Connecting Justice-Involved Populations to Health Coverage and Care

By Kinda Serafi, Counsel, Manatt Health | Jocelyn A. Guyer, Managing Director, Manatt Health | Christopher Cantrell, Manager, Manatt Health

Editor’s Note: The importance of connecting justice-involved populations to health coverage and care is evident from the high levels of physical and behavioral health issues they experience. People in prisons have four times the rate of active tuberculosis found in the general population, nine to ten times the rate of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, three times the rate of serious mental illness and four times the rate of substance abuse disorders.

In a new policy guide, summarized below, Manatt Health and The Urban Institute provide a road map for state and local justice and healthcare officials and other stakeholders to improve health coverage and outcomes for justice-involved people, enhance public safety, reduce recidivism, and more efficiently use public resources. The guide provides a menu of options, including real-world examples, that states and localities may consider for meeting the challenge of connecting justice-involved populations to health coverage and coordinated systems of care. Click here to download a free copy of the full policy guide.

_____________________________________________________

The Importance of Connecting Justice-Involved Populations to Health Coverage and Care

Although the Constitution requires states and localities to provide healthcare to people in prisons and jails, many still fail to receive needed care. When individuals are released from those institutions, they often face disruptions in medical care that contribute to recidivism, drug use, and poor and costly health outcomes. Further, there is a particular nexus between behavioral health and reoffending, with people returning from prison with mental health conditions and substance abuse problems reporting higher levels of criminal behavior.

There is emerging evidence that connecting justice-involved people to health coverage and care in the community can increase rates of behavioral health treatment, as well as levels of well-being and health for re-entering populations. If states and localities can facilitate such linkages, they will be in a stronger position to address substance abuse issues, chronic physical and mental illness, unemployment and employment stability, and homelessness that result in many individuals cycling in and out of justice settings or hospitals.

Opportunities and Challenges

The Medicaid program presents manifold opportunities to improve poor health outcomes for people re-entering the community. The rules surrounding when services rendered to justice-involved people may be reimbursed by Medicaid, however, are complex and vary from state to state. Key federal requirements and options include the following:

- Federal rules prohibit Medicaid from paying for medical services and prescription medications for people while they are incarcerated, except when inpatient or institutional services are provided in a community-based setting, such as if someone serving a jail term must be hospitalized outside the jail for care.

- People who meet Medicaid eligibility requirements may be determined eligible for Medicaid before, during and after their incarceration as long as the state does not use federal Medicaid dollars for their healthcare services while they are incarcerated.

- Medicaid enrollment can be suspended upon incarceration and reactivated upon release.

- Medicaid federal administrative funding is available to support the development and operation of eligibility and enrollment functions to serve the justice-involved population.

Strategies for Connecting Justice-Involved Populations to Health Coverage and Care

Strategies that states and localities may consider for connecting justice-involved populations to health coverage and care can be organized around three areas:

- Enrolling the justice-involved population in Medicaid;

- Fostering linkages to coordinated, comprehensive healthcare that meets the distinctive needs of the justice-involved population; and

- Identifying financing options for enrollment and delivery system initiatives for justice-involved populations.

These strategies can be adopted alone or in combination to meet the unique needs of a state or locality. Though the strategies focus on incarcerated or re-entry populations, many are applicable throughout the justice continuum, including from arrest through pretrial and community supervision through alternatives to incarceration. Some strategies require collaboration and regular communications between the state Medicaid agency, state and local criminal justice agencies, and perhaps local health agencies. They also may require state Medicaid agencies to seek federal administrative funding and identify a source of nonfederal matching dollars.

1. Enrolling the Justice-Involved Population in Medicaid

Strategies for enrolling the justice-involved population in Medicaid fall into three areas:

First, bolster the eligibility and enrollment workforce. These strategies seek to increase the capacity of state and local eligibility and enrollment workers to help justice-involved populations enroll in and retain coverage. They include:

- Leveraging existing enrollment staff—including community-based navigators, application assisters and eligibility workers—to conduct outreach and enrollment for justice-involved people

- Establishing a special populations enrollment unit (or expanding an existing unit) within the state’s Medicaid agency to address the unique challenges and systemic issues for justice-involved people, such as identity proofing and the need for highly expedited application processing to prevent interruptions in care

- Engaging existing justice agency medical, behavioral health, case management and social services vendors to conduct enrollment

- Training justice-involved peer assisters, so justice-involved people can connect with knowledgeable and credible peers to increase their engagement in the enrollment process and their motivation to access needed care in the community

Second, set enrollment priorities. These strategies prioritize where to target outreach and enrollment efforts, as well as where to use information technology (IT) systems to efficiently identify those in need of coverage and trigger enrollment activity. Strategies include:

- Identifying incarcerated people with serious physical and behavioral health issues who are not yet Medicaid beneficiaries and prioritizing them for enrollment

- Establishing IT processes for checking Medicaid status to enroll uninsured people, including automated IT mechanisms for corrections and state Medicaid agencies to communicate with each other about a person’s incarceration and Medicaid coverage status

Third, improve suspension and renewal processes. Strategies in this category explore suspension and reclassification—alternatives to terminating Medicaid coverage for incarcerated individuals. Encouraged by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), improvements in suspension and reclassification are intended to ensure coverage is activated at the time of release and reserve Medicaid enrollment resources for people without prior coverage. Strategies to consider include:

- Establishing a process for state Medicaid agencies to suspend or reclassify Medicaid coverage status when a person becomes incarcerated and reinstate the enrollee’s full-benefit coverage upon release

- Renewing eligibility for incarcerated beneficiaries using available federal and state data

2. Fostering Links to Coordinated, Comprehensive Systems of Care

Although healthcare coverage is an important first step, it is not sufficient to ensure people receive the healthcare services they need. It is critical to have strategies in place that connect newly insured people to crucial healthcare services as they transition to the community. Strategies in this category fall into three areas:

First, enhance links to existing services and systems of care. These strategies focus on using the existing healthcare infrastructure to improve care for justice-involved people, focusing on encouraging health plans and providers to engage with people before they return to the community (known as “in-reach”). Strategies include:

- Amending state Medicaid agencies’ contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to support care coordination activities as enrolled people transition from jail or prison back to the community

- Assigning justice-involved people to an MCO before their release, increasing the effectiveness of in-reach in a Medicaid managed care environment

- Establishing routine and robust care transition processes as part of discharge planning, including a short summary of prescriptions, clinical summaries and treatment information that would be conveyed to community providers, if the re-entering person consents

