 nondiscrimination notice. OCR exempted outdoor or broadcast advertising from the requirement to include a nondiscrimination notice.

The New FAQs

Below are the added FAQs. To review all of the FAQs, click here. If you have questions or need additional guidance, please contact Michael Kolber at 212.790.4568 or mkolber@manatt.com.

Q. What is the date by which a covered entity must comply with the posting requirements in § 92.8 of the Section 1557 regulation?

A. The effective date for these specific requirements was October 17, 2016[1]. In general, covered entities may satisfy these requirements either by including the required notice and taglines on the significant publication or communication itself or by creating an insert to be enclosed with the publication or communication. For covered entities with current stock of hard copy significant publications and communications that were printed before the effective date of the Section 1557 regulation (July 18, 2016), such entities may exhaust existing stock but should consider enclosing an insert of the required notice and taglines with the publication or communication.

Q. Section 1557 and its implementing regulation (Section 1557) require covered entities to post—in their significant publications and communications—nondiscrimination notices in English, as well as taglines in at least the top 15 languages spoken by individuals with limited English proficiency (LEP) in the State(s) served [2]. What are some examples of documents that are not considered significant publications or communications?

A. The following are not significant publications and significant communications under Section 1557:

- Radio or television ads;

- Identification cards (used to access benefits or services);

- Appointment cards;

- Business cards;

- Banners and banner-like ads;

- Envelopes; or

- Outdoor advertising, such as billboard ads.

Q. For significant publications and communications that are small-sized, covered entities must post at least a nondiscrimination statement in English and taglines in at least the top two languages spoken by individuals with LEP of the State(s) served[3]. What are publications and communications that are small-sized?

A. Examples of documents that are “small-sized” include:

- Postcards,

- Tri-fold brochures, and

- Pamphlets.

Significant publications and significant communications that are presented on 8.5 x 11 inch paper are not considered “small-sized,” even if the information conveyed fits on one side of a page.

Q. Is the Notice of Privacy Practices required by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule at 45 C.F.R. § 164.520 a communication that is “significant” under § 92.8 of the Section 1557 regulation? If so, does a Section 1557 covered entity’s inclusion of the nondiscrimination notice and taglines with the entity’s Notice of Privacy Practices constitute a “material change,”[4] thus requiring the entity to promptly revise and distribute its Notice of Privacy Practices?

A. The Notice of Privacy Practices required by the HIPAA Privacy Rule is a communication that is “significant” under § 92.8 of the Section 1557 regulation. The inclusion of the Section 1557 nondiscrimination notice and taglines with the entity’s Notice of Privacy Practices does not constitute a “material change” of that entity’s Notice of Privacy Practices. Section 1557’s nondiscrimination notice advises individuals of their Section 1557 civil rights and therefore does not constitute a change in privacy policies and practices regulated under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Therefore, revision and distribution, in accordance with 45 C.F.R. § 164.520, of an entity’s Notice of Privacy Practices is not required.

Q. Is the written Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC) required by 45 C.F.R. § 147.200(a) a publication that is “significant” under § 92.8 of the Section 1557 regulation? If so, Federal regulations limit the SBC’s length to four double-sided pages[5]. Does a Section 1557 covered entity’s inclusion of the nondiscrimination notice and taglines with its SBC count against the regulatory page limit?

A. The written summary of benefits and coverage required by 45 C.F.R. § 147.200(a) is a publication that is “significant” under § 92.8 of the Section 1557 regulation. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires the use of an addendum to the SBC to accommodate applicable language access standards[6]. Accordingly, covered entities required to provide a SBC must include the nondiscrimination notice and taglines required by § 92.8(b)(1), (d)(1) in its addendum along with other applicable language access standards. This addendum must contain only the Section 1557 nondiscrimination notice and taglines and other applicable language access information.

New Manatt Webinar, “Election 2016: Strategic Implications for Healthcare.”

Click Here to Register Free—and Find Out What a Trump Administration Means for Healthcare.

Election 2016 is over, and Donald Trump is the president-elect. Republicans maintain control of the House and the Senate—and now have 33 governors and control 70 of 99 state legislative bodies. What does the Republican sweep mean for healthcare at the federal and state levels? Which provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are at risk and which are likely to remain? What can you expect to happen as a new administration takes office—and how can you prepare your organization?

Manatt Health provides the answers in a new webinar that reveals the key takeaways from the election—and helps you anticipate and plan for the changes that lie ahead. Scheduled for January 12 from 1:00 – 2:00 p.m. ET, the session will give you the opportunity to:

- Understand the healthcare positions, goals and legislative/policy backgrounds of key appointees—and their potential impact.

- Explore the post-election implications at both the federal and state levels.

- Get the bottom line on what’s likely to happen to ACA and post-ACA reforms and fundamental health system trends.

