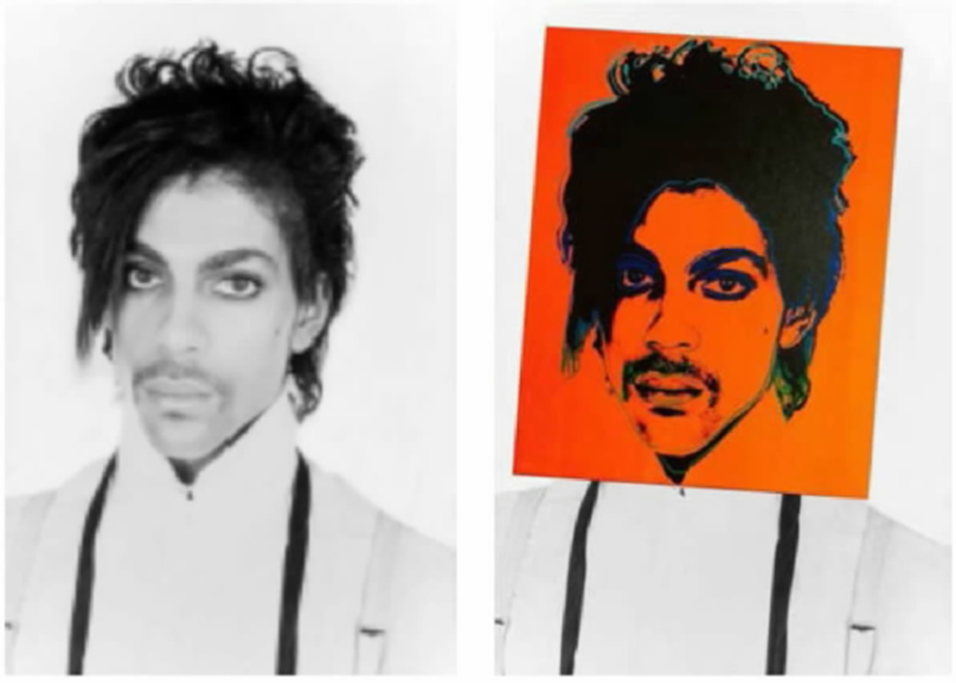

In Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith,1 the Supreme Court held, in a 7-2 decision, that the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) infringed photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright when it sold the right to use one of Andy Warhol’s images of Prince to Condé Nast without authorization from Goldsmith. The Court held that fair use “is an objective inquiry into what a user does with an original work, not an inquiry into the subjective intent of the user, or into the meaning or impression that an art critic or judge draws from a work,”2 and it found that Warhol’s work had the same commercial purpose as the original photo, so it was not a fair use.

AWF argued that Warhol’s artworks were transformative of Goldsmith’s photo because the artist gave new meaning to the original Prince photograph. The Court was not convinced, observing that the transformative character of the work was not dispositive on its own. Rather, the Court held that AWF’s licensing of Warhol’s work to Condé Nast did not have a sufficiently different purpose from the photo taken by Goldsmith because both portraits of Prince were used in magazines for articles about Prince.3

Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, filed an opinion concurring with the majority, clarifying that courts should not “speculate about the purpose an artist may have in mind when working on a particular project.” Instead, courts must only determine the purpose and character of the later use of an original work. Gorsuch explained that the decision was limited to interpreting this one factor of fair use, i.e., “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” under 17 U.S.C. § 107(1). Gorsuch left open the possibility that users of the Prince images could claim fair-use protection in other situations, for example, if AWF wanted to display Warhol’s image of Prince in a nonprofit museum or a for-profit book commenting on 20th-century art.4

Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, dissented, arguing that the majority holding will prevent creativity of every type and inhibit the creation of new art, music and literature. Kagan also criticized the majority’s lack of appreciation of how Warhol’s work differed from the photo taken by Goldsmith, and she noted that the Court had recently referred to Warhol’s paintings in dicta as a perfect example of a transformative fair use.5

Practical Implications

The Court’s decision has strengthened the protection of copyrights for a commercial purpose by holding that it may not be enough to claim that a work offers a new expression of a prior work to receive fair-use treatment. Rather, under the first factor, to be exempt from copyright infringement because of fair use, the purpose or character of the use in the new work must differ from the commercial use of the original work. This decision will likely impose new obligations on follow-on works by others, increasing the need to obtain a license before selling such works. The ruling could affect copyrights on music, videos and books, as well as Warhol’s other works. However, as indicated by the concurrence, the majority opinion would seemingly be limited to commercial use follow-on works, and other types of uses might be allowable.

Irah Donner is a partner in Manatt’s Intellectual Property practice and is the author of Patent Prosecution: Law, Practice, and Procedure, Eleventh Edition, and Constructing and Deconstructing Patents, Second Edition, both published by Bloomberg Law.

Figure – Warhol’s orange silkscreen portrait of Prince superimposed on Goldsmith’s portrait photograph.

1 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 143 S.Ct. 1258, 2023 USPQ2d 603 (2023).

2 Id., 143 S.Ct. at 1284.

3 Id., 143 S.Ct. at 1284-85.

4 Id., 143 S.Ct. at 1289-90 (Gorsuch, J., concurring).

5 Id., 143 S.Ct. at 1312 (Kagan, J., dissenting).