Second, expand or create new coordinated, comprehensive systems of care. Strategies in this category focus on opportunities to increase coordination across agencies, health plans and providers and to promote comprehensive systems of coverage and care that address the specific health needs of justice-involved people. They include:

- Establishing health homes or health homes-like initiatives—integrated, team-based clinical approaches through which providers coordinate care for people with serious or multiple chronic conditions

- Creating a peer support program to assist people as they transition from jail back to the community

Third, increase access to critical Medicaid benefits. In this set of strategies, we look at opportunities to increase access to crucial medical benefits, such as medication and temporary respite, for people currently or formerly incarcerated. Strategies to consider include:

- Providing people being discharged with a 30-day supply of medication at release or a prescription to fill at a community-based pharmacy that accepts Medicaid reimbursement

- Requiring MCOs to provide Medicaid-allowable services for people returning to the community from incarceration, within specific timelines

3. Identifying Financing Strategies to Support Enrollment and Care

Our final set of strategies focuses on options for accessing Medicaid financing to support enrollment and care coordination for justice-involved populations in three categories:

First, fund enrollment assistance. The strategies in this category seek to leverage federal and state funding to support enrolling incarcerated people into Medicaid before they re-enter the community. Enrollment can involve either assisting uninsured incarcerated people in completing Medicaid applications or ensuring that, as soon as possible after release, standard coverage reactivates. Strategies include:

- Using Medicaid Administrative Claiming (MAC) to support prerelease enrollment efforts by public employees

- Partnering with MCOs or leveraging their capitation rates to fund re-enrollment

- Using the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) to support carve-out behavioral health plans or systems to enroll incarcerated people with mental health or substance use disorders

- Leveraging Medicaid or private grant funding sources for community-based organizations to support enrollment efforts in jails and prisons

Second, fund IT development. This section explores how state and local officials might claim 90% of federal Medicaid funding to support IT development that links the justice-involved population with a state Medicaid agency’s eligibility and enrollment system. Information technology links between previously disparate electronic systems serving Medicaid and justice agencies could streamline Medicaid enrollment and renewal processes for eligible, justice-involved, low-income youth and adults. Strategies include leveraging 90% MAC matching funds to help build an electronic interface between justice and Medicaid IT systems that supports Medicaid enrollment, eligibility status, adjustment and renewal.

Third, fund transition services. The strategies in this category suggest how state and local officials could tap federal funding for services that help incarcerated people transition toward receiving necessary care after community re-entry. Their objective is to facilitate the receipt of essential health services when justice-involved people return to their communities. Strategies include:

- Providing needed prescription drugs at discharge by giving departing people bottles of medicine; administering long-acting doses; or, when seeking Medicaid coverage for the medication, dispensing prescription drugs after people are free to leave but are briefly remaining on-site to obtain their medicine, so they are no longer considered incarcerated under Medicaid law

- Pursuing using administrative claiming for case management activities to fund transitional services that facilitate post-release care

Organizing for Action

Many of the policies above require collaboration and regular communication between the state Medicaid agency, state and local criminal justice agencies, and perhaps local health agencies. Each participating agency should consider designating a coordinator or contact person for interfacing with other agencies and quickly resolving problems. To monitor the target population and the success of selected initiatives, jurisdictions could also identify and attempt to collect performance measures when implementing the strategies. Finally, the strategies also may require state Medicaid agencies to seek federal administrative funding and identify the source of nonfederal matching dollars.

back to top

State Reinsurance Programs: 1332 Waiver Considerations for States

By Joel S. Ario, Managing Director, Manatt Health | Jessica B. Nysenbaum, Senior Manager, Manatt Health

Editor’s Note: In a new issue brief for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health and Value Strategies Program, summarized below, Manatt Health provides a road map of policy, program design and financing considerations for states contemplating the development of state-based reinsurance programs under 1332 waiver authority. Click here to download a free copy of the full issue brief.

_____________________________________________

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was designed in part to bring stability to the individual health insurance market. Faced with a fluid regulatory environment, however, many states continue to encounter challenges, including large premium increases and declining insurer participation.

One solution to continued market instability is a state-based reinsurance program similar to the federal program that reduced premiums by more than 10% per year from 2014 to 2016. State-based reinsurance programs offer substantial benefits, including reducing premiums, attracting insurers, limiting volatility, and leveraging the federal-state partnership to take advantage of federal matching funds.

The Trump administration has strongly encouraged states to establish their own reinsurance programs. In 2017, the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and the Department of the Treasury approved three 1332 state innovation waivers for reinsurance programs. These waivers offset program financing with federal “pass through” funding equal to the federal savings generated by reducing premiums. This means that to fund their reinsurance programs, states only have to cover the net cost after the federal pass-through funding is applied.

There are several bills pending in Congress that would provide reinsurance for all states in 2019. States wishing to control their own destinies, however, would be well-advised to proceed under current law, with contingency plans to take advantage of any new program that offers them a better deal than the current 1332 process.

Understanding the Potential Impact of a Reinsurance Program

Given variations both among and within states, assessing how reinsurance might help a specific state market starts with five questions:

- What market problem does it solve? Reinsurance can be a strong tool for problems around premium affordability, insurer withdrawals or excess volatility but does not help with issues such as network inadequacy and cost-sharing burdens.

- What is the average premium? States with higher-than-average premiums have more to gain from reinsurance, especially for unsubsidized enrollees paying full premiums.

- How much variation is there across rating areas? States with large regional variations may be hard-pressed to retain insurers in high-cost areas.

- What does current insurer participation in the market look like? Insurance regulators will want to consult past, present and prospective participants to understand what role reinsurance might play in their future participation.

- What is the profile of the state’s highest-cost enrollees? States may target specific high-cost conditions through a condition-based reinsurance program.

Designing a Reinsurance Program

After determining that reinsurance may be beneficial, states should turn to the next set of questions that help provide parameters around the scale and type of program that is the best fit:

- How large of a reinsurance program? States typically start with a premium reduction target of 5% to 20%, and then use actuarial modeling to determine the level of reinsurance financing needed to achieve that reduction. Next, they calculate how much of that financing will be offset by federal pass-through funding. Finally, they determine what level of state financing net of the federal offset is politically feasible.

- What type of reinsurance program? There are two broad types of programs, with many permutations. Condition-based models identify specific high-cost conditions to be included in the reinsurance program. Attachment point models focus on all claims, including accidents, and are based on each claim’s cost. (The attachment point is the point at which reinsurance starts to pay—with a cap at which the claim is no longer eligible for reinsurance.)

State Financing Considerations

Funding sources for a reinsurance program must be adequate and should include sources outside of the individual market. Without outside subsidization, reinsurance may help stabilize the individual market but will not reduce premiums.