- Analyze President-elect Trump’s healthcare agenda and competing priorities.

- Examine likely administrative and legislative actions across a range of issues, including drug costs, Medicare, reproductive health and employer coverage.

- Identify “repeal and replace” policy options, including the key components of a replacement strategy and the hurdles to achieving replacement quickly.

- Look ahead at likely Medicaid administrative actions—and challenges to expansion.

- Track key events coming up this year—from the expiration of CHIP to pending decisions on the insurance company mergers, cost-sharing reductions and risk-adjustment payments.

With potentially vast changes on the horizon, this is a program you can’t afford to miss. Even if you can’t make the original airing on January 12, click here to register free now and receive a link to view the webinar on demand.

Presenters:

Joel Ario, Managing Director, Manatt Health

Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, Managing Director, Manatt Health

Decisions Regarding Hospice Care for Isolated Patients

By Randi Seigel, Counsel, Manatt Health | Timothy Kirk, PhD, Associate Professor of Philosophy, City University of New York (CUNY), York College

Editor’s Note: In September 2010, New York adopted the Family Health Care Decisions Act (FHCDA), establishing the authority of a patient’s family member or close friend (referred to as a surrogate) to make healthcare decisions when a patient lacks decision-making capacity, has not executed a proxy appointing a healthcare agent, and does not have a guardian. In 2011, the FHCDA was amended to allow surrogate decision-making for hospice patients. A 2015 amendment to the FHCDA provides a process through which physicians, acting under the standards that apply to surrogates, can elect the hospice benefit and consent to a hospice plan of care for “isolated” or “unbefriended” patients.

In a new article for the New York State Bar Association Health Law Journal, summarized below, Manatt Health’s Randi Seigel teams with Timothy Kirk, associate professor at CUNY’s York College, to explain the context and content of the amendment and present considerations on its implementation. Click here to download a free PDF of the full article. (The article is reprinted with the permission of the Health Law Journal, Winter 2016, Vol. 21, No. 3., published by the New York State Bar Association, One Elk Street, Albany, New York, 12207.)

__________________________________________________

The FHCDA, Isolated Patients and Hospice Care

Isolated patients are patients who (1) lack decision-making capacity, (2) have not appointed a healthcare agent or for whom the agent is unable or unwilling to serve, and (3) have no surrogate reasonably available to make decisions. Estimates of isolated patients vary but a widely cited figure is three to four percent of nursing home residents nationally.

While the FHCDA does contain a provision permitting an attending and concurring physician to make healthcare decisions for isolated patients, two perceived barriers to using this process for decisions regarding hospice care produced reluctance in most New York State hospice providers to admit and care for isolated patients prior to the 2015 amendment.

First, there was a lack of clarity regarding whether provisions in PHL § 2994-g authorized an attending physician to elect the hospice care benefit and admit an isolated patient to a hospice care program. While the applicable Medicare regulation permits a patient representative to elect the hospice care benefit and admit a patient to hospice care, it defers to applicable state law when defining who may serve as a representative for a patient who is unable to elect the benefit because he or she is mentally or physically incapacitated. In New York State, the most commonly applicable law is the FHCDA. While some argued that the decision to commence hospice care could reasonably be considered a care decision for which PHL § 2994-g provided sufficient guidance, others argued that the hospice care benefit did not clearly fit into any of the three categories of treatment decisions for isolated patients covered by § 2994-g: routine medical treatment, major medical treatment, or decisions to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment.

Second, there was the matter of whether decisions by attending physicians to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment for isolated patients could reasonably be made in a hospice environment. Prior to the 2015 amendment, decisions in this category—including “do not resuscitate” orders—used criteria that were exceedingly difficult to satisfy.

Overview of the 2015 Amendment

The 2015 amendment to the FHCDA addressed both of these perceived barriers by making two changes:

- It added a new subsection (PHL § 2994-g (5a)) which provides a three-step process for making decisions regarding hospice care for isolated patients and clarifies the criteria for guiding those decisions.

- It repealed PHL § 2994-g(5)(c), which had directed the selection of a second physician to concur on decisions regarding hospice care for isolated patients in hospitals and residential healthcare facilities. Revised direction is now included in PHL § 2994-g (5a).

The 2015 Amendment: The Three-Step Care Decision Process

PHL § 2994-g (5a) presents a three-step process for making decisions regarding hospice care:

- Step 1: A patient’s attending physician considers options available for a decision regarding hospice care and selects the option most appropriate for the patient per PHL § 2994-d (4-5).

- Step 2: The concurring physician reviews the decision made by the attending physician and confirms it was made consistent with the criteria in PHL § 2994-d (4-5).

- Step 3: The ethics review committee reviews the decisions made by the attending and concurring physicians and confirms they were made consistent with the criteria in § 2994-d (4-5).