1332 Waiver-Authorizing Legislation

Developing a strategy for legislative support and determining where this step fits into the timeline should be part of the early planning process. Federal law and guidance require state legislative authorization for both the waiver and the reinsurance program. The legislation must make the operation of the reinsurance program contingent on federal approval of the waiver.

Developing a 1332 Waiver Application

HHS has published a checklist that provides a step-by-step guide to what a state must include in its waiver application. Key areas of the waiver application include:

- Goals of the waiver—a description of how the reinsurance program will achieve the state’s objectives

- Authorizing legislation—a description of the state’s legislation authorizing both the 1332 waiver and the reinsurance program

- Funding—a description of the funding sources for the reinsurance program, the amount from each source and the estimated amount of pass-through funding

- Actuarial analysis—actuarial modeling, including a baseline scenario without the reinsurance program, and a year-by-year comparison of premiums and coverage with and without the reinsurance program

- Ten-year budget—an economic analysis, including a ten-year budget that considers all costs associated with the program

- Waiver development process—a list of public hearing dates and compliance with other public participation requirements

Planning the Waiver Timeline

State Health and Value Strategies has a “to-do” list for states considering a Section 1332 reinsurance waiver for plan year 2019. The first step is to sketch out a calendar of activities, which will vary depending on whether the state is a Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) or a State-Based Marketplace (SBM). The proposed due date for rate filings in FFM states is June 20, with SBM states having more flexibility in their submission timelines.

back to top

New Webinar: Redefining Care Management in Medicaid Managed Care

States are becoming increasingly demanding in their expectations of Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) when it comes to care management. Formerly a domain solely left to MCOs, many states are pushing health plans to move beyond a cubicle-and-telephonic approach, requiring new care management models that have the potential to change the way care is delivered. What does this mean for MCOs, providers and patients? How have these new requirements been reflected in state contracts with MCOs? What opportunities and challenges does this create for both small practices and provider-led organizations, such as Accountable Care Organizations and Clinically Integrated Networks?

Key topics include:

- An overview of evolving care management standards for MCOs across states

- Shifting state, plan and provider expectations around accountability, particularly for high-risk populations

- A discussion of how providers can position themselves to take on new care management opportunities—what’s in it for them, and what are the risks?

- Observations for the future, including the blurring of roles, states’ evolving view of where care management functions should be performed, and opportunities arising for all entities to rethink their roles and develop new models

Presenters:

Benjamin K. Chu, MD, Managing Director, Manatt Health

Melinda Dutton, Partner, Manatt Health

Sharon Woda, Managing Director, Manatt Health

Edith Coakley Stowe, Senior Manager, Manatt Health

back to top

Medicare Opioid Prescribing Rates Vary Widely Across the U.S.

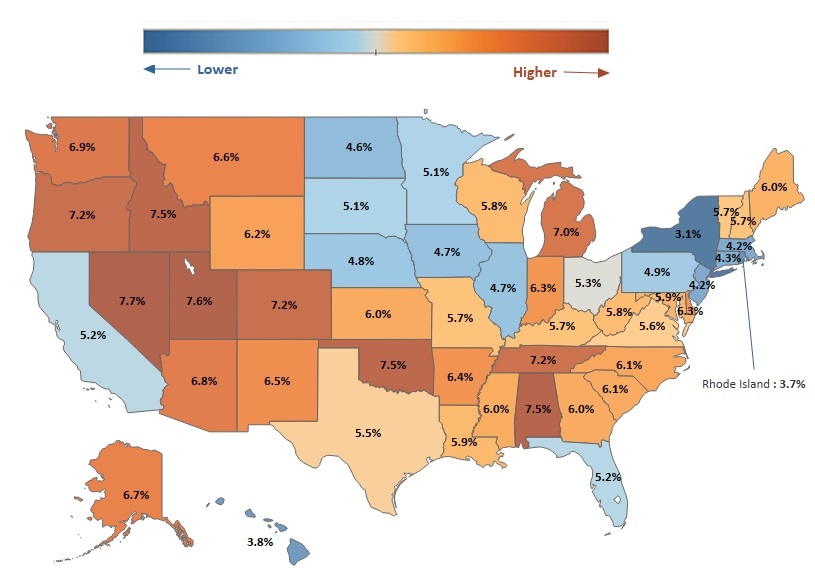

In 2016, 11.5 million people in the United States misused prescription opioids, and more than 42,000 people died from an opioid overdose. One factor in the opioid epidemic is the frequency with which providers prescribe opioids over other potential pain management options.

The Medicare opioid prescribing rate (portion of all Medicare prescriptions that are for opioids) varies noticeably across the lower 48 states, potentially reflecting different treatment norms or state policies on opioids. In 2015, the prescribing rate in New York (3.1%) was less than half the rate in Nevada (7.7%). Nationally, the opioid prescribing rate has trended downward since 2013. For example, Nevada’s 2015 rate of 7.7% reflects a 0.4% decrease since 2013, when the rate was 8.1% (not displayed).

Note: Analysis conducted by Dhaval Patel, senior manager at Manatt Health.

Source: Manatt Health analysis of Part D Prescriber Summary Table accessed February 2018, at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber.html

back to top

Mental Health and Minors: Proceed With Caution!

By Carri Becker Maas, Partner, Healthcare Litigation | John M. LeBlanc, Partner, Healthcare Litigation

Imagine representing a party in a lawsuit concerning coverage for mental health services. The lawsuit was brought by the parents of a minor child. The client received a request for production of medical records concerning the child’s mental health treatment. Can the client produce the records?

In short: it depends.

The path to the correct answer is exceedingly complex. It requires an analysis of federal privacy rules, state privacy and minor consent laws, and applicable regulations. This article provides an overview of the type of analyses a lawyer should undertake to determine whether a minor’s medical records relating to mental health treatment may be produced.

HIPAA Privacy Rules

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) establishes federally protected rights that permit individuals to control certain uses and disclosures of their protected health information, including their medical records.

Under HIPAA Privacy Rules, with certain exceptions, mental health records are generally treated the same as medical records. In the context of litigation, medical records can typically be disclosed by a covered entity (defined as providers, health plans and other entities specified under 45 C.F.R. 160.103) in any one of the following situations:

a) The patient provides written permission for the disclosure;

b) The covered entity is a party to the litigation and uses or discloses the records for purposes of the litigation, so long as the entity makes reasonable efforts to limit such uses and disclosures to the minimum necessary to accomplish the intended purpose;

c) The covered entity receives a court order; or

d) The covered entity receives a subpoena for the information, if the covered entity either:

i. Notifies the subject of the information about the request, so the person has a chance to object to the disclosure; or

ii. Seeks a qualified protective order from the court.

See 45 C.F.R. § 164.512(e).

Yet HIPAA Privacy Rules alone do not answer the question as to when and under what circumstances a minor’s mental health records may be disclosed. State privacy laws and state laws concerning consent and minors must also be considered.

State Privacy Laws

Many states have enacted privacy laws that are more stringent than HIPAA and place further protections on disclosure of medical records generally and mental health records specifically.

In California, mental health records may be subject to one of two state laws: (1) the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, California Welfare and Institutions Code, Section 5328 et seq. (LPS Act); or (2) the California Confidentiality of Medical Information Act, California Civil Code Section 56 et seq. (CMIA). To determine whether mental health records may be disclosed under California law, the first inquiry to make is whether the records are subject to the LPS Act or CMIA.

The LPS Act concerns involuntary civil commitment to a mental health institution in the state of California, and it strictly prohibits the disclosure of medical records concerning involuntary commitments absent a court order. Cal. Welf. & Inst. Code § 5328(f). In contrast, the CMIA generally prohibits a healthcare provider, healthcare service plan or contractor from disclosing medical information regarding a patient without first obtaining a written authorization from the patient, with certain exceptions. Cal. Civ. Code § 56.10. Disclosures can be made without written authorization in certain circumstances, including but not limited to where compelled by:

- Court order;

- An administrative agency under its lawful authority; or

- A party to a legal proceeding before a court or administrative agency by subpoena or other authorized discovery mechanism.

Cal. Civ. Code § 56.10.

Even if applicable state laws authorize disclosure of mental health records, that is unlikely to be the end of the inquiry where a minor’s medical records are involved.

Consent and Minors

When consent to release a minor’s records is required under federal or state law, who is authorized to provide that consent?

Under the HIPAA Privacy Rule, “personal representatives” are those persons who have authority, under applicable law, to make healthcare decisions for a patient. Typically, a parent, guardian or other person acting in loco parentis (collectively, Parent) is considered a personal representative of his or her minor child. As such, he or she has the authority to make healthcare decisions for the minor and may exercise the minor’s rights with respect to protected health information.

But there are several important exceptions to this rule. A Parent is not considered the “personal representative” of his or her minor child when:

- A minor has consented to the healthcare services and the consent of the Parent is not required by federal or state law;

- Someone other than a Parent is authorized under federal or state law to provide consent for the medical services to a minor and provides such consent (e.g., court-ordered healthcare services); or

- A Parent consents to a confidential relationship between the minor and a healthcare provider with respect to the healthcare service.

In addition to these federal rules, many states have enacted more stringent privacy and informed-consent laws concerning minors. These laws generally fall into two categories: laws based on the status of the minor (e.g., minors who are emancipated) and laws based on the type of care sought (e.g., mental health or family planning).

For example, in California minors 12 years or older may consent to outpatient mental health treatment if, in the opinion of the treating provider, the minor is mature enough to participate intelligently in the mental health treatment. Cal. Health & Saf. Code § 124260. In such a case, a provider cannot share the minor’s medical records with his or her parents (or others) absent a signed authorization from the minor. Cal. Health & Saf. Code §§ 123110(a), 123115(a)(1); Cal. Civ. Code §§ 56.10, 56.11, 56.30.

Federal law also permits providers to refuse to produce medical records to a parent or person otherwise entitled to receive them if the provider believes that (a) the patient has been or may be subject to violence, abuse or neglect by that person; (b) the patient may be endangered if that person is treated as a personal representative; or (c) it is not in the best interests of the patient to treat the person as a personal representative. 45 C.F.R. § 164.502(g). California state laws similarly permit a provider to refuse to disclose records if the provider believes disclosure would negatively impact (a) the provider’s professional relationship with the minor or (b) the minor’s physical safety or psychological well-being. Cal. Health & Saf. Code § 123115(a)(2).

Records Subject to Heightened Protections

Another critical inquiry is whether the specific type of records requested may be disclosed under any circumstances. Certain classes of medical records are subject to heightened protections; two examples are psychotherapy notes and medical records regarding substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses and treatment.

1. Psychotherapy Notes

The HIPAA Privacy Rule distinguishes between mental health information that is contained within an individual’s medical record and psychotherapy notes. Psychotherapy notes are subject to heightened protections and, with limited exceptions, may be disclosed only if the patient signs an authorization permitting disclosure. See 45 C.F.R. § 164.508(a)(2). Similarly, a personal representative is precluded from obtaining psychotherapy notes regarding his or her minor child. Disclosure of psychotherapy notes is permitted only where certain federal exceptions apply, including where disclosure is required by law, such as mandatory reporting of abuse and duty to warn in cases of serious and imminent threats.

Even where disclosure is permitted under federal law, state laws should also be consulted. Where state laws conflict with federal laws, a pre-emption analysis will need to be undertaken to determine which law governs.

2. Substance Use Disorders

Another class of records afforded heightened protection relates to SUDs. The Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records regulation, 42 C.F.R. Part 2, applies to any individual or program that is federally assisted and holds itself out as providing, and provides, alcohol or drug abuse diagnosis, treatment or referral for treatment. This federal law restricts the disclosure and use of patient records that include information on substance use diagnoses or treatment information. 42 C.F.R.§ 2.11. Except in very limited circumstances, this law requires a patient’s written consent—with nine specified elements, including the precise recipient of the disclosed information and the purpose of the disclosure. 42 C.F.R. §§ 2.31(a), 2.51-2.53.

Where medical records contain SUD diagnoses or treatment information, disclosure should not be made absent specific written authorization from the patient—or the patient’s personal representative—unless an exception applies. See 42 C.F.R. §§ 2.51-2.53 (establishing exceptions for medical emergencies, research and audits).

Conclusion

Lawyers are well-advised to proceed with caution in the complex arena of mental health privacy laws, especially with regard to minors. While this article highlights some of the federal and state laws at play, a comprehensive review of all potentially applicable federal and state laws is strongly advised before disclosure in any case.

back to top

Now on Demand: Healthcare Litigation in a Transforming Environment

Click Here to Download a Free Copy of the Presentation.

In just the first year of the Trump administration, healthcare has faced an avalanche of change—from the proposed “conscience regulation” to tightening False Claims Act (FCA) scrutiny to new Medicaid work requirements. The disputes arising from the flood of new developments encompass both legal and regulatory challenges—and are being played out in both courts and government agencies. Ultimately, they may trigger significant shifts in existing healthcare law.