The amended language in § 2994-g (5a) makes it clear that the three-step process also applies to the decision to elect the hospice insurance benefit, authorizing attending physicians in their role as surrogate to “execute appropriate documents for such decisions (including a hospice election form) for an adult patient who is hospice eligible.” As such, the first of the two perceived barriers to hospice care for isolated patients has been removed.

The 2015 Amendment: The Criteria for Decisions Regarding Hospice Care

Because it applies to all decisions regarding hospice care, the amended text of PHL § 2994-g (5a) also effectively changes the criteria used when making decisions regarding major medical and life-sustaining treatment for isolated patients when the decisions are part of a hospice plan of care. The amendment alters the threshold which must be met in making decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapies. As discussed above, the threshold in § 2994-g(5) was rarely met. The criteria in § 2994-d (5)—used by FHCDA surrogates when deciding to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment—are more consistent with the goals of hospice care and the preferences of many (but not all) hospice patients. Similarly, decisions regarding major medical care must also move through the three-step process when they are part of a hospice plan of care.

While the 2015 amendment removed a barrier to the election of hospice care for isolated patients and established a more reasonable decision-making standard for life-sustaining treatment when part of a hospice plan of care, it may actually have created a burdensome process for making decisions around routine medical decisions. The three-part decision process applies to all decisions regarding hospice care. Because of the detailed and comprehensive nature of a formal hospice plan of care, most routine medical treatment decisions—including ones as small and frequent as adjusting medication orders—require a change to the plan of care. Therefore, a literal reading of PHL § 2994-g (5a) would necessitate engaging the three-step process, including the Ethics Committee review, for each routine medical treatment decision.

As the intention of the 2015 amendment was to break down barriers to accessing hospice care for isolated patients, it is consistent with this intention to infer that it was not the aim of the Legislature to bog down decision-making for routine medical care. Rather, it is reasonable to posit that an isolated hospice patient’s attending physician, acting as surrogate, is permitted to make routine treatment decisions in consultation with the patient’s interdisciplinary care team without engaging the three-step process.

Implementing the 2015 FHCDA Amendment

When implementing the 2015 FHCDA amendment, it’s helpful to review the overall FHCDA requirements for healthcare decision making by surrogates; review current organizational policies and procedures guiding decision making by healthcare surrogates and the level of compliance; and integrate the amendment’s requirements into pre-existing organizational policies, procedures and practices. Whether integration is preferable to developing new policies, procedures and practices will depend on the strength of an organization’s infrastructure and a needs assessment conducted jointly with each client.

To ensure consistency of isolated patients’ access to hospice care and maintain compliance with the FHCDA, applicable state and federal conditions of participation and licensure requirements, it’s imperative to address these matters at the policy and procedure level rather than on an ad hoc basis. In addition, given the ambiguity left in the FHCDA for routine medical treatment decisions, a hospice organization can better defend its approach to how these decisions are made for isolated patients if it has a systematic, thoughtful method that is applied to all decisions made for isolated patients.

Now You Have a Second Chance to Benefit From “Connecting Medicaid Beneficiaries to Social Supports: The Critical Role of MCOs.”

Click Here to View the Program Free, On Demand—and Here to Download a Free PDF of the Presentation.

On December 7, Manatt Health and the Anthem Public Policy Institute co-hosted a new webinar examining the growing role of Medicaid managed care in addressing the social and economic challenges affecting health outcomes for patients with a mental health and/or substance use disorder (MH/SUD) diagnosis. We want to be sure you don’t miss the important information shared during the program. If you or anyone on your team couldn’t participate in the session—or want to view it again—click here to access it free on demand. If you would like to download a free copy of the presentation for your continued reference, click here.

Drawing on a new white paper from the Anthem Public Policy Institute that explores the importance of Medicaid managed care in providing social supports to MH/SUD patients, the webinar:

- Analyzes the role of socioeconomic factors in driving health outcomes.

- Shares new research that highlights the importance of facilitating access to social supports.

- Reveals emerging best practices among Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) and states in linking beneficiaries to social supports, including housing assistance, peer supports, education, employment and vocational training.

- Discusses the part social supports play in improving the stability, resiliency and recovery of MH/SUD patients.

The new white paper on which the webinar was based is part of an Anthem Public Policy Institute series that looks at the approaches to and benefits of integrating physical health, mental health and substance use disorder benefits, as well as related areas of managed care innovation. To access the full white paper series, click here.

If you have questions—or issues specific to your organization that you’d like to discuss—please reach out to Jon Glaudemans, Managing Director, Manatt Health at jglaudemans@manatt.com or 202.585.6524.

Presenters:

Jon Glaudemans, Director, Manatt Health

Jana Dreyzehner, MD, Behavioral Health Medical Director, Amerigroup, TN

Merrill Friedman, Senior Director for Disability Policy Engagement, Anthem, Inc.

Mary Shelton, Director, Behavioral Health Operations Bureau of TennCare

OIG Issues Final Rules Establishing New Anti-Kickback Statute Safe Harbors and Civil Monetary Penalties Law Exceptions

By Robert Belfort, Partner, Manatt Health | Julia Smith, Associate, Manatt Health

On December 7, 2016, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued two fraud and abuse final rules that have been pending for over two years. The first rule modifies and adds new safe harbors and exceptions to the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL), respectively. The second rule implements provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to clarify liability under several laws within the OIG’s jurisdiction, including the CMPL and the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA). Below we review the key takeaways.

A New Transportation Safe Harbor to the AKS

In the proposed rule1, the OIG established a safe harbor for an activity that has long been of interest to providers: the provision of free or discounted transportation to patients. In several prior advisory opinions, the OIG authorized providers to offer transportation to patients if certain safeguards were employed. The final rule builds on that guidance and sets forth several requirements for provider transportation programs. Following are the critical elements of the safe harbor:

- Most healthcare providers and payers can supply transportation. Pharmaceutical and durable medical equipment companies cannot. The safe harbor allows entities that primarily supply healthcare services, including hospitals, physicians, accountable care organizations, home health agencies, health plans and laboratories, to provide transportation. Entities that primarily supply healthcare items, such as pharmaceutical manufacturers and durable medical equipment companies, are not covered by the safe harbor.

- The entity making the transportation available must bear the full cost. The cost of the transportation must be borne by the entity that makes it available. The cost cannot be shifted to any Federal healthcare program, other payers or individuals.

- Providers may only supply transportation to established patients. The safe harbor protects transportation provided to an established patient, defined as a person who has previously attended an appointment with a provider or supplier or selected and initiated contact to schedule an appointment with the provider or supplier.

- Transportation must be to obtain medically necessary healthcare. The OIG solicited comments on whether it should permit transportation to locations that relate to the patient’s health, such as an appointment to apply for government benefits, but ultimately opted to limit the safe harbor to transportation to obtain medically necessary items and services.

- Transportation must be local. The transportation must be confined to within 25 miles of the healthcare provider or supplier from which the individual is being transported, or within 50 miles if the patient resides in a rural area.

- There must be a uniform policy on who is offered transportation, and no tie to the volume or value of referrals. That policy must apply uniformly and consistently and cannot be tied to the volume or value of referrals for items or services covered by federal healthcare programs.

- Air or ambulance transportation is not covered. Public transportation is. Third-party transportation (including public transportation) is covered by the safe harbor, as is transportation in vehicles equipped with wheelchairs. Air, luxury and ambulance transportation are not covered.

- Marketing of transportation services is prohibited. The transportation assistance may not be publicly advertised or marketed, no marketing of healthcare items or services may occur during the course of the transportation, and drivers may not be paid per beneficiary transported. Informing patients that transportation is available in a targeted manner is not marketing.

- Shuttle services may be provided with fewer restrictions. A separate provision of the rule permits the furnishing of shuttle services by the same entities authorized to make available other forms of transportation. The rule defines a shuttle as “a vehicle that runs on a set route, on a set schedule.” Shuttles are not restricted to carrying established patients, and there are no requirements on where a shuttle can and cannot make stops, as long as it runs on a set route, follows a set schedule and is confined to the local area. The marketing restrictions applicable to non-shuttle transportation apply to shuttles as well.

MMA and ACA Provisions Related to the AKS Are Codified

In addition to establishing the local transportation safe harbor, the final rule codified several statutory provisions that were included in the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) and the ACA. These provisions consist of:

- Pharmacy cost-sharing waivers: Pharmacies may waive cost sharing on Medicare Part D drugs if the pharmacy does not offer the waiver as part of an advertisement or solicitation, does not routinely offer such waivers, and waives cost sharing only after determining the patient has a financial need or after having undertaken reasonable collection efforts. If the patient qualifies for the low-income subsidy, then pharmacies can waive cost sharing so long as the waiver is not advertised or solicited.

- Federally qualified health center payments: Medicare Advantage Organization payments to federally qualified health centers are permissible under the AKS, as long as those payments are pursuant to a written agreement.

- Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program: Point-of-sale discounts offered by pharmaceutical companies to Medicare Part D beneficiaries fall under this safe harbor so long as the discounts comply with the terms of the coverage gap program.

The Gainsharing Provision of the CMPL

In the proposed rule, the OIG sought comments on the proper interpretation of the gainsharing provision of the CMPL, which at the time prohibited hospitals from knowingly paying a physician to “reduce or limit services” provided to Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries under the physician’s care. The interpretative question on which the OIG sought comment—whether the provision bars payments to reduce medically unnecessary services—was rendered moot by Congress in 2015, when it added the words “medically necessary” before services, making it clear that payments to reduce medically unnecessary services are not prohibited by the provision. The final rule does not codify this statutory change, but it is self-implementing.