How will healthcare litigation be affected? What are the game-changing trends and cases to watch in 2018—and how could they remap the legal and regulatory landscapes? Manatt shared the answers in a recent webinar for Bloomberg BNA—and we want to be sure you don’t miss out on this important information. If you or anyone on your team were unable to attend the original program click here to download a free copy of the presentation, for your continued reference.

Key topics covered include:

- The latest insights into the Trump administration’s healthcare positions, policies and priorities—including what we’ve seen in the first year and what’s likely to come

- The major FCA cases transforming fraud and abuse litigation and the decisions to watch in the year ahead

- New guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for states seeking Section 1115 waivers that condition Medicaid eligibility on work and community engagement

- The issues around the proposed “conscience regulation,” as well as the new CMS guidance to Medicaid directors restoring state flexibility to decide program standards

- An update on the laws and litigation around discrimination on the basis of gender identity and termination of pregnancy

If you have any questions or issues you want to discuss after viewing the webinar, please reach out to our presenters:

- Ileana Hernandez, Partner, Litigation, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP, at 310.312.4116 or ihernandez@manatt.com

- Michael Kolber, Partner, Manatt Health, at 212.790.4510 or mkolber@manatt.com

- Craig Rutenberg, Partner, Litigation, Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP, at 310.312.4333 or crutenberg@manatt.com

back to top

The Risk Corridors Program: Should the Government Pay?

By John M. LeBlanc, Partner, Healthcare Litigation | Samuel A. Canales, Associate, Litigation

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established health insurance exchanges where insurers can offer qualified health plans (QHPs) to individuals and certain employers. Because the exchanges made coverage available to people who previously were uninsured or underinsured, some QHP issuers may have lacked enough information to properly evaluate risk and anticipate costs.

To encourage QHP issuers to set modest premiums during the early years of the exchanges, the ACA established a three-year risk corridors program (Program) that would reimburse QHP issuers certain excess benefit costs. However, by the end of the Program, the federal government had yet to reimburse QHP issuers more than $12 billion. The government has since refused to appropriate sufficient funds to pay the outstanding amounts. The article below provides a brief overview of the Program, two important cases on appeal concerning the federal government’s obligation to make the payments, and the recently passed omnibus spending bill.

The Risk Corridors Program

The Program started in 2014 and required QHP issuers to spend a certain portion of premium funds (target amount) on healthcare and quality improvement (allowable costs) each benefit year. See 42 U.S.C. § 18062. QHP issuers that spent less than 97% of the target amount had to pay a portion of their gains into the Program (Collected Amounts). 42 U.S.C. § 18062(b)(2); 45 C.F.R. § 153.510(c). QHP issuers that spent more than 103% of the target amount would be reimbursed a portion of their excess losses (Risk Corridors Payment). 42 U.S.C. § 18062(b)(1); 45 C.F.R. § 153.510(b).

Through annual appropriations riders, Congress limited funding for the Risk Corridors Payments to the Collected Amounts. Risk Corridors Payments exceeding the Collected Amounts were transferred to the following year. However, by the end of the Program in 2016, more than $12 billion remained outstanding due to QHP issuers experiencing more significant losses than significant gains, resulting in inadequate Collected Amounts. The government has since refused to appropriate additional funding to cover the outstanding Risk Corridors Payments, prompting many QHP issuers to file suit.

Legal Actions Concerning the Outstanding Risk Corridors Payments

Two important cases addressing the outstanding Risk Corridors Payments are Land of Lincoln Mutual Health Insurance Company v. United States and Moda Health Plan, Inc. v. United States.

In Land of Lincoln Mutual Health Insurance Company, Judge Charles Lettow of the Court of Federal Claims held that “HHS’s decision not to make full payments annually cannot be considered contrary to law.” Land of Lincoln Mut. Health Ins. Co. v. United States, 129 Fed. Cl. 81, 108 (2016). The court found that the ACA was “ambiguous in terms of the ‘payments in’ and ‘payments out’ arrangement for risk-corridors payments because it does not contain an express authorization for appropriations to make up any shortfall in the ‘payments in’ to cover all of the ‘payments out’ that may be due. And, it does not explicitly require ‘payments out’ to be made on an annual basis, whether in full or not.” Id. at 106. Because of these ambiguities, the court deferred to “HHS’s interpretation [of the ACA, which] was reflected in its final rule on May 27, 2014, [where] it stated that it intended to administer risk corridors in a budget neutral way over the three-year life of the program, rather than annually.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). The court also found there was no contract between Land of Lincoln Mutual Health and the government concerning the Program. Id. at 108-113.

In contrast, in Moda Health Plan, Inc., Judge Thomas Wheeler of the Court of Federal Claims held that “the Government . . . unlawfully withheld risk corridors payments from Moda, and is therefore liable. The Court [found] that the ACA requires annual payments to insurers and that Congress did not design the risk corridors program to be budget-neutral. The Government is therefore liable for Moda’s full risk corridors payments under the ACA. In the alternative, the Court [found] that the ACA constituted an offer for a unilateral contract, and Moda accepted this offer by offering qualified health plans on the Health Benefit Exchanges.” Moda Health Plan, Inc. v. United States, 130 Fed. Cl. 436, 441 (2017). The “Government made a promise in the risk corridors program that it has yet to fulfill. [T]he Court [directed] the Government to fulfill that promise. After all, to say to [Moda], ‘The joke is on you. You shouldn’t have trusted us,’ is hardly worthy of our great government.” Id. at 466 (quoting Brandt v. Hickel, 427 F.2d 53, 57 (1970)).

Both cases are on appeal in the Federal Circuit, which heard oral argument in January 2018.

The Health & Human Services 2019 Budget

In an interesting turn of events, the Health & Human Services (HHS) 2019 proposed budget released on February 12, 2018, included $11.5 billion to fund the outstanding Risk Corridors Payments. Land of Lincoln Mutual Health Insurance Company and Moda Health Plan, Inc. alerted the Federal Circuit to the budget, and argued that it showed the federal government’s intent to fund the Program. However, on February 19, 2018, HHS posted a revised budget once again limiting outlays for the Program to the Collected Amounts. On March 23, 2018, President Trump signed into law a $1.3 trillion omnibus spending bill that did not appropriate additional funds to cover the outstanding Risk Corridors Payments.

Conclusion

In light of the federal government’s steadfast refusal to fully fund the Program, the Federal Circuit’s decisions in Land of Lincoln Mutual Health Insurance Company and Moda Health Plan, Inc. will have significant financial consequences in these cases and the numerous others just like them. The Federal Circuit’s decisions are expected any day now.

back to top

How Can All-Payer Claims Databases Support Insurance Regulation?