Interpreting New Statutory Exceptions to the Anti-Inducement Provision of the CMPL

The final rule also codified and provided guidance on the implementation of four new statutory exceptions to the anti-inducement provision of the CMPL added by the ACA.

- Remuneration that promotes access to care and poses a low risk of harm: In a somewhat vague sentence, the ACA exempts from the anti-inducement provision “any other remuneration which promotes access to care and poses a low risk of harm to patients and Federal healthcare programs.” In the final rule, the OIG defined the foregoing as remuneration that “improves a beneficiary’s ability to obtain items and services payable by Medicare or Medicaid” and poses a low risk of harm in that it is unlikely to skew clinical decision making, is unlikely to increase Federal healthcare program costs through overutilization or inappropriate utilization, and does not raise safety or quality concerns. In the preamble to the final rule, the OIG provided additional guidance on how it will interpret the rule, announcing that remuneration that rewards patients for accessing care or complying with a treatment plan will not be protected by the exception (e.g., no movie tickets for attending smoking cessation counseling sessions) on the grounds that such remuneration does not improve a beneficiary’s ability to obtain medically necessary items and services. However, remuneration that removes impediments or otherwise facilitates a patient in accessing care or complying with a treatment plan (e.g., free child care during appointments, lodging assistance for a hospital visit, or a low-cost fitness tracker) may be covered by the exception, provided that they also pose a low risk of harm.

- Nominal value: Items of nominal value do not require an exception. New policy was announced concurrent with the rule that increased the interpretation of “nominal” from no more than $10 in value individually or $50 in aggregate annually per patient, to $15 and $75, respectively.

- Retailer rewards: The rule also codified an exception that the ACA added to the CMPL allowing retailers to provide free or discounted healthcare as part of a retailer rewards program. Under the exception, a) the discounted items or services must consist of coupons, rebates or other rewards from a retailer; b) the rewards must be offered on equal terms to the general public, regardless of health insurance status; and c) the rewards cannot be “tied to the provision of other items or services” reimbursed by Medicare or a state healthcare program.

- Remuneration based on financial need: The final rule largely mirrors the statutory text, which mandates that: a) the items or services not be advertised, b) the items and services not be tied to the provision of services reimbursed by Medicare or a state healthcare program, c) there is a reasonable connection between the items and services and the patient’s medical care, and d) the patient have a financial need. In the rule, OIG clarified that the remuneration must be reasonable from a medical and financial perspective and provided examples to illustrate how it will interpret this requirement. (For example, a low-cost fitness tracker may be reasonable; an electronic tablet that allows individuals to access health-related apps would not be reasonable.)

- Cost-sharing waivers for the first fill of generic drugs: The OIG rule allows Part D plan sponsors to waive cost sharing for the first fill of a covered generic drug, including an authorized generic drug. The rule provides that sponsors who wish to offer these waivers must disclose this incentive program in their benefit plan package submissions to CMS for coverage years beginning on or after January 1, 2018.

Codification of Civil Monetary Penalties Established by the ACA

The ACA established penalties, assessments and exclusions for failing to grant the OIG timely access to records, ordering or prescribing while excluded from a Federal healthcare program, making false statements on an application to participate in a Federal healthcare program, failing to report and return an overpayment, and making or using a false record or statement that is material to a false claim. These statutory changes are codified in the second final rule issued by OIG. The rule also codified an ACA provision that imposed penalties and assessments on a contracting organization of a Medicare Advantage or Part D plan that enrolled an individual in a plan or transferred an individual from one plan to another without his or her consent, or that failed to comply with applicable marketing restrictions.

Factors for Determining Penalty and Assessment Amounts and Period of Exclusion for CMP Violations

The OIG clarified and revised the factors it will consider when determining exclusion periods and the amount of penalties and assessments to impose for CMP violations. The existing rule listed factors for certain violations in one section and provided additional details in another. The new rule provides a single list of primary factors applicable to all CMP violations, except as otherwise provided. These are: (1) the nature and circumstances of the violation, (2) culpability, (3) history of prior offenses, (4) other wrongful conduct, and (5) “other matters as justice may require.” The new rule also adds as a mitigating factor an entity’s disclosure to the OIG through the Self-Disclosure Protocol or to CMS through the Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol for Stark Violations, as well as disclosure to CMS of EMTALA violations prior to CMS receiving a complaint regarding the violation or otherwise learning of it.

In addition, the OIG increased the claims-mitigating factor, which is applied when the violations did not result in significant monetary losses by Federal healthcare programs, from $1,000 in program losses to $5,000. The OIG also revised the claims-aggravating factor, which was previously applied when the program losses were “substantial,” to specify that the factor shall be applied for violations causing $50,000 or more in program losses.