By Joel S. Ario, Managing Director, Manatt Health | Kevin McAvey, Senior Manager, Manatt Health

Editor’s Note: On March 24, 2018, Joel Ario, managing director at Manatt Health, and Kathy Hempstead, a senior advisor to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, delivered a presentation on All-Payer Claims Databases (APCDs) to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Regulatory Framework Task Force. The presentation, summarized below, provided a detailed look at APCDs, including use cases and caveats. Sharing preliminary considerations, the presentation was the product of extensive research and nearly a dozen interviews with state APCD and insurance leaders. Click here to download the full presentation free.

The final presentation and report will be delivered at the next national NAIC meeting in August.

________________________________________

What Are APCDs?

All-Payer Claims Databases (APCDs) are centralized state data repositories for health insurance membership and claims records. States with APCDs typically require insurers operating in their markets to regularly submit medical, pharmacy and dental claim files for all members residing in and/or contracted in their state. Mature APCDs allow for cross-payer, marketwide enrollment, utilization and payment trend analyses and are an increasingly leveraged data resource by regulators, policymakers and researchers.

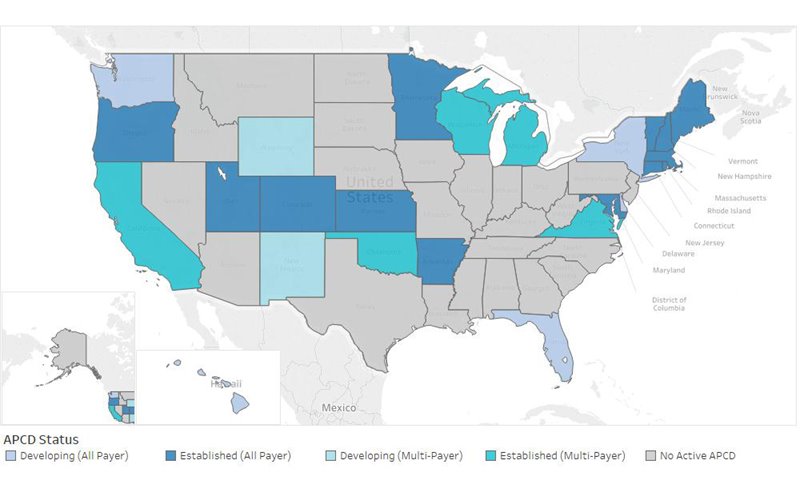

Maine was the first state to establish an APCD in 2003, and since that time, more than a dozen other states have either followed suit or are in the process of doing so. (Note: As shown on the map below, additional states have established voluntary “multi-payer” or partial APCDs.)

According to results of Manatt Health’s first APCD Capacity Survey—co-administered with the National Association of Health Data Organizations—on average, APCDs include data for three-fifths of their states’ populations, with robust coverage of the private fully insured, Medicaid and even Medicare Advantage populations. This breadth and depth of coverage make APCDs a particularly attractive data resource for insurance departments.

Source: Manatt Health APCD Catalogue (accessed March 1, 2018)

Four APCD Use Cases for Insurance Regulators

Mature APCDs have the potential to inform insurance department policy and program goals across four areas:

- Price Transparency: APCDs can provide a wealth of dynamic price data to inform the decisions of regulators, policymakers and even consumers. New Hampshire, Maine and Maryland, for example, have used data from their respective APCDs to populate consumer websites, where prospective patients can compare estimated costs for procedures and services across providers. Frequently complementing insurer-developed, plan-specific patient cost calculators, state consumer websites are often part of broader strategies to promote consumer empowerment and market competition. Other states have leveraged their APCDs to produce statewide cost-driver reporting and to identify, investigate, and respond to unexplained price variations between payers, providers and services.

- Rate Review: APCDs include data that insurance regulators can use to enhance their understanding of insurance markets for rate review purposes. Mature APCDs have the potential to generate useful trend reports on most claims categories of interest to insurance regulators, highlighting member experience differences by geography, demographic characteristics and time period. Mature APCDs also can allow for impact monitoring of delivery system reforms, quality initiatives and other ad hoc analyses (e.g., frequency and severity of claims for 1332 waiver reinsurance program proposals). The Maryland Insurance Administration uses its state’s APCD, the MD Medical Care Database, for example, to check payer submissions and run deeper analyses. Oregon’s Department of Consumer and Business Services uses its APCD (APAC) data in its review of premiums for individual and small group health plans, while Massachusetts’ Center for Health Information and Analysis has worked in partnership with its Division of Insurance to reduce the statewide payer reporting burden by directly sourcing several insurance reports from its APCD (supporting “administrative simplification”).

- Network Adequacy: APCDs have the potential to be a significant resource in helping insurance regulators set and monitor network adequacy standards. The New Hampshire Insurance Department, for example, views its APCD, the New Hampshire Comprehensive Healthcare Information System (CHIS), as a prime resource to help it monitor the impact of its new network adequacy regulation (IR 2701), which measures adequacy by service category rather than provider type. Mature APCDs have the potential to help insurance regulators answer critical questions about payers’ networks, including: Which providers deliver what services? Where are certain services scarce? And how much do prices differ between in- and out-of-network services by plan?1 APCDs may also be able to help inform specific policy questions, such as the prevalence of out-of-network charges at in-network facilities (i.e., surprise billing).

- Responding to the Opioid Crisis: APCDs have helped states to monitor and develop strategies for combating public health crises, including the opioid epidemic. APCDs can provide information on prescribing patterns at regional and physician levels, as well as the availability of treatment (e.g., medication-assisted treatment (MAT), naloxone or residential programs). APCDs also allow states to look at an issue in the broader context of how substance use disorders change over time as drug availability changes. Massachusetts’ APCD served as the data-backbone of the state’s new “Promote Prevent” plan to promote mental, emotional and behavioral health. The Massachusetts APCD was linked to more than a dozen other health and social service data sets to provide policymakers with a comprehensive depiction of the Commonwealth’s most vulnerable populations and potential root causes (e.g., access) for their behavioral health issues. Virginia’s APCD was similarly used to identify trends in opioid prescription volume, refills and dispensing habits, while Colorado’s APCD was used to identify prescription fill anomalies by matching drug users with reported clinical conditions.

APCD Cautions

While APCDs have the potential to substantively inform numerous insurance agency programs and priorities, most APCDs nationally are not yet mature enough and/or do not have the staff capacity that would allow for simple report request fulfillment. When approaching interagency collaboration, it is essential for insurance leadership to keep the following considerations in mind:

- Long-Term Partnership: Work with APCD agencies should be viewed as part of a long-term partnership, ideally fueled by small, shorter-term goals (and, hopefully, “wins”). Insurance and APCD leadership should work together to develop realistic goals and milestones jointly. (Also, keep in mind, the more APCDs are used, the more valuable they become: Use is the best data quality check, and it establishes foundational agency functions, processes and knowledge that will better support efficiencies in future collaborative efforts.)

- Communications: APCD and insurance department staff may not always speak the same language. For example, when referring to “membership,” one agency’s staff may intend to convey “a member months average for state residents”; another, however, may interpret “a point-in-time count by state situs.” Developing clear, shared business specifications is foundational to any successful project partnership. Business specifications are the road map by which technical specifications (i.e., programming logic and code) will be developed.

- Completeness, Timeliness and Accuracy: Though APCDs are significant data assets, they are not always the best data assets to answer every question. Depending upon the state and use case, APCDs may not have data that is relevant (e.g., clinical records), timely enough (e.g., claims lag) or complete enough (e.g., payer data submission anomalies) for use. Further, depending upon the “hosting agency” for a given APCD, various APCD data fields may have been emphasized for integrity. For example, when APCDs are hosted within Medicaid or health departments, critical foundational fields for insurance use—such as Situs or License Type—may not be as thoroughly tested and vetted as others, such as diagnosis codes (also important). Regardless of whether there is an imminent opportunity for APCD agency collaboration, insurance departments should be active and engaged stakeholders in their continuing development.

- Staffing (and Funding): APCD agencies are financially lean, with limited staff. Clearly delineating project roles, timelines and committed resource needs for any collaboration is an important step, as is identifying where external counsel would be critical (i.e., don’t reinvent the wheel). Joint agency collaborations may also be able to identify and leverage additional state and federal funding, especially where new funds may be available to address public priorities (e.g., opioids) or where long-term value propositions can be presented (e.g., administrative simplification).

APCDs can be—and are already, for some state insurance departments—tremendous and dynamic data assets. Their value will only continue to increase as use improves data quality and uncovers new use cases.

1Where in-network APCD flag is available and tested

back to top

Physicians’ Employment Agreements Raise Antitrust Concerns

By Lisl J. Dunlop, Partner, Antitrust and Competition | Shoshana S. Speiser, Associate, Litigation

Earlier this month, a physician group sued a healthcare system in North Carolina state court, accusing it of monopolization by including overly restrictive covenants in physicians’ employment agreements, thereby preventing the physicians from leaving and practicing independently. This case serves as an important reminder of the antitrust risks inherent in common restrictive covenants contained in physician employment agreements.

Atrium Health (Atrium), a nonprofit hospital system and the largest system in the Charlotte area, has over 1,100 physicians on staff at its flagship hospital and over 2,500 physicians in its clinically integrated network. Mecklenburg Medical Group (MMG) is a physician group with over 90 doctors. Each MMG physician individually contracts with Atrium, so that physicians’ employment agreements are not all identical. On April 2, 2018, MMG sued Atrium for a declaration that noncompete and nonsolicitation provisions in its physicians’ employment agreements are void, invalid or unenforceable on the grounds that they are overly broad and violate public policy.

According to the complaint, MMG’s employment agreements contain noncompete provisions that broadly prohibit employed physicians from operating a medical office, clinic or outpatient treatment facility, or otherwise engaging in any practice of medicine, within a 15-mile radius of certain Atrium-owned or -controlled offices. MMG claimed that the provisions effectively prevent the physicians from performing specialty work in the Mecklenburg County area for 12 or 18 months, even if that work is distinct from the work they performed as employees of Atrium. For example, the noncompete provision allegedly prevents the physicians from working as nonphysician managers of a practice or from performing charity physician work in the area.

Most of the employment agreements also contain a nonsolicitation provision that bars physicians from contacting, communicating with or targeting persons to provide services. The provision also restricts physicians from soliciting any Atrium patients who reside in the relevant geographical area and have consulted with, been treated by or been cared for by the physicians within the 12-month period immediately preceding termination for a 12-month period. These provisions prevented any physicians departing from Atrium’s employment from notifying their patients of the change or inviting them to continue receiving services at the physicians’ new practices.

MMG alleged that Atrium unilaterally decided to change certain physician employment terms, including by lowering physician compensation, effective January 1, 2018, and then notified the physicians that if they refused to execute the new agreements, they would be terminated “for cause.” Therefore, refusal to sign the new agreements would trigger the noncompete provisions.

The same day that MMG sued Atrium, Atrium announced that it would allow Mecklenburg to break away and operate as a new, independent group. Mecklenburg sent a letter on April 4 seeking to settle the suit, but as of April 9, Mecklenburg reported that it had received only a one-sentence email from Atrium stating that it was reviewing the suit.

Takeaways

As we reported in our April 2017 article, Atrium also was sued by the Department of Justice over anti-steering clauses in its insurer contracts, and the case survived an initial attempt to dismiss. Both anti-steering clauses and restrictive covenants are relatively common and can have procompetitive justifications, as well as serve legitimate business needs. For example, restrictive covenants may serve to prevent rivals from gaining an unfair advantage from a company’s investments in training its employees.

Agreements that unfairly restrict employees’ ability to practice their trade and compete with their former employer, however, may come under antitrust scrutiny. While the court has yet to make a determination on the validity of the noncompete and nonsolicitation provisions and whether they in fact run afoul of the antitrust laws, the case serves as an important reminder of the antitrust risks inherent in these common contractual clauses when they are not narrowly tailored.

back to top

DSRIP Antitrust Considerations: The Case for a COPA

By Lisl J. Dunlop, Partner, Antitrust and Competition

Editor’s Note: On March 27, 2018, the author partnered with Christine White, vice president of legal affairs at Northwell Health, Inc., to present a webinar for the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA) entitled “DSRIP Antitrust Considerations: The Case for a COPA.” Highlights are summarized below.

____________________________________________

Under New York State law, providers who might otherwise be viewed as competitors can apply for a Certificate of Public Advantage (COPA) for certain collaborative arrangements. If approved, a COPA can confer immunity under state and federal antitrust law. The webinar explained the COPA background and reasons why parties participating in a Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Performing Provider System (PPS) might consider applying for COPAs. The deadline for applying for a DSRIP COPA has been extended to December 31, 2020.

Background to COPA Laws: Healthcare and Antitrust Policy Issues

According to the federal antitrust agencies, the antitrust laws are consistent with healthcare reform’s triple aim of 1) improving quality, 2) enhancing patient experience and access to care, and 3) reducing costs. The antitrust agencies believe that mergers and collaborations consolidate market power, which can lead to adverse effects on competition, a position supported by economic research showing that consolidation leads to higher prices.