Methodology for Calculating Penalties and Assessments

In the proposed rule, the OIG proposed new methodologies for calculating the penalties and assessments imposed under the CMPL, some of which triggered significant opposition from stakeholders and were not included in the final rule. For example, the OIG proposed that where an excluded person participated in the provision of billable items and services but those items or services were not separately billable, the penalties should be based on the number of days the person was employed by the billing entity. That proposal was not adopted in the final rule, which states that the penalty will be based on each item or service provided by the excluded person, and the assessment will be based on the cost to the entity of employing the excluded person. Where the items and services are separately billable, the penalties and assessments will be based on the number and value of the items and services billed.

In the proposed rule, the OIG also proposed interpreting the statutory penalty for failure to report and return an overpayment by the deadline as up to $10,000 per day. In the final rule, it opted to interpret the statute as permitting a penalty of up to $10,000 per item or service, as many commenters had requested.

EMTALA Liability

The final rule provides several updates to the EMTALA CMP regulations, including clarifying the circumstances in which an on-call physician will be liable under the Act, and revising the list of aggravating and mitigating factors that OIG will consider in its enforcement of EMTALA.

1Office of Inspector General; Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse, Revisions to Safe Harbors Under the Anti-Kickback Statute, and Civil Monetary Penalty Rules Regarding Beneficiary Inducements and Gainsharing, 79 Fed. Reg. 59717 (October 3, 2014).

Where Are Subsidy-Eligible Enrollees Most Vulnerable to Losing Coverage?

By Valerie Barton, Managing Director, Manatt Health | April Grady, Senior Manager, Manatt Health | Jessica Nysenbaum, Senior Manager, Manatt Health | Harsha Prabhala, Consultant, Manatt Health

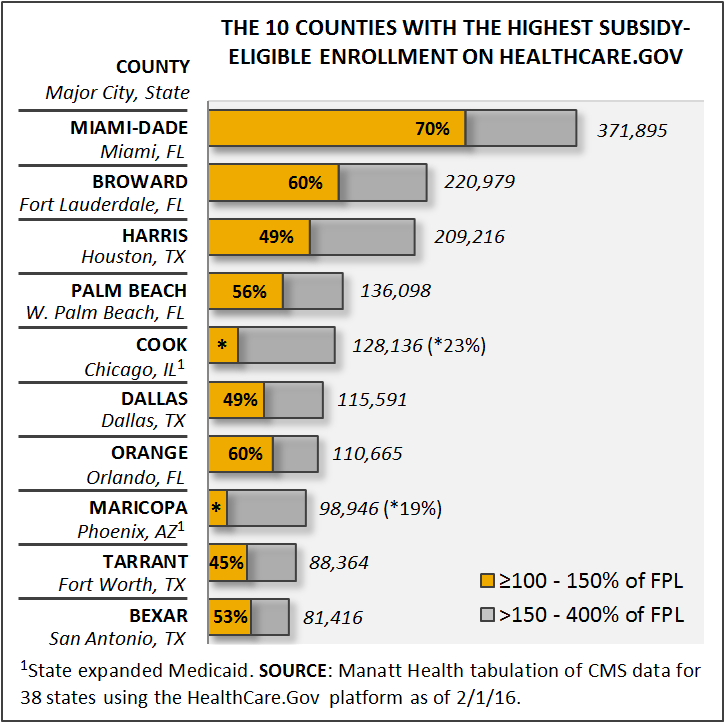

In the event that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is repealed, subsidy-eligible enrollees across the country are at risk of losing affordable health insurance options. Without subsidies, Americans with incomes falling between 100% and 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL)—those who are least likely to afford rising premiums without assistance—are the most vulnerable to losing their coverage.

Where is the potential loss of health insurance coverage most significant? Manatt Health analyzed county-level data from the 38 states using the Healthcare.gov federal platform and identified the 10 counties with the highest number of subsidy-eligible enrollees. Nearly half of those who are subsidy eligible fall into the lowest-income bracket and would be most impacted by the lack of affordable health insurance coverage. The chart below captures our findings.

The 10 Counties with the Highest Subsidy-Eligible Enrollment in Healthcare.gov

Note that since Illinois and Arizona have expanded Medicaid, a higher percentage of people in the lowest-income bracket are covered through the Medicaid program. However, the total number of people receiving subsidies, all of whom are at risk of losing coverage, is still high enough to place them in the top 10.

Antitrust Corner: Telehealth for Healthy Competition

By Lisl Dunlop, Partner, Antitrust and Competition

As providers look for more convenient and cost-effective means to reach patients, there has been much discussion about the potential benefits of telehealth services. Such services also are healthy from an antitrust perspective. Against a backdrop of regular advocacy in favor of lowering barriers to the provision of healthcare services, both the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have recently released comments on proposed telehealth regulations in Michigan and Delaware.

Michigan

On November 29, in response to requests from Michigan lawmakers to provide an opinion on the potential competitive impact of Michigan Senate Bill 753 (H-1), the DOJ released a statement describing how the Bill has the potential to enhance competition and promote greater use of telehealth services for the benefit of patients and consumers.

Michigan law already permits the provision of telemedicine services by licensed or authorized healthcare professionals. The Bill loosens restrictions in several ways:

- Broadening the scope of services to which the law applies to “telehealth,” which includes not only direct clinical services, but also the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support or promote long-distance clinical healthcare, patient and professional health-related education, public health, or health administration;

- Loosening consent regulations by permitting a health professional to directly or indirectly obtain consent required from patients for treatment provided through telehealth; and

- Allowing health professionals to prescribe drugs through telehealth if they are authorized to prescribe drugs in person and so long as the prescribed drug is not a controlled substance.

The DOJ observed that the Bill appropriately appeared to balance consumer safety and welfare with competitive benefits. In particular, the DOJ noted that making telehealth services more available will improve the convenience and affordability of healthcare, potentially encouraging patients to seek out care sooner or obtain care faster and saving patients unnecessary in-person visits.

Delaware

Also on November 29, in response to a request for public comments from the Delaware Board of Speech/Language Pathologists, Audiologists and Hearing Aid Dispensers, the FTC submitted comments on a proposed regulation to allow telepractice in those fields. In this case, the FTC identified areas in which the proposed regulation may be unduly restrictive and encouraged the Board to consider changes.

The Board proposes to eliminate an existing regulation that does not allow licensed speech/language pathologists, audiologists and hearing aid dispensers to evaluate or treat clients solely by “correspondence,” which includes telecommunication. The proposed regulation permits “the application of telecommunications technology to the delivery of speech/language pathology, audiology and hearing aid dispensing professional services at a distance,” but imposes certain requirements. In particular, the Board proposes that all initial evaluations must be performed face to face, and not through telepractice.

The FTC is predictably enthusiastic about the relaxation of prohibitions on telepractice, noting that the proposed regulation likely would encourage the delivery of speech/language and audiology services by telepractice, thereby increasing competition, consumer choice, and access to care. The FTC raises the concern, however, that the proposed limitation of telepractice to “interventions and consultations” and requiring all initial evaluations to be performed in person effectively prohibits some telepractice diagnostic services and may discourage practitioners and consumers from using telepractice for post-evaluation treatment or intervention. The FTC cites with approval laws, regulations and policies in 16 states and the District of Columbia that do not require in-person initial evaluation or contact, as well as telehealth regulations in several other specialties. The FTC recommends that the Board consider avoiding a blanket restriction on initial evaluations by allowing licensed practitioners to make the determination as to whether telepractice is appropriate for an initial evaluation.

Conclusion

Both the FTC and DOJ have endorsed the introduction of innovative, competing models for delivering and promoting healthcare, such as telehealth, as having the potential to improve access to care, contain costs, and encourage more ways to deliver needed care. The agencies appropriately focus on identifying and reducing or eliminating barriers and regulatory burdens that may stand in the way of such developments, asking regulators to consider the benefits of competition and adopt a flexible approach to restrictions that are aimed to address health and safety concerns.

California’s $20 Billion Problem: The Staggering Cost of Obamacare Repeal Threatens Health Coverage for Over Four Million Californians

By Tom McMorrow, Partner, Government and Regulatory | Steve Coony, Managing Director, Government and Regulatory | Delilah Clay, Legislative and Regulatory Advisor, Government and Regulatory

The repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) could ultimately cost California as much as $20 billion in annual federal spending on the state’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal. Putting this in perspective, $20 billion represents nearly 18% of all state General Fund spending, projected at $113 billion this year. A total of $20 billion is also roughly what the state already pays from its own general fund for Medi-Cal costs. (NOTE: The figures used in this article were provided by the California Department of Finance.)

Replacing a $20 billion deficit in healthcare spending with state funds alone would require California to either raise new taxes or reduce spending significantly, or both.

Raising the state income tax to cover a $20 billion shortfall would require nearly a 25% increase. This increase would be in addition to Californians’ November vote to raise their own taxes by a projected $8 billion, nearly half of which are to pay state healthcare costs.

Reducing the number of Californians insured under the ACA to address a $20 billion cut in federal ACA funding would require cutting off health coverage to nearly four million individuals insured under Medi-Cal or the state’s private health benefits exchange, Covered California.

Repeal of the ACA presents a greater risk to California than to any other state, not only because its population represents more than 10% of the nation’s total, but because the state fully embraced the promise of the ACA with strong bipartisan support from both Governor Jerry Brown and his predecessor, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, as well as the legislature. The ACA offered states significant federal incentives if they chose to expand healthcare coverage for previously uninsured residents, using a combination of increased eligibility thresholds for Medicaid (previously 100% of poverty level, now up to 138%) and federal subsidies for individuals who purchased healthcare plans through California’s health exchange. Of the 32 states that adopted Medicaid expansion, California covered more of its previously uninsured than any other state by far.