The agencies stress that regulation is not an effective substitute for competition and that COPA laws granting antitrust immunity are unnecessary to encourage procompetitive provider collaborations. While the agencies have consistently opposed COPA laws, they have also explained that competition is not a panacea for all of the problems with American healthcare.

COPA laws authorize “cooperative agreements” among competing providers where it is shown that the agreements can improve quality, moderate cost increases, improve rural access and help keep smaller hospitals open. These laws seek to balance competition with regulation and provide that competition is just one issue to take into account. Very few COPAs actually have been applied for or issued until recently, and there has been minimal research conducted on whether COPAs actually achieve their purported benefits.

Antitrust Laws and Provider Collaborations

The federal antitrust laws generally prohibit 1) agreements that restrain trade, 2) monopolization and 3) mergers that substantially lessen competition. Each state also has its own antitrust act which generally mirrors the federal statutes. Most often, the antitrust agencies will assess healthcare collaborations under the rule of reason, recognizing the fundamentally procompetitive reasons for entering into these arrangements.

In the DSRIP context, there are a number of issues that could give rise to antitrust liability:

- Joint contracting could be viewed as price-fixing;

- Value-based contracting may increase exposure to potential price fixing or boycott claims from payers who are not shy about suing or complaining to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC);

- A PPS agreement that particular providers will serve particular patient segments or that particular specialties will be located at particular facilities and that competing facilities would not offer certain services could be viewed as market allocation;

- PPS providers coming together to provide services to a group of patients could be viewed as taking away the opportunity for competitors to service that group of patients, which could be viewed as monopolization or group boycott activity;

- Exclusive agreements can also violate the antitrust laws if they harm competition by restricting distribution channels or access to particular services or patients; and

- Sharing of competitive information on which parties act can also be anticompetitive.

Lawsuits could be brought by local providers not participating in the PPS, or complaints could lead to government investigations. Excluded competitors may be incentivized to sue because if they are successful, they could be entitled to treble damages and attorneys’ fees.

The New York DSRIP Program

The DSRIP program is a state-sponsored pilot program arising from the Federal Social Security Act § 1115. A state’s ability to participate in this waiver program is subject to the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS) approval. Section 1115 waivers permit states significant flexibility in how they deliver their Medicaid programs and allow states to direct supplemental payments to providers that also invest in delivery reform.

New York’s DSRIP program is a regulatory solution to the problem of high Medicaid spending and subpar quality. New York had the second-highest spending in the nation and was concerned about its rising costs, as well as quality issues. For example, New York was rated last in the nation for its overutilization of hospitals. DSRIP seeks to achieve health system transformation and a 25% reduction in avoidable hospital use over five years.

To accomplish these goals, DSRIP involves extensive data collection and reporting and requires every PPS to satisfy milestones for the creation of infrastructure, as well as for process and outcomes metrics and milestones. As a result, DSRIP brings providers together to share significant data and information. New York State, concerned about potential antitrust liability discouraging providers, encouraged providers to seek COPAs providing antitrust immunity for PPS activities to drive participation.

The New York COPA Law and Regulations

The New York COPA law expressly states that “the intent of the state is to supplant competition ... and to provide state action immunity under the state and federal antitrust laws.” This language would almost certainly pass muster as a clear articulation of a state policy to displace competition.

The second requirement for state action immunity is active supervision. The New York COPA law itself stresses that active supervision is required. Whether there is sufficient active supervision, however, depends on what the state actually does. There needs to be continuous monitoring and interaction for a COPA to be valid. Any challenge to the validity of a COPA would likely target active supervision. The regulations include specific provisions requiring active supervision throughout the process and the COPA’s life cycle and include the ability to modify or revoke the COPA. Whether there is active supervision ultimately will be a factual question.

The COPA review process requires the New York State Department of Health (DOH) to assess the COPA’s primary service area, as a proxy for the relevant market, and try to anticipate the benefits or disadvantages that may occur within that area. The review process allows DOH to consider factors other than competition, including whether the PPS will help preserve services for needy populations or whether it facilitates the implementation of payment methodologies designed to control unnecessary costs or utilization.

The Staten Island PPS COPA

Following the submission of several COPA applications, the FTC sent a letter to DOH expressing its views that COPAs are unnecessary and based on inaccurate presumptions about the antitrust laws and the value of competition, including in a letter directed to New York on April 22, 2015. According to the FTC, because the antitrust laws permit procompetitive collaborations, COPAs only serve to protect anticompetitive collaborations. Nonetheless, DOH granted a COPA to Staten Island in December 2016 after receiving this letter. Another COPA application is still pending.

While Staten Island’s final COPA was never published, DOH published an executive summary in connection with the proposed COPA. The executive summary explains that the COPA is valid through March 31, 2020, or termination of the PPS’s participation in DSRIP and that the COPA has no bearing outside of the PPS’s Medicaid activities in connection with DSRIP. Additionally, the COPA was proposed to be subject to certain conditions, including:

- Acknowledgment by the PPS that it will not invoke COPA or antitrust immunity for any purpose outside of Medicaid activities under DSRIP;

- Acknowledgment by the PPS that material changes may result in additional conditions or the COPA’s revocation; and

- Continued compliance with the PPS’s reporting requirements.

The executive summary also set forth the considerations in granting the COPA. One factor was substantial coverage, which benefits DSRIP because accomplishing delivery system reform requires covering a large portion of the market. This, however, presents a conflict with the FTC’s concerns, which arise due to the participants’ high combined market shares. One key way to reduce antitrust exposure when bringing providers together is to ensure that participation is nonexclusive to the entity. In the PPS, the participating providers are permitted to provide services outside of the PPS, which reduces concerns.

DOH’s analysis also addressed the procompetitive benefits and efficiencies of the COPA, including increased access to local services, care coordination and disease management services, clinical integration, and performance-based financial incentives. The analysis also noted that there was a potential for anticompetitive effects through spillover into the commercial market, but those concerns were mitigated through nonexclusivity of the provider network, active supervision, an internal monitoring program, and an antitrust compliance policy and program.

COPA Filing Considerations

The webinar panelists discussed the advantages of the COPA’s grant of antitrust immunity from both private and government antitrust actions. The panelists explained that the additional time and expense, including the filing of the actual application and increased reporting obligations, are not burdensome, because the COPA is based on the DSRIP application. Finally, the panelists stressed the importance of compliance with COPA conditions and the need for active state supervision to ensure a good basis for state action immunity should the COPA ever be challenged.

back to top