Congressional Republican plans to repeal and replace the ACA over the years have centered on rolling back the Medicaid eligibility expansion, subsidizing payments for insurance through health benefit exchanges, and/or fundamentally altering the current state and federal shared funding responsibilities within Medicaid through the use of capped or constrained-growth federal block grants to the states. Early estimates of the impact for California indicate that block grant funding, as proposed by House Speaker Paul Ryan, could result in a 26% or $14.3 billion cut in federal spending supporting Medi-Cal.

Rolling back eligibility instead for the nearly three million Californians who gained Medi-Cal coverage under the ACA would result in the loss of over $15 billion a year in federal funding. The potential loss of federal subsidies to the estimated 1.4 million individuals who now purchase health coverage through Covered California amounts to more than $5 billion a year. Combining either capped block grant funding or rollback of expansion with elimination of Covered California subsidies totals $20 billion. Combining all three proposals could put the total lost federal support to California at over $20 billion.

There have been many scenarios floated publicly to date by President-elect Trump’s transition team and the congressional Republican leadership as to how to repeal and replace the ACA. One common denominator is that the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid coverage will be rolled back in some form, all but ensuring a significant increase in the number of uninsured Californians, barring a successful state effort to pay its own way to cover the resulting uninsured.

California’s legislative leaders have vowed to fight repeal and to step in to ensure that any resulting federal funding gaps to the state will not move millions of Californians from being insured to uninsured.

The legislative leaders’ pledge presents an unprecedented challenge. Prior to the ACA, California was home to the nation’s highest uninsured population at around 6.5 million in 2013. Since that time, California’s uninsured population dropped by nearly half, down to 3.3 million in 2015. How the state is to come up with as much as $20 billion a year to maintain ACA-like coverage for the recently insured may be the greatest test for California’s newly sworn-in 2017-2018 legislature.

California Court Expands Roadmap for “Reasonable Value” of Providers’ Services

By Luke Punnakanta, Associate, Litigation

Health plans generally are obligated to pay out-of-network providers only the “reasonable value” of their services and not their full billed charges, which often are higher. Therefore, disputes over what constitutes the reasonable value of a provider’s services are common in reimbursement litigation between out-of-network providers and health plans. Parties to these lawsuits often spend much time gathering evidence regarding providers’ rates and later litigating what evidence is most relevant. A recent California Court of Appeal opinion, Moore v. Mercer, 4 Cal. App. 5th 424 (2016), from a different context suggests the types of discovery and motion practice regarding “reasonable value” evidence that litigators should keep in mind.

Evidence of Reasonable Value

Courts consider a wide variety of evidence when deciding the reasonable value of a provider’s services. Relevant evidence might include rates charged by other nearby providers for the same services, the rate Medicare would pay for the services, rates accepted by the provider in the past for the same services, and/or rates at which the provider has contracted with other parties. See Children’s Hosp. Cent. California v. Blue Cross of California, 226 Cal. App. 4th 1260 (2014). Litigating parties often conduct discovery to obtain evidence showing these various rates, and trial often focuses on which types of rates best match the health plan’s reimbursement obligation.

Moore v. Mercer

In Moore, Ms. Moore was injured in a car accident that was the other driver’s fault. Later, Moore sought back surgery to cure pain caused by the accident. Moore, who had no health insurance, signed a medical lien document with the surgeon before the procedure, agreeing to pay the surgeon’s full billed charges. The surgeon later sold the account receivable and lien at a discounted rate to a medical finance company for approximately 50 cents on the dollar.

Moore eventually sued the other driver, seeking, among other damages, the reasonable value of the medical services she received as a result of the car accident. The tortfeasor filed a motion to compel production of the agreement between the surgeon and the medical finance company, arguing the rate paid by the finance company was relevant to proving the reasonable value of the surgeon’s services. The trial court disagreed and denied the motion. Later, nearing trial, the court also granted Moore’s motion in limine, barring the tortfeasor from introducing any evidence concerning the amount the surgeon had discounted the bill to the finance company. Following trial, at which Moore prevailed, the tortfeasor appealed.

The Court of Appeal addressed three issues. First, the Court distinguished cases holding that tort victims may not recover more in damages for medical costs than the amount their insurer had contracted with the provider to pay for the services, because those tort victims were never responsible for paying full billed charges. Moore’s responsibility, on the other hand, was not limited to the amount the medical finance company paid to acquire the surgeon’s account receivable; according to evidence, she remained fully liable, and therefore she could recover the reasonable value of the surgeon’s services.